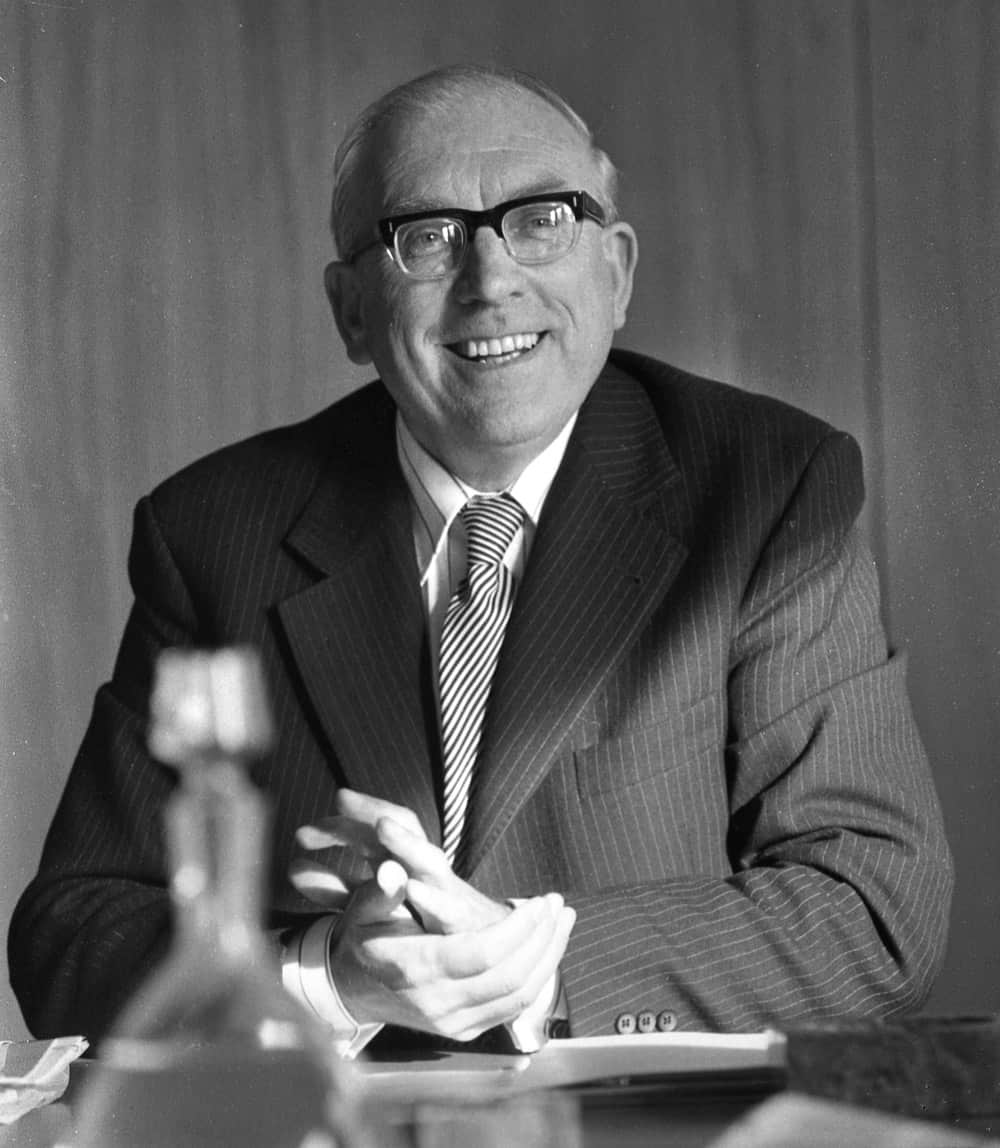

As TK Whitaker celebrates 100 years – and ahead of the inaugural TK Whitaker Award for Outstanding Contribution to Public Life being awarded to Michael D Higgins at next week’s Business & Finance Awards – his biographer Anne Chambers reviews the career of the 1976 Business & Finance Man of the Year.

In the midst of the centenary commemorations for the 1916 Rising, it is fitting to recall that 1916 also commemorates the centenary birth of another patriot who led a revolution of another kind in the economic, financial, social, educational, political and cultural evolution of the country.

Born in 1916 in Rostrevor, Co. Down, Ken Whitaker’s family moved south to Drogheda where at the local Christian Brothers school his potential was first nurtured. In 1934 his footsteps led him to a career in the civil service, entering at the basic clerical officer grade. There his talent broke through predictive promotional convention and his record rise through the ranks, unequalled to this day, saw him become Secretary of the Department of Finance in 1956 at 39 years of age.

Against a background of economic stagnation, rampant emigration, lack of entrepreneurial spirit and an atmosphere of national despondency, with a band of willing young acolytes he devised Economic Development, a blueprint for the economic regeneration of the country.

Detailed, meticulous and practical, written in a style and in a language aimed at the ordinary citizen as much as at politicians, Economic Development offered a radical remedy: the replacement of non-productive by productive capital expenditure, the introduction of free trade and an end to the isolation and protectionism of the previous era.

It lowered the barriers that Ireland had erected around itself and allowed the Irish people to look at their country not from some mystic, historically idealised vantage point, but from eye level. But above all, Economic Development offered hope and a way out of the economic quagmire in which Ireland and its people were fastbound.

Economic Development was devised on a totally voluntary basis, with Ken Whitaker and his team working outside office hours on their own time, without any notion or expectation of monetary or promotional recompense, a civic-mindedness that somehow seems anachronistic in this age of entitlement, top-ups and bonuses.

A LASTING LEGACY

Biographer Anne Chambers and TK Whitaker

As secretary of the Department of Finance, Ken Whitaker left his imprint in other ways. In 1957, he helped to establish the Institute of Public Administration to cater for the training needs of the public sector and introduced a public sector university scholarship system.

Economic Development offered hope and a way out of the economic quagmire

To rectify the shortcomings in economic research, he personally elicited a grant from the Ford Foundation in America to establish the Economic and Social Research Institute in 1960.

During the 1960s, Ken Whitaker spearheaded Ireland’s convoluted path towards membership of the European Economic Community, leading delegations to European capitals, culminating with a private meeting in 1967 with the implacable Charles de Gaulle.

His later unease that the idealism, realism, community ethos and élan vital that motivated the community’s founding fathers and were enshrined in the Treaty of Rome, were being sidelined has a certain resonance today. Regarding the European Monetary System, it is also interesting to note Whitaker’s less than enthusiastic reaction to Ireland’s abandonment of sterling in 1979, a move that he then, perhaps prophetically, described as ‘a quixotic gesture’.

In 1969, Ken Whitaker was appointed governor of the Central Bank. On his appointment he gave public notice that the bank would be ‘the warning light’ and that it might also have ‘unpalatable things’ to say. Under his governorship the Bank was transformed into a dynamic and effective institution, which he guided with a firm hand through many economic and financial upheavals at home and abroad.

From the start, he set out to ensure the autonomy of the Central Bank vis-à-vis the government, the Department of Finance and the commercial banking sector. In 1970, he successfully resisted efforts by the Department of Finance to obtain statutory control over the exercise of credit policy, a move that, as he noted at the time, he “could not regard as being in the national interest”.

His words to the Minister for Finance that “as a good Catholic I recognise the supreme authority of the Pope, but like a good bishop I claim jurisdiction within my own diocese”, were followed by his ultimatum that if the minister persisted, he would resign as governor.

In the 1970s against a background of runaway inflation, balance of payments deficits, galloping current and capital expenditure and irrational pay awards, he enforced strict credit constraints over the commercial banks, restricting credit to productive purposes with penalties for increases in gross lending to the over-heating property sector, as well as stemming the tide of external capital inflows.

He resisted numerous government attempts to fund budgetary concessions for non-productive purposes out of the coffers of the Central Bank and, both privately and in public, gave forceful advice on economic and financial policy before it was enacted, thus preventing even greater excess. In the area of regulation and supervision, under Ken Whitaker’s governorship, the Central Bank’s control over the Irish banks evolved and strengthened.

In more recent times the failure of that warning light to flash in Dame St. during the reckless credit-creating years of the Celtic Tiger left him perplexed and appalled. His choice of words in 2011 to the new governor, Patrick Honohan – “I’m counting on you to save the country from national humiliation” – expressed the depth of his disappointment at the Central Bank’s perceived failure to discharge its obligations.

While Ken Whitaker is the first to acknowledge the immense changes that have revolutionised the banking sector, it is difficult to imagine that under his stewardship the warning light would not have been flashing in Dame St. long before the banking collapse occurred, or that he would have agreed to the decision to separate the supervisory and regulatory functions from the Central Bank.

And during the so-called Celtic Tiger debacle, while a diminution in the bank’s authority may well have been the result of European Central Bank intervention, the Irish Central Bank retained sufficient authority nationally to curb the doubling of house prices, the tripling of credit to the building industry and the sanctioning of loans up to and beyond 100% that occurred.

And during the so-called Celtic Tiger debacle, while a diminution in the bank’s authority may well have been the result of European Central Bank intervention, the Irish Central Bank retained sufficient authority nationally to curb the doubling of house prices, the tripling of credit to the building industry and the sanctioning of loans up to and beyond 100% that occurred.

And with Ken Whitaker on the board of the ECB, Jean-Claude Trichet would have been faced with a more determined opponent to his policy of light-touch regulation leading, as it did, to the inadequate and incompetent supervision of the Irish banking system and to Ireland’s subsequent ‘humiliation’.

RETIREMENT?

In 1976, Ken Whitaker resigned from public office… or thought he did. But his services to the state, if anything, increased – from the Senate, where he is unique in being nominated by two major political parties while speaking as an independent, to the Council of State, to his 20-year enlightened chancellorship of the National University of Ireland. On a voluntary basis his wise counsel and ability steered a range of public commissions and committees, from penal reform and fishery policy to constitutional review – all combined with his chairmanship of some 40 public bodies.

Between 1967 and 1997 he played a seminal behind-the-scenes role in the search for peace in Northern Ireland. From initiating cross-border relationships as early as the 1950s with his civil service counterparts in the North on issues of mutual cross-border benefit, such as electricity supply, transport and the Erne Waterway, to arranging the historic meeting between Sean Lemass and Captain Terence O’Neill in Stormont in January 1965, despite the chaos of the following decades he never gave up on the search for peace by constitutional means.

In 1969, amidst the carnage, rioting and teargas, he wrote Jack Lynch’s famous ‘Tralee Speech’ that publicly, and for the first time, committed the Irish government to a policy of reunification by the principle of consent.

In 1970, he embarked on a dialogue with his opposite numbers in the public service and banking sectors in Northern Ireland and the UK, from which emanated many policy documents which, in turn, informed the Irish and UK government’s policy on Northern Ireland. One of his own policy documents, ‘Northern Ireland – A Possible Solution’, written in 1971, is in reality the Good Friday Agreement for slow learners.

Another motivation in Ken’s life is his love and commitment to the Irish language and, in this, his approach was again one of practical application: from his promotion of bilingualism as a national policy rather than the more impractical replacement of English by Irish, to his enlightened chairmanship of Bord na Gaelige, he left his mark.

Eamon de Valera, Terence O’Neill and TK Whitaker

In Ken Whitaker, we are reminded of what is best in all of us, both as a society and as individual citizens. Now in his hundredth year, his sense of hope, his generosity and good humour continue to burn brightly as each day brings a new interest and a new challenge. He remains sanguine about reputation, noting that “if you live long enough you would be either canonised or found out, the worst fate being found out after you are canonised!”

He set out to ensure the autonomy of the Central Bank vis-à-vis the government

During the course of writing his biography it became clear why the ordinary citizens of this country choose to confer the accolade Irishman of the 20th Century on this former public servant.

For as the so-called icons of Irish society, one by one, fell from their pedestals, as tribunals, trials and inquiries revealed the shortcomings of those entrusted with the care of the country and the welfare of its people, as greed and corruption became the hallmarks of success in Irish society, as the two state institutions over which he once presided failed in their duty of care to prevent the loss of Ireland’s economic independence, consigning generations to a future of indebtedness, the people’s choice of TK Whitaker as Irishman of the 20th Century seems now, in 2016, more than ever vindicated.

About the author: Anne Chambers is author of TK Whitaker: Portrait of a Patriot (Doubleday Ireland).

President of Ireland Michael D Higgins is to be honoured with the inaugural TK Whitaker Award for Outstanding Contribution to Public Life at the Business & Finance Awards ceremony at The Convention Centre on December 15th.

2017 WHITAKER LECTURE

As TK Whitaker turns 100 years old, the Central Bank has announced that the 2017 Whitaker Lecture will be delivered by professor Frances Ruane and that TK Whitaker’s papers will be available in the new Central Bank archive opening at its new offices in Spring 2017.

The Central Bank established the Whitaker Lecture as a flagship lecture series which takes place every two years.

TK Whitaker served as governor of the Central Bank from 1969 to 1976: a fascinating period for the Irish economy.