Numerous absorbing and dynamic interviews and features have graced the pages of Business & Finance during its history. From the Archives looks back at a selection of articles and shows how the Irish economy has evolved through the decades.

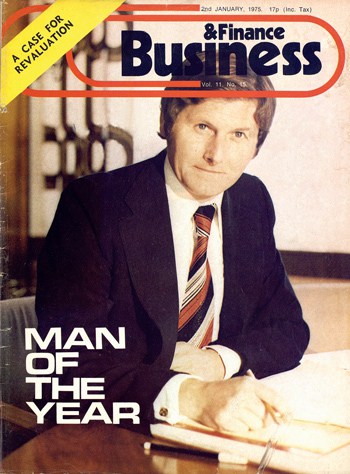

Michael Smurfit, 1975

In 1975 Michael Smurfit was announced as the Business & Finance ‘Man of the Year’. Here, Jim Dunne speaks to the Smurfit Group manager about how the Group has achieved its success and why he believes the government has been slow to react to changing times.

In accepting the ‘Man of the Year’ Award, the boss of the country’s most successful company in 1974, remarked: “I take the award as the head, but it is a group achievement.” For many people on whom an award is bestowed, this is a form of words which in all hypocrisy must be gone through. In their heart of hearts they may believe themselves to be the greatest, but they know that society’s conventions do not permit them to say so.

Michael Smurfit moved with ease among his people, who seemed to view him with as much affection as awe. Geographically speaking, there was no top table, conspicuously separated from the hoi polloi. There happens to be a table where Jefferson Smurfit Senior sat, and also Michael; but Jefferson Junior was not at it and neither were most of the divisional managing directors. The only patriarchal note was when Michael Smurfit addressed the gathering briefly about the company’s performance in 1974 and at some length about the difficult times ahead.

The managers gossiped − as managers will − about their bosses, but there was no hint of disloyalty. It would be stupid to declare definitely on such slight experience that Smurfit Group is a happy place to work, but it seems to be more exciting and more rewarding than most. What is certain is that Michael Smurfit is the source of most of the excitement. At one point in the evening I was explaining to my neighbour who I was and why I was there. “I am probably the only person in the room that does not work for the Smurfit Group,” I said. “That could change before the night is out,” replied my neighbour.

INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS

The Group now employs directly about 6,500 people, and a further 4,000 indirectly. I put it to Smurfit that it was remarkable how few strikes they had. “It is not due to our unique abilities in industrial relations,” he said. “Our factories are mainly small units. I can readily understand British Leyland’s problems. We had a small stoppage this year in Ireland, no more than four or five days, and it was unofficial.”

Smurfit does not object to worker participation as an idea, but he dislikes the word. “After all,” he says, “I consider myself to be a worker also. I prefer the word ‘co-determination’. The other expression contributes to the division between workers and management − them and us. In any case, we will wait to see how the system works out in the State bodies first, to check what the benefits are.”

OUTLOOK

Smurfit is very critical of companies who do not inform, or misinform the trade unions about the company’s position. “There is no wolf-wolf in this company,” he says. “Never threaten unless you are prepared to carry out the threat.”

Smurfit is no happier than most people with the prospects 1975 holds out. “Nobody who has subsidiaries in Britain can be anything but worried. The grip of the left-wing is very strong, and there is no evidence of the unions maintaining the social contract: look at the Yorkshire miners!”

He is convinced that statutory controls on wages and incomes will have to be introduced, though he is dubious that Harold Wilson is the man to provide the strong government which must back such a policy.

The grip of the left wing is very strong and there is no evidence of the unions maintaining the social contract …

Notwithstanding that, he remarks that the Smurfit operation in Britain is a very small one in a big economy, “so we can hope to get business from bigger companies”.

LEADERSHIP

Political leadership in this country also gets the sharp end of his tongue. “I am continually disillusioned by the lack of leadership the Irish business community has had over the years,” he says. He criticises in particular the decision to change our mining concessions.

“We reneged on our word,” he says, while agreeing that the concessions may have been overgenerous. “We changed the rules unfairly. You do not invite a team to play soccer, and then when they are on pitch inform them that the game is going to be played according to the rules of rugby.”

GOVERNMENT POLICY

Smurfit believes the government is far too slow over exploratory licenses. “We must as soon as possible set about reducing our dependence on Arab oil,” he says.

He expressed amazement that the government is being so slow in getting an energy conservation policy off the ground. There should, he believes, be very strict legislation on insulation in buildings, double-glazing and other sensible devices to make the best use of the energy that must be consumed.

This latter complaint is, he claims, widely shared in the business community that believes that “when George Colley went to finance he took industry and commerce with him”.

He agrees that there should be a Mergers Bill “if only for the protection of people and companies”, but one fault he finds with the present proposals is that the size criterion is far too small.

MERGERS AND TAKEOVERS

Smurfit is well-known of course for his belief that mergers seldom work, as well as outright takeovers. “With mergers everyone sits on the board,” he says disparagingly.

I reminded him of his reputation as a cold and rather ruthless man which dates more or less from the takeover period of Hely and Browne & Nolan. He did not deny the charge, simply remarking that those two companies, and also Temple Press, needed “a pretty substantial shaking”.

At that time, he conceded, a very tough, no-nonsense approach was necessary. It no longer is. “Our people and now highly geared,” he said, lapsing into a jargon which he generally succeeds in eschewing.

On his desk as we talked I noticed a wad of 100-franc notes. It prompted the question, “How is the Paris experiment going?” The answer to that was short and snappy. “We’re closing down Paris, certainly for the immediate future. We got our timing wrong.

“Our sort of business is going through a bad patch on the continent. Then our communications between Paris and Dublin were chaotic between a long postal strike and an unsatisfactory telephone system.”

“Are you disappointed?” I asked. He was, but was brisk about not wasting time on emotion. “It would have been inept not to take our losses and clear out. He is a silly man who goes out into a force 10 gale when all he is capable of managing is a force 5.”

He has, however, long-term faith in France − and Ireland too for that matter − as countries which, for all their industrial progress, are still capable of feeding themselves and others.

When we spoke, Smurfit was just back from a six-day visit to Japan where he had discussions with a giant paper packing company, the fourth largest in the world, on ‘mutual cooperation’.

“Would you like to tell me more about that?” I asked optimistically. He smiled and said he would not, at least for the time being.

I am continually disillusioned by the lack of leadership the Irish business community has had over the years

I asked Michael Smurfit finally if he was a patriot. “If you mean by that do I support Ireland, her culture, her institutions and do I pay my taxes, the answer is yes. I have made my home here. After 20-odd years with the Smurfit Group, I have financial independence; I could live elsewhere. One puts a certain value on the quality of life, though it must be said that the burden of taxation here is crippling. We live too in fear of expropriation.”

“Is that not dramatising things a bit?” I asked. He returned to the changing of the rules over the mining concessions. How, he implied, can we have trust if our political masters do not keep faith. It was a sombre note to conclude on, but neither Michael Smurfit nor anybody else in business is getting ready to light bonfires.

SETTING THE SCENE – 1975

In 1975, Smurfit Group was operating in Ireland amongst 450 foreign-owned industrial projects which accounted for two-thirds of Ireland’s total industrial output.

While the new multinational companies brought success, many older Irish businesses found it difficult to adjust to the new open trading conditions.

For the first time Ireland held the presidency of the Council of the EU, while Charles Haughey was being brought back onto the Fianna Fáil front bench.

Other news headlines in 1975 included the death of former revolutionary, taoiseach, and President of Ireland, Éamon de Valera, and the death of three members of The Miami Showband in a Ulster Volunteer Force ambush in Co. Down as the musicians returned home to Dublin from Banbridge.