In Xintang, where the economy is centered around textile production, Greenpeace has found high levels of industrial pollution and has documented the effects on the community. ©Lu Guang/Greenpeace

Mark Godfrey warns that China’s big plans to target pollution will make manufacturing here a lot more expensive.

There’s been a lot of talk about wage inflation in China rubbing out much of the country’s once-formidable competitiveness in manufacturing.

Factory wages are still rising at an average 10% a year in China, counting inflation, yet there’s another inflation that’s about to make business here more expensive, and that’s energy.

Electricity prices are set to increase significantly to pay for pollution, and having adopted a develop-now-fix-environment-later approach to economic growth, China is paying a price for pollution much sooner and more expensively than it had anticipated.

A few days of severe smog in January 2013 and a collapse in tourist numbers last summer, were enough cause for extreme alarm in the wealthy enclaves of Beijing where Communist Party officials and executives live.

Closing and retrofitting a swathe of coal fired power plants is Beijing’s ambitious answer to pollution levels in Beijing, which frequently exceed by 40 times the recommended World Health Organisation limits.

Pollution

The model which made China prosperous is now being ditched as a wealthier population demands an end to pollution previously accepted as an inevitable side effect of factory-driven development. Coal-fired heating and electricity is blamed for a quarter of the pollution choking Beijing and cars account for another quarter of the problem according to energy consultants IHS.

More than 70% of China’s 4,937 terrawatt hours generated in 2012 came from coal. Under an urgent-sounding government plan published in September that figure is supposed to drop to 52% within 10 years.

Regional coal-fired power plants contribute another 25% of Beijing’s smog woes. That means coal fired plants like Keliyuan, Shijingshan and Huohua in neighbouring Hebei province have all been told to cut emissions by modernising. But these plants provide power to factories in huge industrial estates in Hebei province and the port city of Tianjin. Someone’s going to have to pay the billions required to fix the power plants.

Given the world emissions trading system set up under the Kyoto accord is largely ineffective (carbon trading tariffs aren’t attractive enough for investors to make it worthwhile to fund retrofitting of Chinese coal plants), it’s looking like costs will have to be passed onto the end user, including the Chinese factory owner.

Rising tariffs

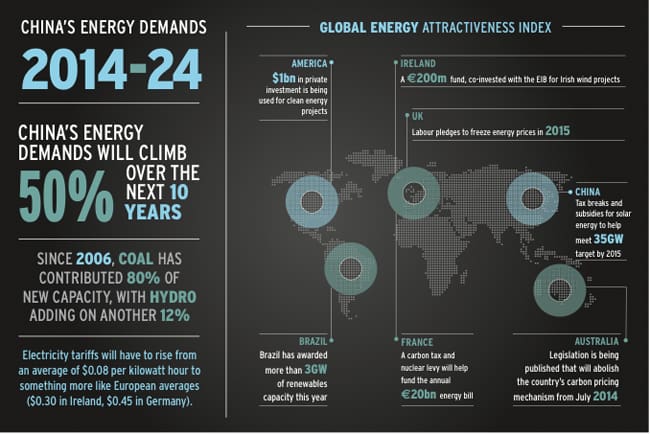

That means electricity tariffs will have to rise from an average of $0.08 per kilowatt hour to something more like European averages ($0.30 in Ireland, $0.45 in Germany). One of the reasons China is choking on coal is it’s cheap – about half the price of gas-fired power- and the state-run electricity sector has avoided raising prices by using the cheapest fuel. Since 2006, coal has contributed 80% of new capacity, with hydro tacking on another 12%.

To placate its new middle class, China is having to clean its coal plants, fast. Before last year’s apocalyptical smog, China was charting a more sophisticated, long-term solution to pollution which would also provide the country with a whole new industry.

China drew attention with ground-breaking clean-coal power plants like the GreenGen project in Tianjin. Alas, that zero-emission power generator has been making huge losses and hence doesn’t feature so much in the state media anymore, though obviously the lessons learned there in scrubbing coal are going to be useful.

Technology like this was being sold five years ago as a pain-free, scaleable and sale-able solution for pollution. This was supposed to be China’s way of innovating and dominating new technological solutions to pollution.

But while China still has the opportunity to become a world leader in clean coal and nuclear power technology, in a recently tighter budgetary situation Beijing will have to spread some of the pain and lift subsidies which have kept electricity relatively cheap.

Energy demands

Urbanisation means China’s demand for energy is going to climb 50% over the next 10 years; the bulk of that is happening in the east coast clusters that account for 51% of China’s GDP.

Of course there’s also the chance that dirty manufacturing gets moved inland. But that will only delay the inevitable of higher energy prices, and thus higher manufacturing costs, in China. Having gotten used to affordably-made-in-China TV sets and clothes, Western brands and consumers are going to have to get used to paying a higher China price. There’s no backing out of this for the government here.

This being a Leninist political system, there’s plenty of national plans and targets that don’t always make it to fruition. But this one is likely to be implemented. Because trust in government is very low, policy makers in Beijing have taken the unusual step of allowing publication of pollution data. The public availability of data measuring smog means the government will have to act.

A wealthier population demands an end to pollution previously accepted as an inevitable side effect of factory-driven development.”

Making the switch

Anyone in the business of retrofitting power plants is making a killing in China. Companies like LP Amina and Siemens have been struggling to meet all the work coming their way since Beijing started to get serious about clearing the air following some horrendous smog last year.

There’s plenty more to go: notoriously leaky refineries here have to switch to higher standards, for instance. And all of this will be done, not just because of the ability of an authoritarian system to effect change, but because China can’t afford to suppress the real price of energy and pollution in order to deliver economic growth.

Marketisation of utilities prices, announced in a batch of reforms last November, will also facilitate rises in China’s state-controlled energy prices.

Credible economists here have often claimed that China’s GDP growth would actually be in the negative if the real cost of utilities and the cost of environmental degradation caused by the country’s factory-driven development model were counted.

Now that China is about to count those costs, and to pay the cost of pollution, doing business here will get a lot more expensive.