Is it time to start rethinking the meaning of value, asks Valentina Doorly, and what will it mean for the future of capitalism?

In ancient Rome, the Haruspices were appointed the difficult task of interpreting signs and foretelling what the future beheld. This practice had been adopted from the highly evolved and, allegedly telepathic, civilization of Etruscans, who inhabited Tuscany in 700 BC.

Since then, the art and science of preconising future developments and facts has never ceased to fascinate humans. If anticipating and debating what will come next had such a prominent role in ancient societies, think how pivotal this exercise should be in a society that changes at the speed of light and where entire industries, lifestyles and businesses are dislocated and replaced in between lunchtime and your evening exercise class.

There are only a handful of world think tanks that dedicate substantial resources and engage prominent futurists to incessantly work at pre-painting the vision of probable futures and their meaning for our lives. They sit in San Francisco, London, Copenhagen and Washington. They convene annually, and compare findings to come up with points of agreement. One point they currently all agree on is that we are standing on a swiftly shifting tectonic plate. Maybe now its time to put the thinking hat on?

CURRENT TRENDS

A most fascinating occurrence is how big changes and outstanding facts can, in fact, stand in front of us in their full magnitude without us noticing.

In his last book, The age of oversupply, Daniel Alpert delivers a compelling and accomplished picture of our current world scenario, cutting deep at the very bones that have formed the skeleton of our economic model.

This model has patiently evolved from the early contour of the mercantile economies in Europe of the late middle age, billowed steadily through cut break and mould processes in the following three centuries, emerged triumphant with the industrial revolution, and finally had found its most balanced and successful formula in the golden age between the WWII and the 90s.

OVERSUPPLY

Three colossal, converging phenomena, are now conjuring up to shake and topple the very foundations of the western society. Alpert describes the three fundamental hard facts we now have to deal with: oversupply of labour, oversupply of capital and oversupply of products.

Oversupply of labour is hardly in need of description, but to put the changes that are occurring into context, 15 years ago just a third of the Chinese lived in urban areas. Today, 51% do. The constant increase of the Chinese workforce will not plateau until 2020.

The Chinese labour force are saving an average of 53% of what they earn and this capital has been chasing investments and yield around the globe

India has an even bigger reservoir of untapped labour, with 69% of its population still living in rural areas. Half of all Indians are under the age of 25 and it is estimated that 275 millions new workers will enter the Indian labour force by 2030.

CAPITAL RESERVES

It is estimated that within 20 years, the emerging countries will have injected 20 billion new workers on the global stage. At the same time, the low wage, current account surplus nations (China, India, Brazil) and the energy exporting ones, like Russia and Saudi Arabia, have amassed enormous reserves of capital for themselves.

China’s reserves and savings went from $144m to $3.8trn. Russia’s reserves grew by eighteen times and Saudi Arabia reserves went from $21bn to $600bn and Brazil’s total reserves went from $33bn to $352bn. In total, the foreign reserves of emerging nations rose from $700bn to $7trn in less than 15 years.

The Chinese labour force are still saving an average of 53% of what they earn and this capital has been chasing investments and yield everywhere around the globe, ending up in large quantities in the pockets of consumption hungry economies, like the US were the current account deficit stands at less than $600bn.

The size of financial assets currently circulating stands at circa 10 times the global value of the world’s combined economies, and gives no sign of abating.

PRODUCTIVITY

More or less, in a perfectly overlapped pattern and timeframe, we have experienced the biggest increase in productivity (median average output per employee) ever recorded in the history of humankind.

This appears to have delivered an acceleration of +250% in the past 20 years. At he same time, median average wage has increased only by 8% accordingly to some sources, decreased by 7% accordingly to some others. In the US, as well as the EU, this has consistently diluted the purchasing power of the middle class.

Because the very foundation of our economies is based on the attribution of value of exchange to resources, products and services that are intrinsically scarce, the emergence of the age of oversupply with the speedy commoditisation of many goods and services, would pose huge questions to the model of our mercantile society.

GLOBAL INFLUENCES

The best-known futurologist and global influencer J Rifkin, foresees that we will soon hit the ‘Zero Marginal Cost Society’, where, thanks to technology and automatisation, the marginal cost to manufacture one more item/service will hit zero.

The profit will be equally reduced to minimal and labour will be made redundant in extensive quantities. It already is, with an estimated ratio of new technologies related jobs vs traditional economies-related jobs of 1:10.

Do we need to start rethinking how value is attributed in our society? Can we dare to re-imagine a model that served us well for hundreds of years? What is the value of goods, if not the price? What is the value of individuals, if not the paid-for labour?

A SHARING ECONOMY

Valentina Doorly

Part of the answer could be already taking shape before our very eyes. The sharing economy, for example, was born yesterday and it’s not making its way into our lives tiptoeing silently. It is an exploding phenomenon made possible precisely by the oversupply of goods and services, the automatisation of work, and the ubiquitous connectivity.

The sharing economy, for example, was born yesterday and it’s not making its way into our lives tiptoeing silently

The sharing economy puts to use overabundant resources that would have been otherwise sitting idle. It attributes a value to where there wasn’t any. It’s the home exchange holiday model, where houses are swapped without money transactions, or the extra room in your house put to use with Airbnb’s global machine turning the accommodation into a ‘liquid’ concept.

It’s the Dublin bike scheme, hop an go, and the Car2Go network across European cities where you flick open a car conveniently parked in the vicinity with your smartphone and you are good to go. It’s the snow plough machines purchased collectively by municipalities and shared through an efficient rotation system.

The sharing economy is here to stay and in its many forms – with or without monetary profits – it will redesign our ways of living and working and could possibly elevate our economic mechanics to a more advanced societal model. ‘Cooperative’ will be a word we are likely to hear a lot of in the near future. And it sounds like a good one.

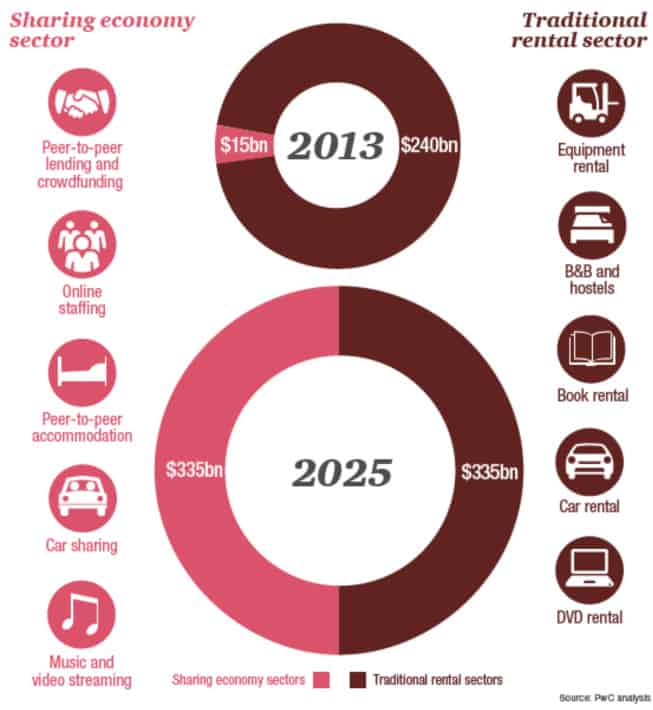

Sharing economy sector and traditional rental sector projected revenue growth