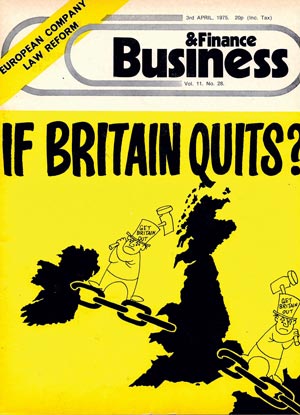

A new series on Ireland’s post-Brexit future kicks off with five things we know about the UK’s departure – and five things we don’t.

Since Theresa May’s triggering of Article 50 on March 29th, the Brexit dust has started to settle.

The initial shock of the referendum result lasted over six months: since June 2016 UK public debate has consisted of the broadest possible gamut of reactions, from triumph to despair – and it’s not always been particularly polite or constructive.

UK/EU tensions are long-standing

In Ireland, meanwhile, the widespread sense that the UK has committed an act of self-sabotage has been nuanced by considerations that Ireland could be in line to win new business – or be badly hit by possible economic ill-effects in store for its nearest neighbour.

Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty lays down a two-year timeframe for the EU and UK to agree a divorce deal and for the UK to establish a new relationship with Europe and the rest of its trading partners. From now on diplomacy, bureaucracy and minute attention to detail will be the order of the day.

Business & Finance will be there all throughout, covering every aspect of a momentous occasion; the latest instalment in a story that began as Ireland and the UK prepared to enter the EEC together in 1973 – and now Ireland will be left to go it alone.

From now on diplomacy, bureaucracy and minute attention to detail will be the order of the day

Five things we know about Brexit:

Brexit means Brexit

Theresa May’s post-referendum catchphrase took time to flesh out, but we now know that the UK is leaving the EU and indeed leaving the single market – both things that couldn’t be taken for granted in the aftermath of the vote. Separation will be total and a brand new trade deal will be required between the two parties. Economic independence is the aim, joining long-standing conservative/right-wing grievances over justice and immigration.

The timeframe

The 2007 Lisbon Treaty specified a mechanism for a country to leave the EU. Both sides will have two years to negotiate, starting when Theresa May’s ambassador handed Donald Tusk the most famous letter in modern European history in March.

Who’s in charge… for now

May looks secure in the short term, with Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn weakened amid party disunity. Angela Merkel’s leadership is comfortable until she has to focus on going to the polls in September. There seems little prospect of a comeback by anti-Brexit forces. UKIP is in disarray. SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon is perhaps the most secure of the main Brexit leaders.

Irish attitudes are stable

Anti-EU sentiment tends to grow at referendum time – but despite residual anger over ECB and European Council roles in the recession and bailout there is little or no appetite for an Irexit. Meanwhile, there is relatively little to divide Government and opposition voices on the Brexit issue.

Ireland’s ‘special case’ attitude gaining traction

Taoiseach Enda Kenny claims that most European leaders acknowledge that Ireland is a “special case” due to the border and Good Friday Agreement – though it’s too early for Angela Merkel to agree.

Five things we don’t:

Border blues

The return of customs posts and a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic is a disheartening prospect for border communities, cross-border businesses and exporters. Likewise, a row over the status of Gibraltar highlights problems with rebuilding borders and sovereignty in general.

Political instability

France goes to the polls in April, with Francois Hollande not running. Meanwhile, at home Enda Kenny is expected to hand over the reins this year to a successor who will have to placate independents and Fianna Fáil. Scottish independence or united-Ireland attitudes could gain traction, with Nicola Sturgeon announcing plans for a second referendum to leave the UK.

Irish domestic economy

Property prices, homelessness and the cost of living are key issues in spring 2017, with Minister for Finance Michael Noonan announcing a predicted 4.3% GDP growth for the year. How the Irish economy will look at the end of the Article 50 period depends on an unusually volatile set of factors.

Who’s jumping ship

Can Ireland attract businesses that are fleeing the UK? Particularly City of London financial services firms? There are big prizes being fought for, with the IDA in Ireland’s front line.

Deal or no deal

Can the UK and EU agree a deal? What will it look like? If not, the UK reverts to World Trade Organisaiton rules. Deal or no deal, either scenario will have enormous – and complicated – implications for Ireland’s relationship with a main trading partner.