Marc Coleman is founder of Octavian Research, an economic research publication and public affairs consultancy.

Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Which is benefitting which: Is the deficit being helped by good tax returns, or are tax returns inflated by the impact of borrowing?

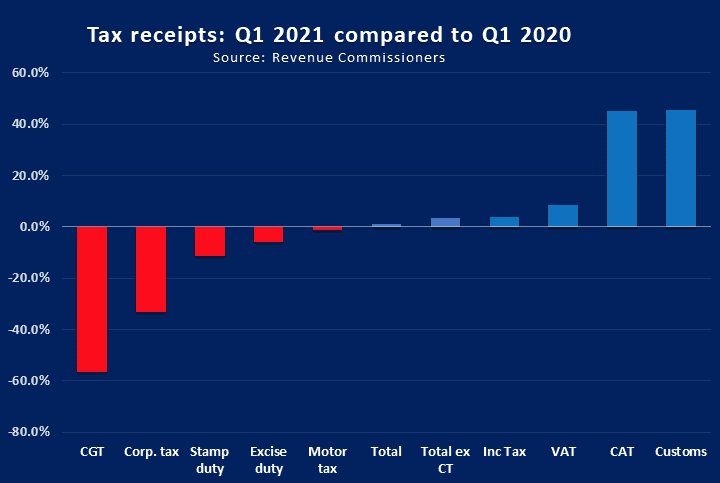

The latest exchequer returns for the first quarter of 2021 seem relatively positive. Overall the tax take is 1 per cent above that recorded in the same, largely “pre-Covid-19” period of 2020. Some tax revenue categories – Capital Acquisition tax and Customs – are up substantially.

Income tax and VAT are also modestly up. Others such as Capital Gains Tax, Corporation Tax and Stamp Duty receipts are down substantially.

Most analysts have concluded that the latest figures are supportive of the government’s efforts to reduce the deficit. It would be great to be able to agree. Sadly, close analysis shows a different picture.

To understand why, we need to understand that these are influenced by a mixture of cash as well as accrual approaches to timing. Secondly, we need to understand that different tax heads have different time lags between the economic activity that drives them on one hand and, and on the other their tax performance.

The latter is why we persistently argued that – despite strong increases in corporation taxes in the middle of last year – this was cold comfort: Those increases reflected not the state of the economy in the middle of 2020, but rather the strength of the economy in the twelve months leading to 31st March last year, a period for which many companies report profit and on which corporation tax liabilities are calculated. That period – devoid of Covid-19 for 95 per cent of its length – was a gangbuster year for the economy.

As these latest exchequer returns have shown, and as predicted, corporation tax returns are now beginning to reflect the impact on the exchequer of lockdown: Compared with Q1 2020, corporation taxes in Q1 2021 were down a whopping 33 per cent.

Capital Gains Taxes were down a staggering 56.5 per cent and stamp duties were down by a more modest but still serious 11.3 per cent.

As we move into Q2, the year-on-year comparisons will start to benefit from lower base year effects and this will moderate large declines somewhat. At the same time, towards the end of this year another factor will kick in: The government will aim to reduce borrowing. And here is where, unfortunately due to lack of resourcing in the media, economic analysis and commentary is failing to understand the real underlying picture.

Simply put, and in terms of the chicken and egg metaphor, in so far as any positive news is contained in relation to tax returns – and the positive growth of 4 per cent and 8.4 per cent in income taxes seem positive – it is the sheer size of exchequer borrowing that is mainly responsible with some additional impact of a fillip for VAT arising from the few weeks of spending spree during the Christmas and New year lockdown interlude. To put it in even simpler terms, in the twelve months to end March 2021 the government recorded a €14 billion exchequer deficit. In other words, government put an amount of money into the economy equivalent to approximately 7.5 per cent of Gross National Income (modified).

Given that Ireland has amongst the highest marginal income tax rates and highest indirect tax rates in Europe if not the world, it would be highly surprising if that did not result in a temporary fillip for those tax heads – income tax and VAT – that are most benefited by short-term measures such as employer supports and the PUP.

In summary tax, returns will begin from Q2 and Q3 on to iron out the time lag distortions of the lockdown on tax returns. But as they do, and from Q3 and Q4 onwards, they will also fully reflect the state of a post lockdown economy from which most of the deficit financed props have been fully withdrawn or are being fully withdrawn. At the very least, government needs to improve its own understanding of how the taxed economy influences its revenue. This is particularly so as, contrary to most electoral cycles, governments normally hold back from borrowing in the first half of a term before taking the foot off the brakes in the second half. This time, it will have to work the other way around.

Marc Coleman (marc@octavian.ie) is founder of Octavian Research, an economic research publication and public affairs consultancy that wrote the world’s first researched strategy response to the Covid crisis (download www.octavian.ie ) and currently produces the world’s first weekly Covid-19 specific economic and business client research note (now in its 32nd edition). He works with leading clients across industry, financial services and government agencies to produce policy influencing research and publications. He has authored five influential books on the current and previous recoveries and worked as an economist with the European Central Bank, Department of Finance, as Economics Editor of the Irish Times and Newstalk 106fm, a Sunday Independent columnist. He is a leading speaker, event host and policy analyst.

Marc Coleman (marc@octavian.ie) is founder of Octavian Research, an economic research publication and public affairs consultancy that wrote the world’s first researched strategy response to the Covid crisis (download www.octavian.ie ) and currently produces the world’s first weekly Covid-19 specific economic and business client research note (now in its 32nd edition). He works with leading clients across industry, financial services and government agencies to produce policy influencing research and publications. He has authored five influential books on the current and previous recoveries and worked as an economist with the European Central Bank, Department of Finance, as Economics Editor of the Irish Times and Newstalk 106fm, a Sunday Independent columnist. He is a leading speaker, event host and policy analyst.