A crisis often brings about a change for the better and John Walsh outlines the economic and political reforms that Ireland will have to take to survive and thrive in the future.

The country is at a crossroads. The economic sovereignty of the State is under threat, following the worst property crash on record. The budget deficit is the highest in the euro zone and losses registered by the banks have been guaranteed by the State.

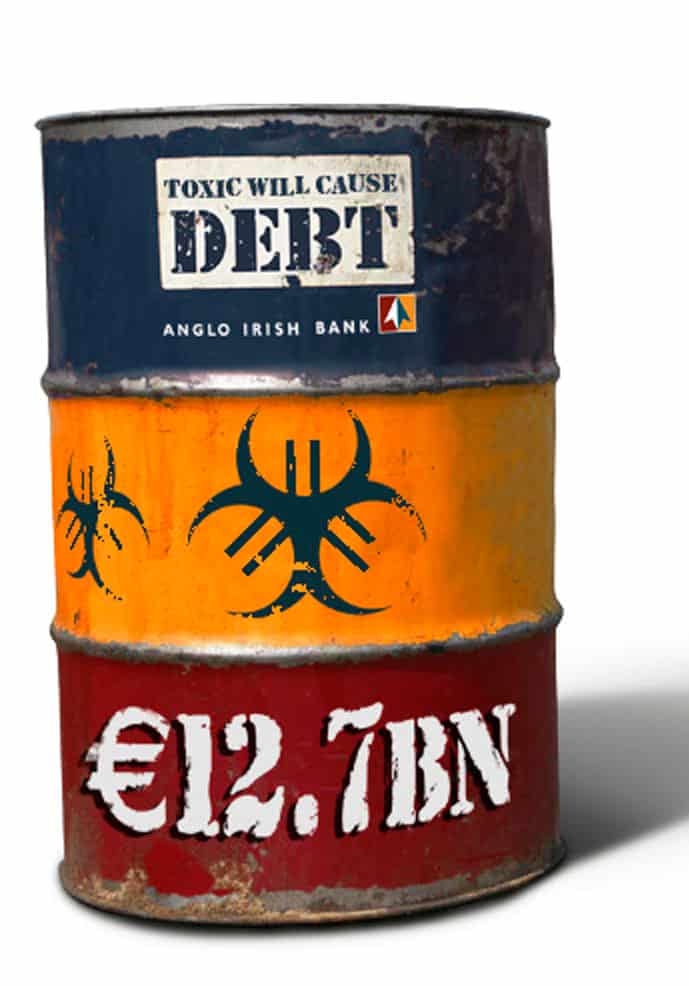

At the time of going to print, the full cost of the Anglo Irish Bank bailout had not been made available. Until such time as this figure has been made public, combined with full transparency on the final tab for the banks, then the bond markets will remain jittery. There are still a few hairshirt Budgets in store before the budget deficit is brought under control and within the 3% of GDP limit laid down by the European Commission.

If Ireland is to emerge from this economic maelstrom, then it will have to trade its way out. This article is by no means an exhaustive list of policy reforms that have to be implemented to get the economy up and running. But a radical reform package is needed.

The obvious place to start is reform of the public sector. The burden of adjustment cannot fall too heavily on the private sector as that will choke off the lifeblood of the economy. The forthcoming Budget has to strike the right balance between spending cuts and tax increases, again with one eye on economic growth. There has to be a clear political mandate for the tough decisions that lie ahead. The fate of future generations depends on the policy choices being taken now.

Industrial policy

That there is an unemployment problem in the country is not in doubt. Four years ago, this country had one of the highest employment rates in the EU. The jobless figure has now ballooned to almost 14% of the workforce.

There was a fortunate confluence of circumstances that caused the economy to boom in the early 1990s. Some of these were domestic factors and some were exogenous. The Irish Government opened up the economy. Trade barriers were dismantled, the corporate tax rate was made the lowest in the EU and the regulatory environment became much more business friendly. This co-incided with a one-off decision by US multinationals to locate abroad. Ireland soaked up a hugely disproportionate amount of this foreign direct investment. The complexion of the economy changed significantly over the next decade. The initial boom triggered a demographic dividend on the back of inward migration and one of the youngest populations in Europe.

The construction sector took off on the ramp-up in demand for housing. The Government introduced tax breaks for property developers in 2002 which co-incided with an unprecedented level of available cheap credit.

The economy became heavily skewed towards construction. The former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern still insists that the economy was heading for a soft landing from the dizzy growth rates of the middle part of the noughties. Only for the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the country would have muddled through.

But the over-reliance on the construction sector was always going to lead to huge problems, irrespective of the international backdrop. In 2006, there were 425,000 employed in construction and related activities. That was never going to be sustainable. Moreover, construction does not create a long-term development model.

There has been much criticism heaped on the Government for its alleged lack of jobs strategy. This magazine recently spoke to a senior businessman in this country who said that for the first time in the history of the State there is no coherent industrial development policy.

Philip Lane, professor of international macroeconomics at Trinity College Dublin, says that it is not possible to implement grand industrial strategies similar to the Telesis report in 1980 and the Culliton Report in 1992.

“It is one thing when you are making the transition from an agricultural based society to an advanced economy. There are things that you can do. It is not so easy to identify clear niches that you can pile into when you become an advanced economy like Ireland is now. There are limits to what the Government can do.”

The Taoiseach Brian Cowen as well as respective Government ministers have cited the smart economy as the way forward. That means penetrating sectors such as life sciences, nanotechnology, green technology, information and communication technology and financial services among others. These are the types of sectors that offer employment to highly skilled graduates. The country has a good foothold in pharma and medical devices. Companies in the business-services sector such as Google, Facebook and Ebay have also located here.

Alan W Gray, managing partner at the economic consultancy firm Indecon, says that the multinational sector has held up very well during the downturn. But there is only the potential to create another 30-40,000 jobs in this sector.

“This is the paradox of globalisation,” says Lane. “The internationally traded areas for a rich country rely on high-technology and high-skilled areas so more employment has to be found in the domestic economy. It will be the consumption facing services that will have to take up the slack.”

And this is where it becomes a chicken and egg scenario. For the domestic economy to pick up, there has to be a considerable upturn in internationally traded services. But that will not happen until there is a sustained improvement in the global economy.

Moreover, there are limited policy levers at the Government’s disposal to support internationally traded services.

Where the Government can make a difference is to tackle the cost base in State delivered services such as energy, waste disposal, water charges and other similar activities. There has been an improvement in the economy’s cost base, but employer groups like Ibec and the Small Firms Association (SFA) claim that much more needs to be done.

The quality of the country’s infrastructure, particularly in areas such as broadband, will be vital.

Possibly most important of all is the education system. For any country to thrive in the era of the smart economy, then it is hugely dependent on having a world-class university system with world-class research facilities with effective links to industry.

On a more macro level, there has to be a recognition that the balance of power in the global economy is shifting to emerging markets and, in particular, Asia. Government trade missions and IDA policy will have to become increasingly focused on this market in the future.

“There is a middle view of what the future holds for Ireland,” says Lane. “The decline in labour costs and rents etc means that there will be new opportunities especially for small firms where costs are paramount. But this is compromised by what is happening with the banks and the problem with access to credit. I don’t think the recovery will be wonderful but the economy will recover. But tax is going to have to go up a lot.”

Finance

Ireland is one of the most open economies in the world. A recent research note by the investment bank Morgan Stanley noted that if any country can get out of the current financial difficulty, then it is Ireland. This country is not like other periphery euro zone members because it was an open trading economy, the paper noted.

But access to credit will be a crucial determinant of the complexion and durability of the recovery. To this end, the prospects are uncertain. Irish banks have been through an unprecedented bout of turmoil since the collapse of the property market. Anglo Irish Bank has been nationalised and it is now in the process of being wound down.

The Financial Regulator Matthew Elderfield has laid down a series of capital ratios that the banks have to satisfy by the end of this year. Bank of Ireland has reached its target. AIB is divesting assets and has planned a rights issue in an effort to reach its target.

Whether it will be successful raising the capital through private means or whether the Government will have to take a majority stake in the bank remains to be seen. But one thing is for sure, the banks will spend the foreseeable future shrinking their balance sheets.

And this presents a catch 22 situation: as long as the banks are not lending, then that will weigh on an economic recovery. But the longer the economic downturn, then the increased cycle of bad debts which creates a disincentive for banks to lend.

The Government has proposed a credit review committee to look into the level of lending by banks to businesses. There is also a proposal for a loan-guarantee system Analysts are divided over how effective or appropriate this approach is likely to be.

“There is a complete lack of corporate lending at present. Companies used to deal with relationship managers, now they are dealing with the credit and legal departments. Banks are just not lending and that isn’t going to change when they get recapitalised for a few reasons,” says a former banker who moved to a corporate finance outfit.

He argues that in 2007, banks could easily go out onto the markets and raise finance on five-to-seven year terms. That is now down to two-to-three years, which means that banks will not be able to lend to corporates on a medium-to-long term basis.

Moreover, corporates that borrowed in 2007 will have to refinance in 2012. The former banker says these companies are going to have to start planning now for these debt roll-overs, which is going to take up a considerable amount of management’s time. The banks are likely to apply stringent terms when the finance comes up for renewal.

The solution could be in the capital markets. In the US, companies raise 80% of their funding needs from the capital markets and 20% from banks. In Europe there is an inverse relationship with 80% coming from banks and 20% from capital markets. This is set to change.

“Corporates will have to issue publicly listed bonds,” says the former banker. Traditionally, this market has been sclerotic in Europe, but 2009 was a record year for issuances. German mid-caps, which have spurned the equity markets, turned to corporate bonds as a means of raising finance.

Only Irish companies with earnings before interest and tax (Ebit) of €50m will have access to this market. But the theory is that when banks are recapitalised and corporates have refinanced their bank debt, that will trickle down to the SME sector.

Taxation

The tax system will be crucial. In the early 1990s, the corporate tax rate was lowered to 10%, which became hugely attractive for foreign direct investment. The corporate tax rate has since been raised to 12.5%, but it is still one of the lowest in the EU. This rankles with other member states. The French and Germans have argued that Ireland’s low corporate tax rate has fostered unfair competition and that it should be scrapped in exchange for a harmonised rate across the EU.

The European Commission has announced that it will publish proposals for a common consolidated corporate tax base (CCCTB) in 2011. The Government has resisted this move in the past on the grounds that it paves the way for a harmonised corporate tax rate.

“The 12.5% rate is totally within our control. There is a plan by the EC to publish proposals for the CCCTB in 2011 but it must be remembered that taxation is a sovereign issue and is covered by unanimity not qualified majority voting. Also, it is not as if this is Ireland versus the rest of the EU. Britain, Scandanavian and East European countries are also opposed to the CCCTB,” says Mark Redmond, chief executive of the Irish Taxation Institute.

But there is a more pressing concern. This magazine had a conversation with the influential Financial Times columnist Wolfgang Munchau in Brussels a few months ago. He argued that if Ireland had to tap the European Financial Stability Facility for emergency funds, then the corporate tax rate would almost certainly have to be offered up as a quid pro quo.

In view of the recent widening spreads between Irish and German government bonds, the markets are factoring in a much higher risk of a debt default by this country. If that were to happen, then the loss of economic sovereignty would make the scenario outlined by Munchau much more likely to happen.

Redmond says that the corporate tax rate is just as important now as it was in the early 1990s. “It is a really important element of brand Ireland. It is very important that in the next Budget the Government reaffirms its commitment to the 12.5% rate. It is as strategically important now as it has been in the past.

“Each member state has a different approach to tax rates it provides businesses. We are a small open economy in the EU. We rely hugely on foreign direct investment and for that reason, it is important that we have a transparent but low corporate tax rate. Other countries go for deductions and relief, many of which are not transparent.”

But Ireland is no longer the manufacturing hub it was in the early 1990s. Now the focus is on moving up the value chain into research and development. The head of one US multinational based in Ireland says that while the low corporate tax rate is still very important, the tax system has to be cognisant of the changing complexion of the economy.

Redmond says that some important measures have been introduced in this area. “The key one being the tax relief for research and development. It has been improved over the past five years. It is a very attractive one now.

However, one key improvement that could be made is that companies get relief on a volume basis rather than relief on an incremental basis on the increased spend over 2003 levels as is the system now. Also it should be better promoted among indigenous companies.”

Another crucial area involves personal tax rates, argues Redmond. The total level of taxation is 52% on an employed person and 55% for a self employed person in this country. If Ireland is to move up the value chain into the smart economy, then that means attracting mobile talent. But the personal taxation levels means that it is more punitive to work here than in competitor locations.

“The most effective way of broadening the tax base is to increase the number of people in employment. And for that to happen, you need to make it more attractive for people to work,” says Redmond.

The political system

Is the political system fit for purpose? There has been huge criticism of the Irish political system in the wake of the financial crisis. Eoin O’Malley, lecturer in the school of government and law in DCU, says reforms have to be introduced. “In 2002/03 economists were warning that there were problems coming down the line, but the political system was not able to act or react.” One of the biggest problems with the Dáil is the lack of expertise among its members. The gene pool from which TDs are drawn is very limited. There is a massive over-representation of school teachers and solicitors.

Then there is the amount of time that TDs spend on constituency work which leaves them very little time to work on policy at a national level. Consequently, power is concentrated at Cabinet level.

David Farrell, professor of politics at UCD, says that contrary to the view that there is a disconnect between the electorate and the political system, there is actually too much of a connect because of the single transferable vote system. This means that TDs have to spend a disproportionate amount of their time doing constituency work.

Noel Dempsey and Garrett FitzGerald have been among those advocating a change to the voting system. But O’Farrell says that this would not be enough in itself, there would have to be additional reforms. The reason why TDs spend so much time doing constituency work is that there is a complete lack of autonomy at local government level, which has the effect of constituents putting extra demands on TDs for access to local services.

Moreover, there has to be a big ramp-up in improvement in the way public services are delivered, says O’Farrell. He argues that the system is not user friendly which, again, puts pressure on TDs to act as intermediaries.

It also has to be made more attractive for people of all backgrounds to enter political life. The reason why there is a preponderance of school teachers, solicitors and publicans among elected representatives is that their professions afford them time to attend the committee meetings necessary when climbing the political ladder.

To reach Cabinet level, it usually requires a lengthy apprenticeship in the Dáil. People from business backgrounds don’t have the time to commit to political life at an early or mid-career stage.

O’Farrell says that to attract new blood, life in Leinster House has to be made more amenable to a greater cross section of society. That means looking at working practices and the amount of time spent in the Dáil chamber.

O’Malley argues that the link between the Cabinet and the Dáil has to be broken and that it should be possible to recruit ministers from outside the political realm. That would ensure that expertise is co-opted into the Government.