Numerous absorbing and dynamic interviews and features have graced the pages of Business & Finance during its history. From the Archives looks back at a selection of articles and shows how the Irish economy has evolved through the decades.

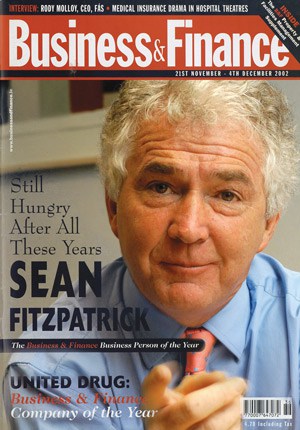

Seán FitzPatrick, 2002

Over the past two decades he has built one of Europe’s fastest-growing banks, almost from scratch. He has modelled its management style closely on his own principles of hard work and strong reward for risk. Seán FitzPatrick talks to Vincent Wall about the triumphs and tribulations of his career.

It’s one of those bleak Saturday evenings in March and Seán FitzPatrick is struggling through Dublin’s outer suburban traffic on his way home to Greystones. He has spent the afternoon in Mullingar, watching the Wicklow under-21 Gaelic football team take on Westmeath in the early stages of the Leinster Championships.

FitzPatrick is a sports fanatic, particularly when it comes to Greystones Rugby Club and Glasgow Celtic FC where he holds a season ticket. He’s not however particularly into Gaelic football. But in this instance, the son of one of Anglo Irish Bank’s longest-standing clients, property developer Sean Mulryan, is playing on the Wicklow team. The bank has sponsored their jerseys and FitzPatrick has given up one of his weekend leisure days to support father and son.

The episode is synonymous with the way Seán FitzPatrick has run the bank since he took over as chief executive in 1986. His personal philosophy of getting to know the detailed requirements of his customers and of sweating all the hours available during the working day − and weekend if necessary − to provide them with a swift and tailored service, has become second nature to the near 1,000 bank employees who now work in Ireland, the UK, Switzerland, Germany, Austria and the United States.

It’s a philosophy, solidly anchored on a lean, innovative and tightly focused banking model that has propelled Anglo Irish Bank from a minor and frequently disregarded fringe player to one of the largest and most profitable companies on the Irish Stock Exchange.

By any standards the rate of growth has been phenomenal, particularly over the last five years. When FitzPatrick took charge 16 years ago (he had worked for various affiliates for the previous 12 years), Anglo Irish Bank was generating pre-tax profits of £200,000, had a net worth of £3.5m and a total of 60 employees. Ten years later, by 1996, it had grown profits to £23m, risk assets to £1.5bn, while its market capitalisation had advanced to over £180m.

Later this month when it reports preliminary results for the year to September, it is expected to dazzle the market with pre-tax profits of over €250m and total risk assets in excess of €19bn. At time of going to press, the group’s market capitalisation, at a share price of €6.69, had soared close to €21.8bn, with most market commentators confidently predicting it to move higher when the results are confirmed.

If these top-line numbers are impressive − so much so that at one stage last year Anglo was the fastest-growing bank in Europe − then so too are the longer-term trend statistics.

Seán FitzPatrick leans back and smiles, his trademark brightly coloured tie lighting up the early morning gloom of his office. An accountant by training, he loves nothing better than to reel off the exponential numbers that stand as milestones of his and his organisation’s success.

“I would say our performance could be attributed to good people, good luck and good planning, in that order. There hasn’t ever been a culture of long-term planning in the bank, but we sowed the seeds in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s when we worked terribly hard to get where we are today. Our thinking then was pretty short-term because, at the time, it was mainly about survival and about trying to find a niche where we could distinguish ourselves in the front row of banks,” he notes.

The strategy that emerged was that of a specialised or bespoke − to quote Anglo’s own description of itself − business bank. It would concentrate its energies on small and medium-sized businesses, particularly those investing in property or other securable fixed assets. Its rapid and flexible decision-making process would make loans available to such enterprises more quickly and with less fuss than the larger general banks, which it would encourage its clients to retain for their other banking services.

Costs would be kept to a minimum by centralising all lending, credit control and treasury operations and by eschewing the opening of branches outside the major cities. These lower costs would allow it to offer significantly higher deposit rates to attract retail funding, a major source of its capital requirements.

GOING THE EXTRA YARD

FitzPatrick is the first to acknowledge that the strategy reaped more bountiful dividends by coming to maturity just as the Irish economy went into overdrive from the early to mid-1990s. But he stresses that the real driver of the bank’s initial and continued success, is the people who work in it.

“The management hasn’t changed that much here since the late 1980s. It’s a very experienced team at the top, but not necessarily that old in years. By and large we pay people better than the other banks, but that’s really a by-product of their success, it’s not what motivates them in the first place.” He switches to a sporting analogy, one of his favourite methods of explaining what he means. “Why does Roy Keane go that extra yard for the ball when David Beckham doesn’t, they’re both paid the same. It’s internal. I think we’ve a lot of Roy Keanes with a very clear view of what they want to achieve. But they know that if they do, they’ll be rewarded well.”

Hmm, obviously, the positive aspects of the Cork man’s character are what FitzPatrick has in mind. While Anglo has aggressively headhunted from other banks for the self-starting employees it requires, it is also quick to get rid of those who don’t fit the mould, for whatever reason.

“There’s no room for middle men here, or those who like to find refuge in the activity of the group. If you’re good and confident at what you do, servicing your customer and growing the bottom line, then this bank will provide an ideal platform for you on which to perform. Our guys have to treat the money they lend as if it was their own. We make them proprietorial and that makes them think differently about what the bank does, right down to whether the lights are turned off in the evening or the front-of-office staff are sufficiently courteous to customers.

“We’re pretty adamant about that in here. We fired a guy at last year’s annual management get-together, because collectively we didn’t respect his performance and attitude to people. We didn’t think it was right for a senior manager in a bank. Yes, I agree, some people would find it very hard to adapt to a culture like that, but I think it must be one of the most demoralising issues for staff in a large organisation; to witness mediocre service on offer from their colleagues and nobody doing anything about it.”

His own appetite for hard work and his competitive streak go back a long way, to his childhood in Bray and to the playing fields of Presentation College where he excelled at underage rugby. “There’s a hunger in me that comes from the way I was brought up. My late mother in particular ingrained in us that we had to keep striving and that enough was never enough. And I’m still as hungry and passionate about this organisation as I’ve ever been despite the number of years I’ve been in the job. For me, and I think for everyone else who works here, there’s an intense satisfaction from building up a hugely successful institution within our own relatively short career spans. That’s not available in the larger banks and that helps us get out of bed early on cold, winter mornings.”

If you were to ask me what could really go wrong for us, apart from a very sharp general economic downturn, I would say a rapid escalation in interest rates

Because, Seán FitzPatrick, as reward for his achievements, now enjoys a very nice lifestyle indeed, and last year was the highest paid banker in the country and perhaps second only to Michael Smurfit in the entire Irish corporate sector.

According to the 2001 Anglo Irish Bank annual report, his overall remuneration amounted to €2.1m. This comprised an annual salary of €460,000; an annual bonus of €381,000; a deferred bonus of €190,000; a pension contribution of €135,000 and benefits of €35,000. In addition, he was awarded a once-off additional bonus of €952,000 to reward him for the bank’s ‘exceptional’ performance and for signing a new agreement to remain as chief executive for a minimum period, thought to be to the end of 2003.

The report shows he also owns over 3.5 million ordinary shares, equivalent to over 1% of the bank’s entire equity and currently valued at €23.7m. And he has options over a further 632,000 shares exercisable up to September 2005.

“Yeah, I’m enjoying life now and it’s well known that I take a fair bit of time off during the year. But I think it’s a fair return for the very long hours that I put in when I’m here and for the loneliness and pressure of continuing to over-achieve. I’ve had no overt negative criticism at all about how much I’m paid. Strangely perhaps, for Ireland, most people have said well done. My board has never intimated that it was undeserved in any way and our shareholders, broadly speaking, are delighted with our performance. One of my senior executives actually went out of his way to say to me that the more I earned, the more he earned, and the happier we all were.”

And as he points out, the bank has created over 15 other millionaires at senior management levels over the past decade through its generous options policy.

Nor is it that Anglo’s services come cheap for those that avail of them. At an NCB banking conference earlier this year, FitzPatrick in his own colourful but hugely forceful presentation style, suggested that if his employees were to march up and down outside its HQ on St Stephen’s Green waving placards advising customers that they charged more than the other banks, they’d still win the custom. According to a recent interview with Peter Butler, head of banking in Ireland and the US, the current margins are between 2.5% and 3%.

“I’ve huge respect for the way most other banks conduct their business here. And by and large they are less dismissive of us now, but they still can’t compete. They can’t offer the same high deposit rates, because of the sheer volume of their retail base. Our business model has got to a stage now where no rabbits have to be pulled out of a hat. It’s solid, sustainable and supported to a very large degree on repeat custom. I mean, 70% of our new lending last year came from our existing client base.”

MODELS AND BLUEPRINTS

So what exactly is the model? FitzPatrick and his colleagues certainly haven’t gone out of their way to hide the blueprint in their presentations to investors, the media and other stakeholders.

“We don’t lend to specific business sectors. We lend to businesses so that they can invest in fixed assets. We secure our loans against those assets and we service them from the income streams generated. So while it’s true that we have exposure to hotels, pubs and investment properties − as well as the business premises purchased by professionals such as doctors, accountants and dentists − we are not exposed fully to the economic vagaries of those sectors because our investment is in their bricks and mortar.

“Sure, we can’t in any way afford to be complacent as the economy slows down. But we know that in that scenario, people will actually deal more with an experienced niche bank like ourselves, because we can provide them with a more tailored service. If you were to ask me what could really go wrong for us, apart from a very sharp general economic downturn, I would say a rapid escalation in interest rates.”

He continues: “Because we have a lot of annuity income coming in secured on property, if interest rates shot up suddenly we’d be in trouble because the income streams couldn’t support the higher rates and it would take two to three years to adjust. But the medium to long-term interest rate outlook is benign and we have extra protection in that our lending activity is increasingly spread across the UK as well as Ireland.

“In fact the proportion of the bank’s lending carried out across channel is fast approaching 50%, where it is far more focused on commercial investment properties than it is in Ireland. “How big can we grow in the UK? There’s no limit. If you look at how we’ve grown in recent years, it’s largely been organic. There have been no transformational deals such as IAWS’ Cuisine de France or Irish Life’s acquisition of Irish Permanent.

“We’re using the exact same model in Britain. It’s a much bigger market but we haven’t been piling people in there trying to ramp it up. Britain is not a foreign country anymore, it has the same general culture, legal system and type of lending as we do here. It’s true that only 2% of our loans there are to Irish people, but a lot is channelled into similar ethnic groups such as the Jewish community, who operate on the same tight-knit, word-of-mouth principles.”

INFERIORITY COMPLEX

As a further guarantee to its shareholders, Anglo has also long operated a very prudent loan provisioning policy. Some analysts now see this policy as being over prudent and suggest that the gradual release of up to €136m from this effective capital base could enhance earnings significantly over the next few years.

“Well, clearly we haven’t been engaged in trying to smooth our earnings growth, that would be against good plc practice,” FitzPatrick notes softly, but with just the slightest flash of his sharp green eyes. “Our policy has evolved from the time we were much smaller and when we needed to win the confidence of both our depositors and our lenders. I suppose you could say that it’s evidence of a little bit of an inferiority complex still. As an institution we’ve come from a position of childhood, through adolescence and young adulthood. We haven’t fully matured yet, I would accept that, but I’d also hasten to add that we’ve seen no sign of deterioration in our asset quality out there.”

FIRST ACTIVE DEAL

There have been mistakes of course down through the years, and adjustments. In the early 1990s, Anglo made relatively disastrous forays into stockbroking in Ireland and asset leasing in the UK. The acquisition of one or two loan books did not bring the benefits anticipated, and its share price suffered for many years because of a perceived over use of rights issues to feed the capital base required for its rapid growth.

More recent expansion into private banking services in Ireland, Austria and Switzerland have helped push revenues from fee income to over 15%, but these activities, while undoubtedly successful, are unlikely to be pushed too aggressively now in the current depressed stockmarket environment.

It would have given Anglo access to First Active’s treasury operations, amongst other benefits, but effectively fell apart because the bank’s then chairman Tony O’Brien and other board members declined to allow First Active chairman John Callaghan assume the chair of the newly enlarged entity. FitzPatrick himself later ran foul of financial journalists for effectively denying the existence of a deal proposal, up to and until it began to fall apart.

“That was a really, really difficult time for the bank and was the first time we had genuine tensions at board level, which impacted on senior executives as well. I enjoyed dealing with John Callaghan and Cormac McCarthy of First Active, but our board felt because we were the stronger party, that we should get more of the top jobs. We were a bit too greedy in that respect.

“We had a full debriefing after it came unstuck and analysed how it was all handled with the board and the media. If I could rerun events, I’d do things very differently and I’d handle the board in a different way. But I learned a lesson and those board members learned a lesson. It just shows that between the ages of 51 and 54, you can still have some maturing to do.”

Despite some suggestions to the contrary, he stresses that the deal is unlikely ever to be resurrected because of the divergent, if successful, directions in which both companies have moved in the interim. As to the future generally, he acknowledges that Anglo Irish Bank stakeholders have one big question in mind.

We fired a guy at last year’s annual management get together, because collectively we didn’t respect his performance and attitude to people

“I think if people are of a mind to judge my performance at all, it will be evaluated by the timing of my departure, the way it is done and the manner in which my successor takes over. I am still passionate about this bank and still have some goals to achieve, but I’ve got to give it up at some stage, or I’ll kill it.

“I’m 54 now and I’ve always said that executives should retire before they’re 60. I’ll certainly retire before I’m 57 and it could come as early as 55, I don’t know. I do believe there are times when it’s like half-time in a match and you’re out there giving the team talk. When you look up and see people mouthing your lines about two seconds before you do, then it’s really time to go.”

GRADUAL UNWINDING

He affirms that when the time comes, it will be the responsibility of the board to assess all possible internal and external candidates, but he suggests that in his own view there is sufficient talent within, to fill the post. He acknowledges that in some quarters there have been whisperings that the bank won’t be the same without him. It annoys him at times but he stresses that institutional investors are perfectly comfortable with the depth and experience of its management team. And, true to the talents of a one-time rugby half-back, he neatly sidesteps the next potential trick question.

“I’m not saying I’d like to be the next chairman of the bank, but I would like the position at some future date. While I acknowledge the argument, that like Matt Busby my chairmanship might stifle the next CEO, I think it would be better for Anglo, if there was a gradual unwinding of responsibilities. I would also say in my defence that I have continued, over the years, to change my role here, from a hands-on control freak in the early days to being able to delegate nearly everything, as I do now. And I’ll be able to change again.”

But what if all these plans came to nothing and the bank was acquired over the next year or two, by a non-Irish institution looking for a strong business banking presence here? He maintains, as he long has, that he doesn’t see it happening. But if it does?

“There are no contracts here and no poison pills to cause pain to somebody who might try to take us out. We don’t need it to grow, but if the right price was offered and we wanted to compress shareholder value, then I’d recommend to the board to sell it on. Our price is about €6.70 today and some analysts say we are currently worth up to €8.50. So any realistic bid would have to about €11. In that event, price would talk. Clearly we’d have concerns about stakeholders such as depositors and employees, but the prime consideration would always be, shareholder value.”

Still passionate and hungry for greater success, but ultimately pragmatic: Sean FitzPatrick, Business & Finance, Business Person of the Year in 2002.

SETTING THE SCENE – 2002

During 2002, Irish voters accepted the Nice Treaty, Geraldine Kennedy became the first female editor of The Irish Times and the world mourned John B Keane, Spike Milligan and Richard Harris.

The country went into World Cup frenzy mode one again as Ireland performed well in Japan and South Korea – minus Roy Keane, who had left the camp after incidents in Saipan. Draws with Cameroon and Germany, followed by a 3-0 victory over Saudi Arabia, brought Ireland to a last-16 tie with Spain. Ireland were unlucky to be defeated by La Roja on penalties.