Numerous absorbing and dynamic interviews and features have graced the pages of Business & Finance during its history. From the Archives looks back at a selection of articles and shows how the Irish economy has evolved through the decades.

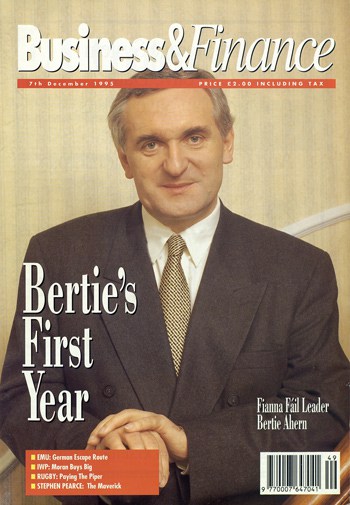

Bertie Ahern, 1995

In an exclusive interview with Dan White in late 1995, Bertie Ahern outlines his and his party’s likely policies on public spending, taxation, unemployment, exchange rate policy, dealing with the increasing crime wave and the economy in general.

While it may surprise many of those, this publication included, who criticised Ahern’s lax fiscal policies when he was finance minister between 1991 and 1994, tight control of public spending is likely to constitute a central part of any Fianna Fáil manifesto at the next general election, now most likely to take place in the summer of 1997.

Ahern does not see the policies which he has begun to espouse in opposition as representing a 180-degree turnaround from what he did in government but as more of a logical progression.

“I take responsibility for 85% of the 1995 Budget. I saw that we had a bit more flexibility in 1996 and 1997. That was the way I was operating. Like any good minister for finance I was targeting to have that bit at the end that would impress the people, not knowing that I would not even have the length of a campaign to get put out of office.”

The first real indication of Ahern’s tougher line on public expenditure came in a speech he delivered to Dublin Chamber of Commerce last September. In that speech he went out to dispel the old image of Bertie the spendthrift declaring: “The route to tax reductions lies in further reductions in borrowing and much tighter restraint on public expenditure.”

TAX CUTS

“We have been reflecting on where we are and where we are going. We believe that we have to restrain public spending after several years of rapid growth.”

The fiscal drift experienced between 1991 and 1994 was all the more disappointing when one considers that it followed immediately after the draconian public spending control exercises by Ray MacSharry. That, Ahern believes, was part of the problem. While MacSharry’s iron grip on public spending played well with economists, it went down less well with the voting public, particularly when it involved cuts to such public services as health.

“We did not pay any of the pay bills (the now notorious special increases) between 1987 and 1990. We had to pay them all back between 1991 and 1994. I was glad that I was there long enough to clear them all up. What I achieved is that there will not be specials of the same nature ever again. We effectively changed the system. Now any increase will have to be based on productivity or the restructuring of grades.”

When discussing what should be done on the public spending front, Ahern prefers to look forward. His hope is that both new government borrowing and the current budget deficit will be eliminated by 1999. “As finance minister I had achieved the elimination of the current budget deficit, which frankly, should not be difficult from here on. What is important is to eliminate the Exchequer Borrowing Requirement (EBR) altogether by 1999.”

GOVERNMENT BORROWING

Ahern’s determination that the EBR should be eliminated is well founded. With Irish growth rates as high as they are it is hard to make a case for any government borrowing in the current economic climate, as the European Monetary Institute (the European proto-Central Bank) pointed out recently.

“It is great that the latter part of 1993 was a good year and that 1994 and 1995 have been good years. 1996 might be a good year. But if we keep going this way, running a high EBR with high growth, what’s going to happen when we hit recession again? The reality is that it could lead to very serious problems in sticking to the Maastricht criteria.”

For a party which has traditionally done more than its fair share of taxing and spending, Ahern is promising that the 1997 model Fianna Fáil will be far more fiscally restrained. “Our 1997 policy will be borrowing and deficit cuts first, tax cuts afterwards.”

But if we keep going this way, running a high EBR with high growth, what’s going to happen when we hit recession again?

Traditionally, Irish finance ministers have looked upon ‘tax cuts’ as little more than an exercise in budget day sleight of hand. Reductions in one area were usually largely recouped under some new heading.

Ahern now believes that we must take a much broader view of taxation. “Taxation is a dimension of our competitiveness. In some areas such as the 100% corporation profits tax and the excise duty on petrol we are now very competitive with Britain. But income tax, employers’ PRSI and the general rate of Corporation profits tax are a very different story.

“The position is that every year the minister for finance gives back about £100m in tax cuts. That is only one twenty-fifth of the £2.5bn required to service the (national) debt. We would be in a far stronger position to give real reductions in taxation if the public finances were stronger.”

ACTION ON PRSI

One area of taxation where Ahern believes that urgent remedial action is required is PRSI. He argues that the lower rate of PRSI should apply to all incomes up £15,000 in 1993 terms.

While Ireland’s fiscal numbers currently look good, the fact is that they are seriously flattered by EU transfers, currently running at about £1.5bn a year. The problem with such transfers is that they are likely to begin to tail off from the end of the century.

For a start, in 1999 the current situation where the whole of the territory of the Republic of Ireland qualifies for objective one status for the structural funds comes to an end. Instead we will have to re-ague the case for as much of the country as possible. While we are likely to continue to do well from the Cohesion Funds and the CAP, the manna from Brussels is hardly likely to flow as freely as we have become accustomed to. “From 1999 the flow of resources from Brussels will diminish. At the same time we could be heading back into recession. In addition interest rates could move back up. All of these three items create pressure on the budget. What do you do then?

“You either have to cut expenditure or increase taxation. The problems is not just to cut taxation now in good times but to guard against having to put it up in bad times.”

After less than a year as finance minister, Ahern received a though-going baptism of fire when the country was pitched into the currency crisis following sterling’s ejection from the ERM in September 1992. Despite that traumatic experience, Ahern remains convinced that we should adhere to the Maastricht criteria and be ready to sign up for EMU in 1999. However, he is not blind to the risks which a lax fiscal policy poses for Irish hopes of EMU membership.

“We satisfy the Maastricht criteria, we are not looking for opt-out clauses but if we hit a period when EU resources are diminishing, economic buoyancy in Europe is decreasing and interest rates here are increasing we could find ourselves caught in an awful bind.”

EMU MEMBERSHIP

But surely a far greater threat to Irish hopes of EMU membership comes from the possibility of Britain opting to stay out? Surely our adherence to the Maastricht criteria will count for nothing if our largest trading partner chooses to have nothing to do with the new European currency?

Ahern recognises the dilemma confronting Irish exchange rate policy but feels that a tight fiscal policy gives us the greatest control over our own destiny.

“We have to make sure we are in a position to make the decision (about whether or not to join the EMU) on day one and that it is within our call. Otherwise it would be a disaster for us. That is why controlling the debt, adhering to the Maastricht criteria and the EMI guidelines are absolutely vital for us. Because at least then we can say: “Are we going in fully or do they want us, or will we go for some kind of special relationship (with EMU) that the British have?”

While Ireland’s fiscal numbers currently look good, the fact is that they are seriously flattered by EU transfers

When it comes to the proportion of national output which the State spends, Ahern believes that the current level of approximately 43% of GNP is about right. However, he believes that even if one accepts such a level of growth in public expenditure targeted by the Rainbow Coalition is too generous. “There is no pressure in any of the key areas of public expenditure at the moment, whether it be health, education or (social) welfare.

There is no pressure whatsoever. With the buoyancy in the economy and 49,000 more people working, the PRSI and social welfare funds in good condition, it is not the time to be increasing spending.

“Within every department there are opportunities to tighten up. In 1987 in bad times we were able to cut spending by 5% in almost every department. Now that we have good times I have no doubt that there are opportunities to tighten up over the next few years.”

PUBLIC SPENDING

The problem with across the board cuts in public spending is that, as soon as the reins are relaxed, spending picks up again. Fianna Fáil and Ahern himself found this out the hard way between 1990 and 1994. Surely if one is serious about lasting reductions in public expenditure one must identify complete programmes which have outlived their usefulness?

“We have gone through every area in every department. We are not going to highlight those in advance and open up a hornet’s nest. We have gone through all of the expenditure subheads of all areas.”

According to Ahern the exercise has divided public services into one of five categories:

- Where the State should link up with the private sector to provide a service

- Where the State is providing a service which is no longer serving any useful function

- Where the service could be modified to provide it in a far more cost-effective way

- Essential services where essentially there is nothing much the State can do except to continue to foot the bill

- Services not receiving sufficient resources, especially the fight against crime.

BUDGET DEFICIT

While naturally reluctant to give hostages to fortune by naming precise areas, Ahern promises that the exercise will be complete by Easter 1996 and the party will give a broad indication of the amount of money that can be saved.

The Fianna Fáil aim will be to hold public spending constant in real terms, eliminate the current budget deficit and to dispense with the Exchequer Borrowing Requirements by 1999.

If Fianna Fáil returns to government and carries out Ahern’s stated intention of holding public spending constant in real terms, then it will take only very modest economic growth to free up serious money for tax cuts. Who is going to be at the receiving end of this hoped-for largesse?

“We want in the first instance to make employment an attraction to our workforce and our unemployed. Secondly we want to take more low-income workers out of the tax net altogether. One of the ways we believe we can do this successfully is to introduce a new introductory tax rate of 230%. Thirdly we want to increase substantially the thresholds at which people enter the higher tax bands.

“We must make sure that nobody, particularly those on lower and middle incomes, pays more than a maximum of 50% on additional or overtime earnings in combined tax and PRSI.”

PROPERTY AND CORPORATION TAX

Other tax changes likely under a Fianna Fáil government would be special measures to assist pensioners.

Ahern points out that many people are now retiring at 55 or even 50 rather than the traditional 65. In his view, these people are now are being ‘crucified’ by the current taxation system. The Residential Property Tax so beloved of the Dublin middle classes also faces the axe.

On the corporation profits tax front an Ahern-led government would extend the 10% rate to more activities in the internationally traded services sector.

Ahern feels that a tight fiscal policy gives us the greatest control over our own destiny

While in theory one would be better off with a single low-ish composite rate of corporation profits tax, in practice one is stuck with the present two-tier system.

“I used to think that (favour a composite corporation profits tax) but having talked to a lot of the 10% companies I’m fearful of what might happen (if it were removed or increased). But I do think that the top rate (currently 38%) is too high and that there is an argument for reducing it over time. The higher rate is too punitive.

“If you are looking for people to reinvest, it is too high. Particularly now where there is so much technology that people have to reinvest.”

FINANCIAL SERVICES

While Ahern has reluctantly concluded that we have no choice but to stick with the special 10% rate of manufacturing corporation profits tax, he is far more agnostic on the 10% for financial services companies located in the IFSC. Our exemption from the EU runs out in 2005 and Ahern believes that these companies will end up paying a higher rate of tax after that.

And what about capital gains tax? At 40% our rate is extremely high by international standards and compares with 15% tax rate levied on special savings accounts.

“Our capital gains tax structure is a recipe for everyone using legal tax planning to get around it. It should be far simpler, there is far too much legislation in this area. What we are trying to do at the moment is to come up with proposals to rationalise it and make it simpler. It’s a nightmare at the moment.”

UNEMPLOYMENT

Taxation policy is not just about maximising Exchequer revenue. It, in conjunction with the social welfare system, also has major implications for the operation of the labour market. This was demonstrated by the most recent Labour Force Survey, which showed a gap of almost 90,000 between the numbers signing on and those actually unemployed.

“If unemployment is a problem and we want to continue to get people off the dole and give them the dignity of work and not be giving them money for nothing, we have to look at tax incentives for employers if that is what it takes, as well as lowering PRSI.”

Our capital gains tax structure is a recipe for everyone using legal tax planning to get around it

He also believes that the tourist season, which now runs to 30 weeks a year, provides opportunities for creating jobs for the long-term unemployed. While Fianna Fáil has not unnaturally exploited transport, energy and communications minister Michael Lowry’s difficulties over the semi-state sector, in practice its policy on these companies has always veered towards the pragmatic rather than the ideological. After all, as Ahern points out, the two major Irish privatisations, Irish Life and Greencore, occurred under Fianna Fáil-led governments.

“It is impossible to generalise. Each case should be dealt with on its own merits. The policy should not be ideologically driven because that would be a mistake in a small country.”

Certain State-owned companies, he points out, may have capital needs or partnership requirements, which cannot be met by continuing 100%, State ownership. Ahern recalls his willingness to sell off majority stakes in the State-owned banks to create the so-called ‘third force’ when he was minister for finance.

SOCIAL ISSUES

While tax and unemployment are important issues so far as most people are concerned, they are not the most important.

Private opinion polling by Fianna Fáil has shown that the issue of greatest concern to most people is our burgeoning crime wave. It is not surprising then that, in his recent Ard Fheis speech, Ahern devoted so much attention to crime.

In Ahern’s view crime is now virtually synonymous with drugs. With an estimated 80% plus of crime now drug-related that is a difficult contention to argue with.

He outlines a number of measures he would like to see taken. For a start he reckons that there should be a major education programme to alert children to the dangers of drugs.

On the enforcement side, he would like to see the guards getting increased surveillance powers. This should go hand in hand with the power to search and seize and should be co-ordinated at national level with the Revenue Commissioners.

“It is ridiculous that people have to be going down to court to get warrants for traffickers who are moving huge amounts of deadly stuff around. You wouldn’t have to do that if it was machine guns they were moving around.”

He also calls for increased community information about crime and drugs along with adequate treatment for addicts. The other measures he is calling for are more prison space and a reform of the bail laws. The crime issue is a drum that Fianna Fáil will beat very loudly at the next election.

SETTING THE SCENE – 1995

1995 was an engrossing one in Irish life and Ahern had just completed his first year as Fianna Fáil leader in late 1995 when this interview took place.

Earlier in the year, then taoiseach John Bruton, and Gerry Adams held their first formal discussions and the British prime minister John Major and Bruton launched the framework document regarding Northern Ireland. 80,000 people cheered Bill Clinton at College Green in Dublin for his work during the peace process in December of the same year.

A referendum was held in November, where Irish citizens voted narrowly to allow divorce. 1995 also saw Seamus Heaney win the Nobel Prize for Literature; the first airing of Father Ted; Jack Charlton’s retirement as manager of the Irish soccer team; as well as Steve Collins’ defeat of Chris Eubank to defend his WBO super middleweight title in Millstreet, Co. Cork.