Marc Coleman, economist and founder of Octavian Consulting, discusses Ireland’s response to Covid-19 and the difficulties that face policy makers.

The current Covid-19 crisis has revealed a heartwarming level of national solidarity and mutual support. But we might consider an exchange that took place on a farm long ago between a chicken and a pig. The chicken says to the pig on the morning of the farmer’s breakfast: “We’re both in this together.” The pig replied “Yes, but you’re merely involved whereas I’m committed.”

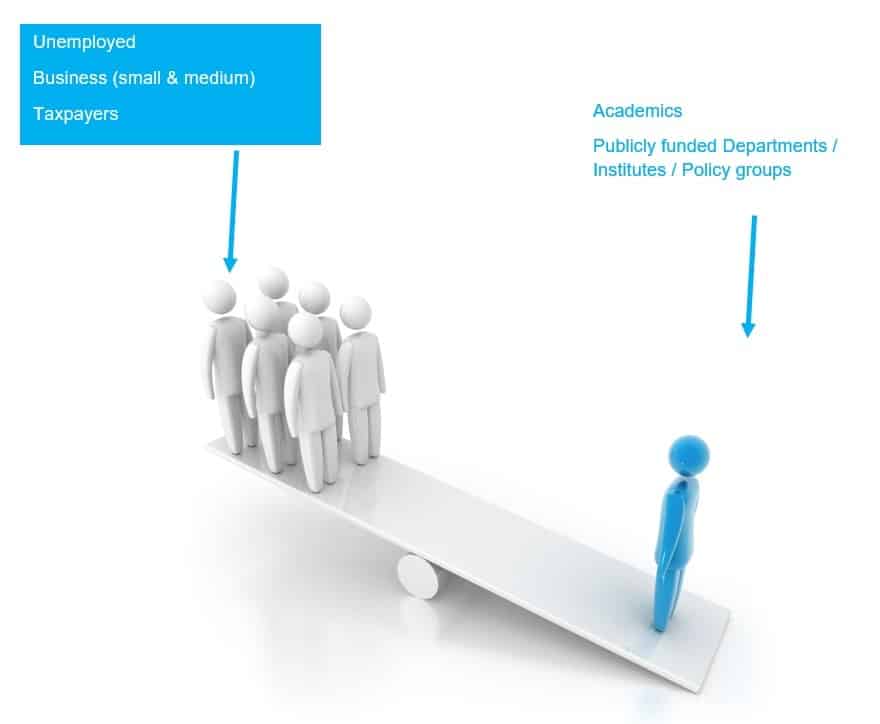

Those most affected by this crisis are the ones with the weakest voice in policy-making circles.

As ESRI, Central Bank and Central Statistics Office (CSO) data and analysis all confirm, when it comes to job losses and business failures, the private sector will bear the brunt of this crisis. To the extent that we borrow from future generations this will mitigate the immediate consequences of Covid-19 for us. But to the extent that our generation bears the cost, it will be overwhelmingly be borne by the private sector. Within the private sector, the largest corporations have the greatest resources to withstand the cashflow and regulatory challenges created by Covid-19. Medium and small sized companies – already hard-pressed by weak consumer demand (arising from policy choices that favoured increased current government spending over a restoration of after-tax pay during the recovery) and by a lack of funding – are more “committed” than any other sector in this crisis. Of the 694,000 workers currently claiming pandemic unemployment payments, the vast majority are from this sector.

These protocols raise more questions than they answer: How, for instance, can data from testing employees for Covid-19 be used under GDPR? How are small business supposed to handle the overtime costs of staggering work hours to ensure social distancing?

Which leads us to what I call the “policy response conundrum”: Those most affected by this crisis are the ones with the weakest voice in policy making circles. With virtually no resources and from a standing start the “SME Recovery” group has made a stand for the SME sector. Welcoming in a constructive fashion government measures taken to date – and they are welcome – it has nonetheless pointed out that the sheer magnitude of the crisis demands a response on a much higher level than originally envisaged by policy makers.

Policy makers themselves come overwhelmingly from sheltered sectors of the economy where redundancies, liquidity crises and the constant stress of the business world are unknown or understood only at a theoretical level. Which is why I always smile when I hear University academics commenting on business policy. A bit like a man commenting on childbirth.

Last Saturday the Local Employer Economic Forum (LEEF) issued protocols for employers re-opening their businesses. These protocols raise more questions than they answer: How, for instance, can data from testing employees for Covid-19 be used under GDPR? How are small business supposed to handle the overtime costs of staggering work hours to ensure social distancing? How are they supposed to fund the renovation of bathrooms to ensure staff answering a call of nature at the same time are socially distanced? If an employer gives a Covid-19 positive employee the right to work from home and other staff denied this right resent it, could that employer face discrimination or favourable treatment claims? The list goes on. Hopefully LEEF will give guidance on these and other questions facing and worrying employers right now.

But it would be much more helpful if policy making bodies like this – including the National Pandemic Emergency Health Team (NPEHT) – were far more representative of the private as well as public sector. The roll-out of testing and tracing – which has extended the lockdown and will delay its wind down – is a case in point where greater know-how could and should have been exploited more quickly.

We are, for now, in this together. But when the money runs out hard choices will have to be made about continuing to fund non-viable entities.

Even in the private sector, thinking needs to change. There are suggestions that funding should be prioritised for the University sector. Arguably, that money would be better spent on funding higher-level training to refocus workers from areas where jobs have been lost to new growth sectors of the economy. Universities are not famous for agility of response to rapidly changing labour market developments. Third level private sector colleges – the ones facing the greatest crisis from loss of international students – are. A better solution right now would be to use the full force of the National Training Fund to support agile and responsive jobs-relevant led training. After that, urgently required and productive medical research should be a key priority. Beyond that, significant reforms and efficiencies – and greater openness to new ideas, work and recruitment practices – are needed to justify any more money for the University sector.

We are, for now, in this together. But when the money runs out hard choices will have to be made about continuing to fund non-viable entities. As that happens, expect the debate about public sector reform – starting with the least efficient and least “front line” relevant sectors – to escalate dramatically.