Marc Coleman, economist and founder of Octavian Consulting, discusses what a Victory-shaped recovery looks like and the likelihood of it happening.

Let’s start with a quiz. It’s the morning before a loved one is due to have a life-saving operation. You are visiting them in hospital, maybe for the last time. The surgeon says there is a 50-50 chance of them surviving. The question is, when talking to them at their bedside, which 50 per cent do you focus on? Right. We don’t need further discussion on that. Instead, let’s focus on what the surgeon does. No operation is guaranteed to succeed but long and messy operations put a patient’s metabolism under strain and prolong the chances of failure or death. Well-planned and executed operations tend to take less time. No prizes for guessing which one has a greater chance of success.

But what is a V-shaped recovery? Can it really happen? A perfectly V-shaped recovery, one which quickly self-reverses itself in the same time as the recession took to materialise, is the economic equivalent of a unicorn. That is, it doesn’t exist. But an imperfect V-shaped recovery is possible.

One reason the last recovery took so long – and that its impact carried forward in our last general election – is that policy responses were agonised, protracted and imbalanced. By putting disproportionate strain on weaker sectors of the economy, public and private sectors, the low-paid service sector workers (whose pay has barely risen above crisis levels during the recent recovery) were hit by regressive taxation and/or pay cuts that damaged consumer spending the most. Couldn’t more have been done instead to reduce wasteful spending? The case of the Children’s hospital would suggest so. Social injustice aside (the political results of which now coming through in elections loud and clear) an adjustment strategy that most hurts those for whom consumer spending is a higher share of disposable income will be disastrous to an economy about to be hit by an appalling shock to consumption. The reverse approach now needs to be taken.

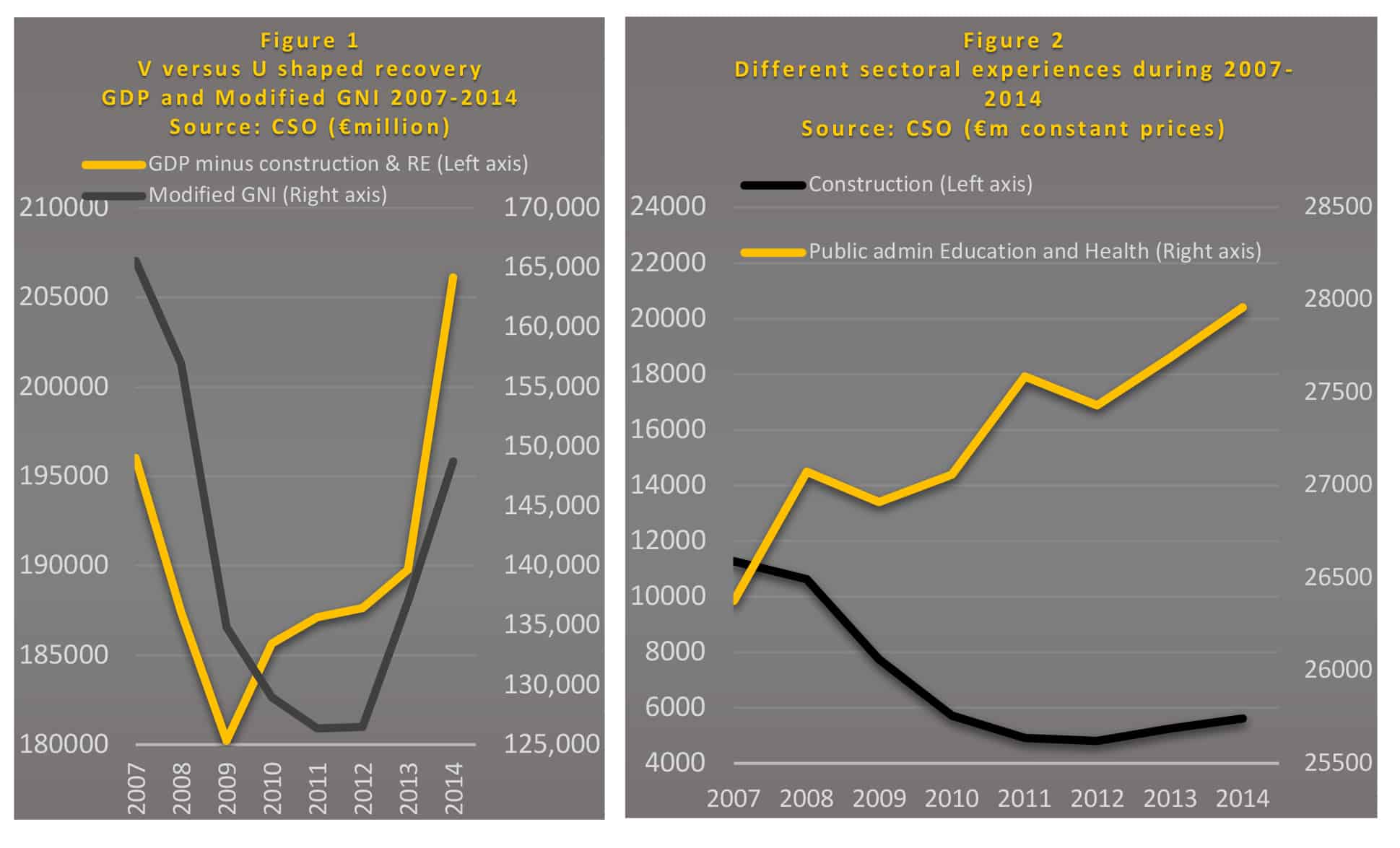

But what is a V-shaped recovery? Can it really happen? A perfectly V-shaped recovery, one which quickly self-reverses itself in the same time as the recession took to materialise, is the economic equivalent of a unicorn. That is, it doesn’t exist. But an imperfect V-shaped recovery is possible. To see how, compare the two lines, yellow and black, in Figure 1 below.

The first shows the GDP, minus construction and real estate. Taking a traditional measure of the economy, GDP, but excluding sectors most affected by recession, it shows how something close to a V-shaped recovery was achieved when the worst of the domestic recession was factored out. The bounce-back began as early as 2009 and continued unabated (albeit slightly slowed). However, as the black curve shows, a measure of more domestic activity (GNI* which captures more adequately the domestic economy adjusted for distorting multinational and intellectual property and domicile transferring activity) suffered prolonged recession for 4 years.

What Figure 2 reveals is that this was a partly avoidable tragedy. We didn’t and don’t control the global economy, a point elaborated below. We did, however, control the distribution of government spending and as Figure 2 shows, contrary to much narrative about harsh austerity in current government spending, current government spending on Public Administration and Health actually grew over the crisis (albeit with interruption) by some 6 per cent.

By contrast Construction activity, significantly due to massive cutbacks in more employment-friendly construction spending by the previous government, fell dramatically by 50 per cent. As wages were lower in the construction sector every €1 million spent by government on capital spending should (with proper cost control) create more employment.

A different spending strategy, one of prioritising capital over current spending as I advocated over 2008 to 2014, could have created a very different outcome for construction employment and also in relation to our housing crisis. I also advocated on several occasions and platforms a reform of the Fiscal Treaty to separate the current from the capital account to enable younger, fast-growing countries with greater housing investment needs to spend in that area without being penalised for what is a legitimately different fiscal situation compared to countries with older populations like Italy or Germany (where saving is more important).

A different spending strategy, one of prioritising capital over current spending as I advocated over 2008 to 2014, could have created a very different outcome for construction employment and also in relation to our housing crisis.

Finally, the point has been made that we cannot control the workings of the international economy. In the short term that is true. But as I made clear in my 2013 book (Ireland and Germany Partners in European Recovery) and again in my 2014 book (Unlocking Asia’s Trade potential for Ireland), we can control our response to it. Since those books were published, our exports to Germany and Asia have increased dramatically both in absolute terms and as a share of exports. Geographically, our trade is much more diversified than before. By now targeting a sectoral diversification, with the IDA and Enterprise Ireland collaborating to link our SME and Multinational sectors more closely, we can overcome much (but not all) of the coming crisis.

For Coleman’s weekly updates see Businessandfinance.com