Marc Coleman is Founder of Octavian Research and Public Affairs consultancy. He discusses Ireland’s state of preparedness for the recovery.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is one of the world’s most respected forecasting and policy advice institutions. 10 years ago, this month, it forecast that Ireland would rebound from the last crisis to become Europe’s fastest growing economy. I organised a conference with attendees including the then Finance Minister, CEO of TV3 and Communicorp and Economics and Business Editors from RTE, Independent News Media and other groups. The event received comprehensive coverage and slowly but surely the recovery agenda gained prominence. Now, during a crisis running at five the speed of the last crisis, the OECD has issued surprisingly positive forecasts which imply that recovery is around the corner, or already begun, in many of the world’s economies. The question is, will Ireland miss out?

Pictured L-R: Marc Coleman and Brian Lenihan, former Minister for Finance

Back in April, in our publication “An Economic Response to Covid-19” we set out a conceptual timeline for crisis, recovery and normalisation. This envisaged the crisis phase terminating this year with recovery predicted for 2021 and normalisation beginning in 2022. This time profile was predicated on two key recommendations in the report, the first of which – a July stimulus – has happened and the second of which – a long term economic plan and investment focused Budget – is soon to be upon us.

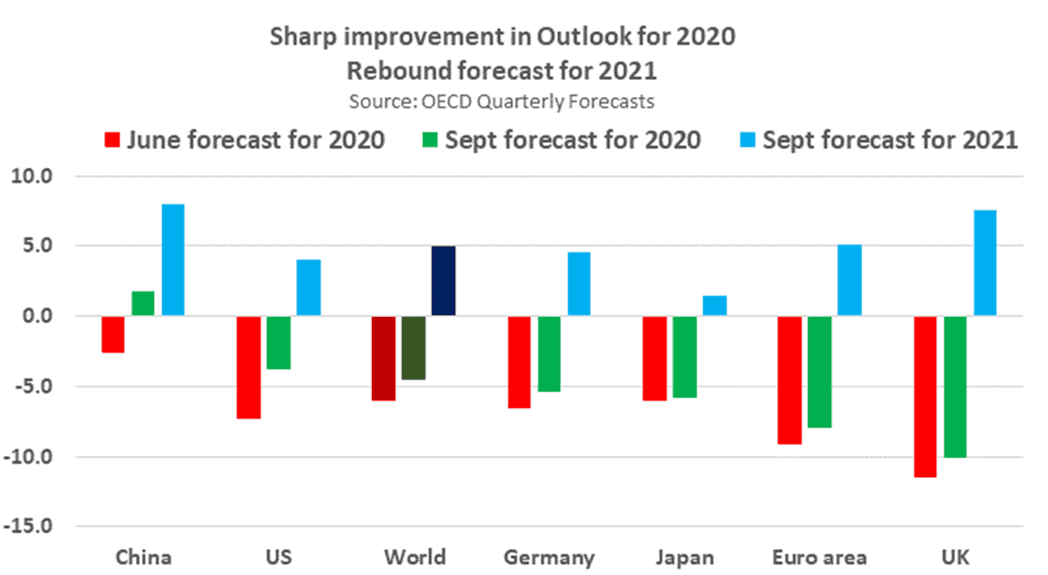

Greatly improved outlook for 2020 and 2021

The positive news is that, as the chart of forecasts below shows, a recovery in 2021 is – assuming forecasts are correct – clearly possible. The two challenges are, firstly, Brexit and, secondly, implementing a clear recovery policy in Budget 2021 and the National Economic Plan. From its June forecasted decline of 6.0 per cent for this year, the OECD has subsequently improved its outlook for world growth to a decline of 4.5 per cent.

Brexit: Double whammy or blessing in disguise?

Brexit is one side of a double whammy facing the Irish economy. Ireland’s diversification of trade in recent decades means that only 11 per cent of Irish exports are now destined for the UK. But that exposure to the UK understates a far higher exposure amongst food, fisheries and indigenous manufacturing exporters, sectors that are more employment intensive and more important to rural and regional economies. As far as the other side of that double whammy is concerned, and as outlined in “An Economic Response to Covid-19”, it is the indigenous non-export sectors that are already the most exposed to the Covid-19 recession.

As useful research from the ESRI and Department of Finance published this week points out, the areas of overlap are small: Few sectors are hit by both. But the sectors affected by Brexit and Covid-19 have one thing in common: They are much more likely to be indigenously owned, SMEs and based in rural and regional Ireland. For that reason, a clear strategy recommended in “An Economic Response to Covid-19” was to forge strategic partnerships between multinational companies and SMEs.

As well as establishing stronger supply chain relationships that will help safeguard SME viability, this strategy can also broaden the exchequer benefit from the multinational sector, a sector arguably overrepresented in Ireland’s corporation tax receipt performance but underrepresented in other tax heads. We have shown in our analyses of exchequer returns, the uneven profile of tax revenue performance during this crisis points to significant problems next year as corporation tax performance catches up with reality.

Another recommended strategy is to deepen diversification of trade. The better than expected economic performance this year is driven by US and China and by forcing Ireland to diversify to these markets, Brexit may force us to do what needs to be done in any event.

The US, German and Chinese economies – alternatives to the UK are forecast to recover at rates of 4.0, 4.6 and 8.0 per cent, respectively. The biggest challenge on this front is to ensure that our indigenous industries can leverage the depth and globalised nature of supply chains of multinational partners to develop the same kind of resilience to this recession. Other challenges include investing in skills provision, infrastructure – housing and public transport – and amenities to enable more economic activity to occur in lower cost and more “pandemic proof” parts of the country.

For social as well as economic (competitiveness) reasons: In many regions of Ireland the scars of the last recession have barely healed and a failure to revive local economies may recreate social and economic isolation unseen in Ireland since the 1980s or 1950s.

Marc Coleman is Founder of Octavian Research and Public Affairs consultancy and his latest book “An Economic Response to Covid-19” is available on www.octavian.ie. He is also a former ECB Economist, Irish Times Economics Editor and senior manager with Ibec.