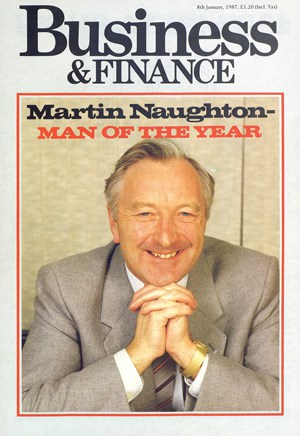

Numerous absorbing and dynamic interviews and features have graced the pages of Business & Finance during its history. From the Archives looks back at a selection of articles and shows how the Irish economy has evolved through the decades.

Martin Naughton, 1987

Glen Dimplex Group has been catapulted into the world league of appliance makers with its purchase of Hamilton Beach – a large manufacturer of electrical appliances. Here, chairman and Business & Finance ‘Man of the Year’ Martin Naughton speaks to Aileen O’Toole.

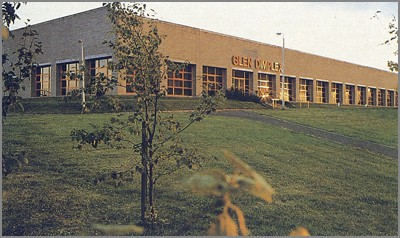

Glen Dimplex was still digesting Morphy Richards when that important telephone call came from New York. The UK’s market leader in toasters and irons was bought in 1985 by Glen Dimplex.

Glen Dimplex was still digesting Morphy Richards when that important telephone call came from New York. The UK’s market leader in toasters and irons was bought in 1985 by Glen Dimplex.

There was no plan to go for another large acquisition. “We got a call from a broker, who described himself as a typical New York middleman and he told us that Hamilton Beach (HB) could be available,” Naughton explains. “He said that the price would be over $100m, which was a frightening figure, but it was a once-in-a-lifetime chance.”

What is Hamilton Beach? (Naughton’s wife thought it was a hotel in Bermuda). Brand names have not travelled well in the electrical business; a list of the top dozen names in the American market includes just two or three names which would be recognised by consumers on this side of the Atlantic. HB is a strong brand in small appliances and over half of its annual $185m sales is composed of products which dominate their market niches. Included are knives, food processors, toasters, blenders, coffee-makers and corn-poppers; commercial versions of its drink mixers and blenders are visible in American bars and ice-cream parlours.

Glen Dimplex had considered American before but was conscious of the impossibility of entering that market with its own unknown brand names. “The big prize is America. Anyone in business has to think of America,” he says. There was just one problem: money. Initially daunted by the scale of HB, Naughton soon found that raising the finance would not be a problem. “Morgan Stanley told us at our first meeting that with our track record, there would be no problem financing the deal in America. They issued a highly confident letter that the funds would be provided − it is not exactly a legal commitment, but the bank is putting its reputation on the line,” he adds.

The highly confident letter, however, came with a price tag of $100,000. Morgan Stanley talked in terms of a menu of money and finally recommended that Glen Dimplex should fund its bid through a combination of high-yield subordinated debt (better known as junk bonds), bank debt and just $15m of its own resources.

There were three other bidders, one financial institution, and two companies in the American appliance business. There was in effect an auction and the highest offer was accepted. Naughton is reluctant to disclose how much he was prepared to bid: “That would be a bit like showing your hand after the poker game.”

The contract price was $103.5m but Glen Dimplex also undertook to take on debts bringing the total price to $120m. Having cleared the final audit in December, HB became a wholly owned subsidiary from January 1st.

It’s a quantum leap for us which makes us as big in North America as we are in Europe

The New York Times reacted to the news of the HB sale by saying that the Belzberg brothers had sold the gem in their crown. Through their vehicle First City of Vancouver, the acquisitive brothers had bought HB’s parent, Scoville. Why did they decide to divest themselves of HB, a business whose profit margins are an average of 9% to 10%? Newspaper columnists in The Wall Street Journal and elsewhere have speculated that the $523m price for Scoville was too high and that they were attempting to recoup some of it. Naughton is not overly concerned with the Belzbergs’ motives but is grateful to them for the chance to break into the US at the HB level.

Since the purchase was announced on October 9th, Naughton and deputy chairman Lochlann Quinn have been busy finalising the financial package. Apart from its own $15m, a line of credit of $80m was negotiated to make plenty of allowance for seasonal factors. Morgan Stanley aimed to raise $60m through the junk bond issue.

In mid-November, Naughton, Quinn, HB’s president John Flaherty and the team from Morgan Stanley did a coast-to-coast roadshow to sell the bonds to financial institutions. They started with a breakfast meeting in Chicago, where Naughton found the executives very well briefed on his background. A business columnist in that morning’s Chicago Sun-Times wrote the Glen Dimplex story under the heading: ‘A Yank success with an Irish twist’.

Within a week, the group repeated the exercise for financial institutions in Minneapolis, Pittsburg, Boston, San Diego, Los Angeles, Houston, New York and Baltimore. The itinerary was gruelling but the reaction was positive. “There was a lot of goodwill towards us,” he recalls. “With all the financial institutions it seemed the most natural thing in the world that an Irish company would try to raise funds like this in the States.”

As the roadshow hit New York, the second last stop, the Ivan Boesky insider trading scandal broke. With subpoenas being served on Drexel Burnham Lambert, the market leader in junk bonds, the glamour securities began to lose some of their glitter. Naughton, glad that he was dealing with Morgan Stanley, still felt some of the fall-out from the affair: “It had the impact of making people less bullish. Everyone was being more conservative and they were standing back.” Nonetheless, the issue was a success and was oversold by $5m. Glen Dimplex decided to take the $65m.

BONDS

The main advantage of these bonds to Glen Dimplex is that it does not have to use its existing assets, the various businesses in Europe, as security. The bonds however attract an interest rate of 13% compared with 8% for conventional borrowings. Naughton admits the HB is highly leveraged and estimates the annual interest bill to be around $10m. One of the first priorities will be to reduce the debt burden through efficient cashflow management, and an improvement in the current profits, which are already ahead of industry averages in the US.

Naughton is under no false illusions about the size of the task ahead: “It’s a challenge and a great opportunity. I’m relaxed about it. It’s a quantum leap for us which makes us as big in North America as we are in Europe.”

With all the financial institutions it seemed the most natural thing in the world that an Irish company would try to raise funds like this in the States

The purchase price represents a multiple of seven or eight times HB’s earnings, excluding the cost of the funding. “We think we’ve paid a high price for it but the earnings are good and we believe it is going to present tremendous opportunities. We’re not underestimating the workload involved. It will be a question of making two and two equalling five or six,” he predicts.

He wants John Flaherty and the other HB executives to continue to run the company, with minimal influence on day-to-day matters from the new Irish owners. Over the last few months he reckons he has “served his apprenticeship” by investing time in getting to know the company, its people and products.

There will be reporting packages and monthly board meetings, but he will not have to work out of HB headquarters in Waterbury, Connecticut. He can afford to distance himself because HB is sound: “If it was in trouble it would be arrogant in the extreme to think that we could run it from here.”

By contrast the Morphy Richards acquisition needed more attention − which it got for the best part of a year.

TRADING RECORD

Naughton is excited about what HB does now and the potential it holds when it can be “fused” with Glen Dimplex. HB’s trading record has been one of constant profitability, with 1986 operating profits expected to come in at $16.5m compared with $11.5m the previous year. That year’s trading was depressed by competitive pressures in the marketplace. Prices dropped following Black and Decker’s purchase of General Electric’s domestic small appliance business but through 1986 HB recovered, largely through good demand for its new products. Around 80% are sold under its own brand name and the remainder under private label.

Before the purchase, HB owned a 20% stake in Moulinex, the French appliance maker, and also has a joint venture to distribute Moulinex products in the US. Naughton decided not to bid for the Moulinex stake; he does not favour minority holdings. The shares are still held by the Belzbergs. The joint venture arrangement still stands and was responsible for sales of $6 million in 1986.

STRATEGIC GROWTH

STRATEGIC GROWTH

The HB deal is seen to make strategic sense. HB has certain strengths in motorised products like coffee makers and food processors, sectors which Glen Dimplex is not in.

Glen Dimplex, meanwhile, has been successful in products like toasters, irons, and towel rails from which HB can learn. Already there has been product swapping. “We just cannot take products from one company and stick the other’s name on them. The appliances have to be right for the market,” he says.

Future design work will take account of all markets and Naughton estimates that this synergy will be measured in tens of millions of pounds in the years ahead.

HB employs 1,700 people between its two manufacturing units in North Carolina and its headquarters. The acquisition swells Glen Dimplex’s total employment to over 4,000 of whom 1,200 work in Ireland. The company’s low profile is such that a 30% increase in Irish employment in 1986 occurred without the usual publicity which is attracted to any company which creates jobs. Next year Naughton predicts total employment for the group to be around 4,500.

The HB purchase will expand the group’s current year’s sales of £135m, without any HB contributions, to £300m for the year to March 1988. Naughton is coy on the subject of profits. Working on the same profit margin as HB, an estimate for Glen Dimplex’s profits for the year to next March would be over £12m.

To group’s private status assisted it in this deal, Naughton says: “If we were a public company we would not be able to move that quickly. We would have had to send in accountants to make sure that we would be accountable to our shareholders. We only have to be accountable to ourselves. We didn’t do too much agonising over it because on our first day in America we knew we could afford it.” Naughton owns 75% of the group, with the balance hailed by Quinn.

No interview with Martin Naughton is complete without the question about whether it is considering going public – there is a queue of stockbrokers and investment people who would like to see it going that route. “There is a certain inevitability about it as we grow larger,” he replies. “It may become necessary at some time. I am on record as saying that I’ll never say never again.”

With HB under his wing, is Martin Naughton satisfied with Glen Dimplex’s global spread? The big job ahead, he says, is to come to terms with HB and make the most of the marriage. “And I suppose that the next logical step for us would be a continental European manufacturer, a good German or French brand name. That would round the globe nicely for us.”

TURNOVER IS VANITY, PROFIT IS SANITY

Martin Naughton is a self-made man who does not believe in philosophising about the reasons for his success: “I don’t think that what I have done gives me the right to tell other people how to run their businesses or tell the government how to run the country. I look at some of the people who do that and then look at their businesses and I’m not overly impressed by them. It might be more profitable if they concentrated on their own affairs.”

He declined invitations to speak at conferences and to join the councils of honorary groups. He made an exception for the Institute of Industrial Engineers and describes himself as “the worst president they’ve ever had”. His affinity with the Institute is explained by the fact that his first job was as an engineer, or a works study engineer as it was then.

I don’t think that what I have done gives me the right to tell other people how to run their businesses or tell the government how to run the country

Naughton was Dublin born, but reared and schooled in Dundalk. He had just turned 16 when he completed his Leaving Certificate. In the latter part of the ‘50s career opportunities in Ireland were limited to the banks and the civil service, neither of which appealed to him. He went to England and served a five-year apprenticeship as an aeronautical engineer with Hawker Siddley.

He was offered a job as a second engineer on a luxury Caribbean cruise liner. “Then there was one of those quirks of fate. I met a guy from Ireland on a busy Saturday afternoon in Southampton and he told me about a job advertised in the Daily Telegraph in Shannon Airport. I wasn’t very interested, but I met the same guy in the same place the following Saturday and he gave me the ad from the newspaper. He had gone to so much trouble that I decided to apply.”

He was called to the first interview and thought it will be “no harm” to take advantage of the all-expenses paid trip to London. The second interview entailed an all-expenses paid trip to Shannon, but at this stage Naughton was more interested in the job as a work-study engineer with SPS International. He got the job. Why did he turn down a rare chance to see the world from a luxury liner? “It was the opportunity to come home. I had always intended to come back to Ireland.”

CAREER PATH

CAREER PATH

Within months he was nearer to his hometown of Dundalk, when he moved to an AET in Dunleer as the chief works study engineer. It was 1962 and AET was Ireland’s leading domestic appliance manufacturer and at its peak employed around 1,200 people. With the exception of a year-long break, when he moved back to Shannon to work for a breakaway company of SPS, he spent the next 11 years in AET. He was promoted to production manager and then works manager.

Then the tide began to turn for AET, which had developed in protected markets. The lifting of trade barriers brought fresh competition and plunged AET into losses. Foir Teo got involved and the priority, according to Naughton, was to “sustain employment at all costs”. He felt that AET would continue to report losses of £1m a year if it was pursued that policy and drew up an alternative plan. “I wanted complete cutbacks to get the company back to rock base and then rebuild it from there.” It was rejected.

Frustrated and despondent, Naughton decided to amend his rescue blueprint and turn it into a business plan for a greenfield project. He set up Glen Electric in Newry in 1973 by accumulating and borrowing as much money as he could − £60,000 in fact. The sum was matched by the Northern Ireland Finance Corporation (NIFC). In general, the agencies there were supportive and had no misgivings about the future of a new venture which was to make electric heaters at the start of oil crisis.

Money was tight. “Meeting the payroll on Fridays became the priority in life,” he says. The skills that he, and four other ex-AET people, had were product-related: “We had a full-time design director but we didn’t have an accountant.”

Profitability is what we’re looking at all the time. We’re not looking at turnover or marketshare

Accounting services were supplied through Arthur Anderson by Lochlann Quinn, who is now Glen Dimplex’s deputy chairman and 25% shareholder. The first year’s sales targets were comfortably broken and Glen turned in a profit, as it has in every succeeding year. Shares issued to NIFC were bought back and “from that point on we’ve used our own resources”. The first of the string of acquisitions was Dimplex, the prestige name in the electric heating business in the UK, and five times Glen’s size.

Then came the acquisition of the AET factory, which had suffered the fate, which Naughton had predicted. Belling’s heating business, Westinghouse’s shaver socket subsidiary, Burco Dean’s built-in cookers and hobs, electric blanket manufacturer Blanella, and Morphy Richards (reckoned to be the UK’s best-known maker of small appliances) were added.

Each time Naughton says that Glen Dimplex has had few problems raising the finance − the purchase prices for the majority of the group’s 10 acquisitions to date have never been disclosed.

Profits have been ploughed back into the business. The group’s track record is good, he maintains, and it is tightly run with a head office team of just five: “Profitability is what we’re looking at all the time. We’re not looking at turnover or marketshare. I think the only bit I ever cut from a newspaper was something I saw in the financial times that turnover is vanity, but profit is sanity.”

P ERSONAL INTERESTS

ERSONAL INTERESTS

Naughton is a relaxed individual who sees his role as looking after people, employees and customers, and products. “Apart from that I do very little,” he jokes. He has good relations with his managers: “I think we should enjoy our jobs. We don’t have shouting matches − life’s not worth that.”

While he may be quick to buy companies, he is slow to select people to run them. The management team is “given a lot of responsibility and a lot of autonomy to make their own decisions”, but they are “very highly rewarded to deliver on budget”.

He admits to having “no real hobbies except for a lot of hard work”. The spread of his business interests means that he is abroad every week of the year. Any spare time he has he prefers to conserve it for his home life in Castlebellingham. He has no ambitions that his three children, all school-going at the moment, should follow him into the business. “I’m not creating a dynasty here,” he says.

The HB deal has brought Glen Dimplex, and Martin Naughton, into the limelight: “We put out a press release on it and it was like a volcano took off. Some of the questions brought out how little-known we are. I now hope to go back into the shell if I possibly can.”

SETTING THE SCENE – 1987

Naughton’s rising fortunes in the 1980s occurred during an era of political instability and corruption, with power alternating between Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.

The problems were beginning to be dealt with in 1987 under a minority Fianna Fáil government – led by Charles Haughey – with assistance from Alan Duke of Fine Gael under what became known as the ‘Tallaght Strategy’, with economic reform, tax cuts, welfare reform and a reduction in borrowing to fund spending.

1987 holds many notable fond memories for the Irish public. Johnny Logan won the Eurovision Song Contest for Ireland with ‘Hold Me Now’, making him the only person to have won the competition twice as a performer; cyclist Stephen Roche was victorious in the historic Tour de France, and U2 released the iconic The Joshua Tree album. Also in 1987, voters went to the polls in the referendum on the Single European Act (70% voted in favour of the amendment); Beaumont Hospital opened its doors and Roddy Doyle’s The Commitments was first published.