Numerous absorbing and dynamic interviews and features have graced the pages of Business & Finance during its history. Through the Decades looks back at a selection of articles, showing how the Irish economy has evolved.

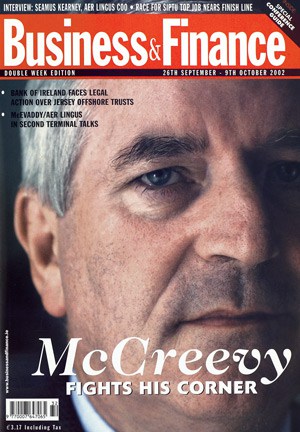

Charlie McCreevy, 2002

With the opposition calling for his head, and the electorate seething at what they see as broken election promises, Charlie McCreevy has had an uncomfortable few weeks, writes Ciarán Hancock.

Charlie McCreevy wouldn’t admit it of course, but the time has come to circle the wagons. With the opposition baying for his blood and accusing him of lying to the electorate about the state of the national finances before the recent election, he now finds himself on the butt end of fierce criticism from those in education and health, who are angry at the spending cutbacks and fee increases that are being forced on their areas.

There is also a growing chorus of economists and financial experts who say that his optimism about the health of the Irish economy is misplaced, while trade unions are pressuring him to deliver on benchmarking and warning that any new national pay deal will come at a price.

He was even booed by the normally reserved audience on last week’s The Late Late Show, which is hardly at the cutting edge of Irish current affairs. It’s been a difficult few weeks.

It’s mid-September, the weather is fine, the working day is drawing to a close and Charlie McCreevy is in chipper form. The public finances might be a mess, the national development plan behind schedule, Stadium Ireland a distant dream and unemployment and inflation on the rise, yet our embattled minister for finance still does a passing impersonation of someone who has lost a quid and found a tenner.

On the day of the interview, the UEFA delegation are in town to inspect our facilities, such as they are, for the hosting of Euro 2008.

Just an hour or so earlier their coach tried to gain entry to the courtyard of Government Buildings, beside the minister’s office, but found its way was barred by the low height of the gates that guard the complex. In many ways, it illustrates the problem for the bid team, given that soccer is currently barred from Croke Park.

GOVERNMENT PRIORITIES

McCreevy is said to have pulled the rug from under the Taoiseach on his pet project, when siding with Tánaiste Mary Harney in deciding that no public funds could be committed to the project in the medium term in advance of the fateful cabinet meeting just over a fortnight ago.

This is a charge vehemently denied by the minister, although it should be borne in mind that in the reports, which were carried in virtually every national newspaper, he was not subsequently challenged in print by his department.

“That’s a load of rubbish,” he says emphatically to the suggestion that he killed the Bertie Bowl. He shifts to the edge of his seat for emphasis.

“The fact is that the government came to a decision about its priorities. When this whole concept was being debated in its early stages both the Taoiseach and myself were very much in the forefront saying we were for a national stadium. I was then and I am now. But there comes a point when other priorities have to take precedence and the Taoiseach and the government recognised that.

“There are many things that we would like to do over the next year or two that we are not going to be in a position to do. On the scale of things that have to be done and on the scale of competing demands on public expenditure, the government will not be in a position to provide funding for a national stadium in the medium term and that is just recognising reality.”

REACTION AND DETRACTORS

Just when this reality finally dawned on the minister is not clear, although McCreevy insists that it was a recent realisation.

“Things move at a pretty rapid rate and the mistake that Irish governments have made in the past is reacting too slowly to events … and saying it will be alright on the night. It possibly could be alright on the night but there’s no point in waiting a few years before deciding that we should have made decisions back in 2002. There’s no rocket science about this, it’s simple.”

Of course his detractors would argue that McCreevy simply shut the stable door after the horse had already bolted given that the costs to date associated with the Abbotstown development are estimated to be in excess of €400m.

Things move at a pretty rapid rate and the mistake that Irish governments have made in the past is reacting too slowly to events …

But the Stadium Ireland controversy seems like a mere storm in a tea cup compared to the controversy that has brewed since the weekend following the revelation in The Sunday Tribune last weekend that the minister is planning €900m in spending cuts on existing services in 2003, along with a big hike in excise duties and only modest increases in personal tax bands. Tax increases could even be on the way and the confidential memo even raises the possibility of the retirement age being changed.

Given that public spending next year is expected to increase by around 9% and that the Department of Finance predicts that economic growth over the next three years will average out at 5% annually, cutbacks were inevitable.

SPENDING ‘ADJUSTMENTS’

But on Monday, news bulletins on both RTÉ radio and television reminded the public of a pre-election statement made by McCreevy in May which said that no ‘significant overruns’ were foreseen or cutbacks of any kind planned post the election. Since the election, spending by various government departments has been trimmed by €300m in a bid to check spending growth at 14.4% for 2002.

McCreevy prefers to characterise them as spending adjustments rather than cutbacks, and uses the analogy of a train decelerating from a break neck speed to one that might normally be found on Irish tracks.

“This year alone the Irish current and capital expenditure will increase by 14.4% [that’s the target but the final figure could yet be higher], which is a multiple of what any country in Europe is going to do. The previous year it was around 22% to 23% (taxes grew by a mere 3.2%),” he says.

“Some people say that increasing it by 14.4% is excessive and yet they’re saying that some adjustments in other areas to make sure we remain at this [level] shouldn’t be done either. So it can’t be both ways.”

OPPOSITION

“I find it somewhat amusing,” he says, in answer to this charge. “During the election campaign I recall one commentator saying that we were having accountancy classes at the Fianna Fáil election launches and I would have been at more of them than any other cabinet minister.”

He sits forward in his chair, warming to the task. “We adopted a particular strategy of talking about the economy and were criticised about that. I was asked on more than one occasion what it would mean in terms going forward and I said it would mean having sound budgetary policies, sticking with the terms of the [EU’s] Stability and Growth Pact and doing whatever was necessary. Most journalists sat there and were sleeping through it, except for George Lee on the days that he was there. That’s what we said we’d do and that’s what we’re going to do.”

So there you go, it’s our fault for not listening during the election campaign. With that he eases back in the chair and a slight grin appears.

SOLUTIONS

Of course, many would argue that there are two readymade solutions to the minister’s current funding crux, namely the scrapping of the extraordinarily generous SSIAs and a readjustment of the terms of the National Pension Reserve Fund.

Post the scrapping of the Bertie Bowl, the SSIAs came under the microscope, particularly as it offers a return from the government of 25% to savers over a five-year period. The uptake of the scheme, which closed at the end of April, exceeded the expectations of the Department of Finance with just over 1.1 million people over the age of 18 currently paying into it each month. This represents roughly two-thirds of the workforce. It is estimated that the scheme will cost the exchequer €1.25bn more than had originally been anticipated, with an extra cost for this alone of €170m.

It was launched at a time when inflation was high, consumer spending was out of control and nobody seemed bothered to save, mostly because of the low interest rates then on offer from the various financial institutions.

But the timing could hardly have been worse. At a time when the economy is decelerating, people are squirreling away up to €250 a month in SSIAs.

Joe Walsh and Charlie McCreevy

SAVING INCENTIVES

McCreevy, however, is unrepentant. “If that is a secondary effect then so be it, but the main purpose is to incentivise people to start saving again because that would have a beneficial effect on people’s lives into the future,” he says.

“That was the reason for it then and it remains the reason for it now.”

“So you’re not looking at scrapping the scheme?” I ask. “No!” “And you’ve no plans to change it?” “No!” “And you’ve no regrets over the timing of it?”

“You don’t have the luxury as minister for finance of every second weekend changing your budget … you try to make the best guess you can at the start of the year.

“Was it too generous?”

“The main thing was to think up a scheme that was attractive to people to do it. I think it will have a significant benefit to people for many, many years to come.” That’s for sure. Most people will receive their bounty in 2007, which if the coalition runs its course will be an election year.

Has he looked at the legal position (it has been suggested that individuals or banks might sue the government if the SSIAs are tampered with) if he were to cancel or change the scheme?

“As I’ve no intention of cancelling it, I’ve no intention of doing that [seeking legal opinion] either.”

He is similarly committed to the terms of the National Pensions Reserve Fund, which was set up in 2000 and requires 1% of GNP to be set aside each year by the government to meet future pension liabilities. Over €7bn currently sits in the fund.

Some economists have argued that this strict measure should be scrapped and replaced with one that might see 1.5% of GNP paid into the fund if economic growth exceeds say 4%, but only 0.5% if growth falls below this level.

Therefore, over the period to 2025, when funds will begin to be drawn down from the NRPF, the trend contribution should amount to around 1% annually.

CORPORATION TAX

McCreevy, however, flatly rejects this suggestion. “I heard all of that rubbish and academic argument when setting up the fund. It’s all academic rubbish because if you stop paying you’ll never start paying it again. Politicians will always find an excuse to pay something else. The political process being what it is that if it’s ever stopped it will never start again, not with all the best will in the world.”

“So under your watch it won’t change?”

“No,” he answers, “and funnily enough most of the Irish people in the last election in any surveys that I saw showed that they were supportive of it, in spite of the negatives from some politicians and a whole lot of academics.”

Post scrapping the Bertie Bowl, the SSIAs came under the microscope, particularly as it offers a return from the government of 25% to saver

Some opposition groups had argued in the election build-up that a revised rate of say 15% could be introduced without alienating foreign multinationals.

GLOBAL COMPETITION

But McCreevy is adamant that this will not happen. “No, there won’t be any change, you can be assured of that. Competitors abroad like to give the impression that the only reason driving foreign direct investment in Ireland is the corporation tax rate and I dispute that entirely, but it has been a key contributor.

“Tax rates are not the only part of the picture but it is very important to have certitude about it and the certitude is that under this administration we want to keep the corporation tax at 12.5%.”

The conversation eventually moves on to gaelic football, one of McCreevy’s sporting passions, and Mick O’Dwyer’s decision to take up a coaching post with Kildare’s neighbours Laois having parted company with the Lilywhites. McCreevy reminisces about how O’Dwyer reinvigorated the sport in the county and shrugs at his decision to join Laois.

Many Lilywhite fans felt that O’Dwyer’s time was up. Having led the county to two Leinster titles and taken them to an All-Ireland decider, the team is in decline and in need of new direction. For many, an apt analogy to apply to our finance minister.

Charlie McCreevy and Ray MacSharry, then chairman of Telecom Éireann

SETTING THE SCENE – 2002

By 2002, Sallins-native Charlie McCreevy already had over six years of experience with the finance portfolio.

As minister for finance, McCreevy had overseen the simplification of the tax system and Ireland’s changeover to the euro.

Few could have predicted what was coming down the line, but many would lay the blame at McCreevy’s feet.

Elsewhere in 2002, Irish voters accept the Nice Treaty; Geraldine Kennedy becomes the first female editor of The Irish Times; and the world mourns John B Keane, Spike Milligan and Richard Harris (pictured).