To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Business & Finance, every Friday we will be taking a look through our archives and revisiting some of the key news stories, as featured in Business & Finance, that have shaped this country over the last 50 years. This week, we look at the swinging 1960s.

The 1960s

The rise and rise of Smurfit (1964)

In 1964 Business & Finance is born and a small paper and packaging company is floated on the Stock Exchange – Jefferson Smurfit Group. After devouring most of its Irish rivals, Smurfit turned its attentions to the US.

The first big move was the purchase of Alton Packaging between 1979 and 1981. This was followed up by the purchase of Publishers Paper in 1985. However, the deal which propelled Smurfit into the big time was the $1.2bn CCA acquisition in partnership with Morgan Stanley in 1986.

Just as cannily, the group recapitalised its American interests in 1989 and took out over £700m in cash.

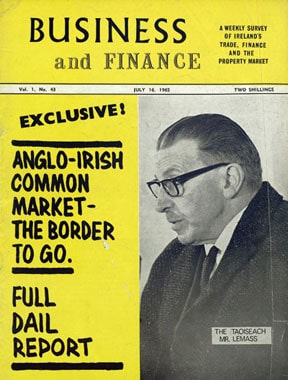

Can Irish industry survive free trade? (1965)

For industrialists, the agreement was a disappointing document. The much-abused 10% import levy remained with only manmade fibre producers seeing any gains. At the time, Ireland still had a manmade fibre industry and the likes of Sunbeam, Seafield-Gentex, Youghal Carpets and Irish Ropes were expected to benefit.

Lemass told reporters that he was confident Irish industry would continue to expand. He forecast that five new industries would spring up for every one that had to close because of the agreement.

It was believed that Fine Gael criticism would centre on the poor prospects for expanding bacon and ham exports. One industrialist summed up the reaction: “The agreement will play hell with the inefficient, especially after 1970, but that is as it should be.”

The great banking mergers (1966)

Bank of Ireland put the fear of God into its competitors when it took over the National Bank, creating a bank with combined assets of almost £290m and 230 branches. This was easily the largest bank in the country.

In August 1966, the Munster & Leinster, the Provincial and Royal joined forces to form AIB. It still lagged behind the enlarged Bank of Ireland with combined assets of £250m.

The mergers were welcomed by the Department of Finance and the Central Bank because they ensured that most of the Irish banking industry remained under domestic ownership. In 1965, First National City Bank (now Citibank) and the Bank of Nova Scotia had become the first North American banks to arrive on the Irish market.

In July 1966, United Distillers of Ireland – later Irish Distillers Group (IDG) – was formed from the merger of Cork Distilleries, John Jameson & Son and John Power & Son. Total profits for the merged group were only £400,000 at the time.

The merger brought together three of the most famous Irish whiskey brands – Jameson, Powers and Paddy. Bushmills, the other major Irish whiskey brand, was acquired in the mid-1970s.

Irish Distillers failed to achieve critical mass in export markets, although the merger gave it a virtual monopoly of the domestic market. In 1988, after an epic takeover battle between GrandMet and Pernod Ricard, the French firm emerged victorious in the battle for IDG.

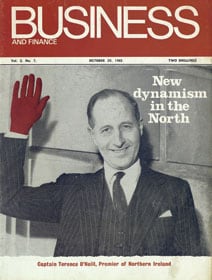

The North explodes (1969)

As the Civil Rights Movement of 1968-69 gave way to the IRA campaign from 1971 onwards, public opinion in the Republic was forced to look closely at its previously purely rhetorical commitment to Irish unity. The simultaneous rise of the loyalist paramilitary groups such as the UVF and the UDA made us aware, whether we liked it or not, that a majority of the population of Northern Ireland was implacably opposed to any form of Irish unity.

As the long nightmare continued and the death toll climbed to the 3,500 mark, the desire for unity was largely superseded by a wish to keep the North and its troubles at a distance. Atrocities like the 1974 Dublin and Monaghan bombings illustrated bloodily to those in the South that violence didn’t necessarily stop at the border.

The strike wave (1969)

In the early 1960s, Ireland had a strike record comparable to such economic paragons as the Netherlands and Belgium. We rapidly unlearned these habits as the decade progressed and by 1964 the number of days lost through strikes had more than sextupled to 545,000.

The turning point in Irish industrial relations was the 1969 ESB maintenance workers’ strike. One striker was actually imprisoned (he was quickly released and sent home by taxi). This ushered in an era of centralised bargaining.

Next Friday we will be delving into the 1970s.

*To read this article in its entirety, pick up a copy of the 50th Anniversary edition of Business & Finance, available now.