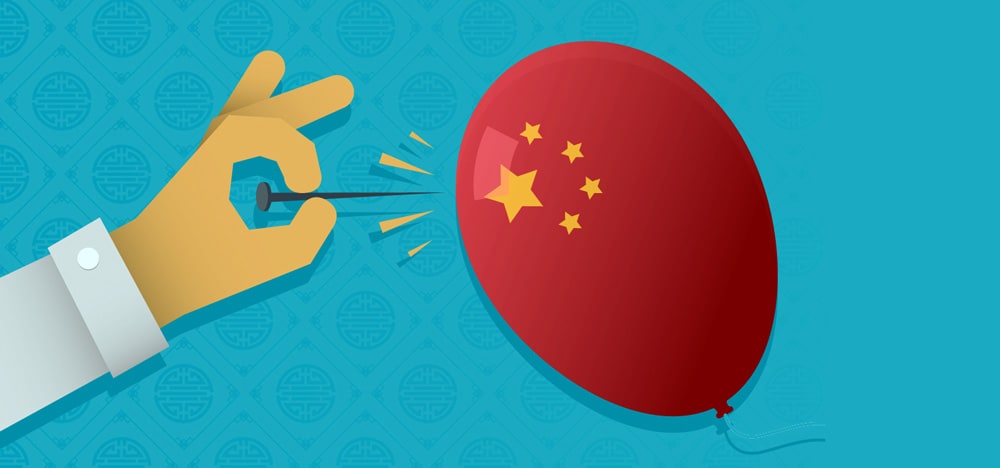

China’s reform conundrum is hurting business, writes Mark Godfrey.

Who’d want to be a banker at one of China’s state-owned banks these days? The likes of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) are often touted as the world’s biggest lenders (based on assets, not profits) but the past year has been stressful.

Anti-corruption inspections – still ongoing under the Xi Jinping presidency – and calls from local officials directing credit for local pet projects are all in a day’s work for executives at ICBC and other banks over the past year.

Yet at the same time they’re expected to be getting ready for the twin liberalisation of the banking market and the liberalisation of Chinese currency controls, which will bring interest rate reform and the end of guaranteed profits for state owned banks.

China’s banking sector is gradually being exposed to competition and companies who need to raise money are getting other options like internet platforms and a promised opening up of the corporate bond market. But over-extended banks are holding highly inflated assets and in the event of a sharper economic slowdown there will be an inevitable spiralling of bad debt.

This should be seen in the context of the country’s enormous corporate debt – the IMF puts Chinese corporate debt at 145% of GDP – which understandably makes investors fearful of investing, putting pressure on the yuan as money exits China. The fact that private sector investment grew by only 2.3% in the first half of the year shows that businesses in China are worried about economic prospects.

OPENING UP SERVICES

Businesses remain understandably cagey about the real direction of the Chinese economy, particularly since in 2015 GDP growth slowed to a 25-year low while the stock market fell 50% in value. Data for the second quarter of 2016 showed that China’s economy is stabilising, but some of that pickup is attributable to government lending and stimulus, which isn’t sustainable given broader debt problems in China’s banking and corporate sector.

Hence, for the past two years – and while fighting corruption among its ranks – China’s Communist Party keeps vowing serious ‘supply-side’ economic reform that would see the private sector liberated by the opening up of financial services and utilities price reform.

The country’s enormous corporate debt makes investors fearful of investing

This requires the defenestration of the hitherto highly influential state-owned enterprises and will mean the closing of lots of zombie companies in sectors like steel and manufacturing that have long survived on government supports and soft loans.

The prospect of mass layoffs – and the inevitable social and political problems – has always tempered the reform ambitions of China’s one-party state. However, government (which is after all the regulator as well as the key player/owner in some of the most profitable sectors controlled by state-owned firms) is unwilling or unable to ultimately deliver on promised market reforms, including numerous pledges to open up swathes of the economy controlled by state enterprises like ICBC, China Mobile and China Petroleum/Sinopec.

Private competition in banking alongside the liberalisation of interest rates and concomitant liberalisation of currency controls (which China has promised to complete by 2020) could mean that private business, which tends to be more profitable and less capital-intensive, will surge ahead – creating a whole new burst of economic growth for China.

But loss of privilege at state companies – and loss of jobs with the closure of zombie, unprofitable units – is tempering the reform ambitions of the party cadres, at least in the short term. In the longer run, however, the cadres’ feet may be held to the fire because of China’s debt situation.

China’s Communist Party keeps vowing serious ‘supply-side’ economic reform that would see the private sector liberated by the opening up of financial services and utilities price reform

Overall debt across the economy stands at 200-250% according to various informed estimates and that is causing worries and wobbles among the global investment community about the fate of China’s economy.

That in turn is feeding into downward pressure on the country’s currency. Beijing has spent around €500bn of its currency reserves defending the yuan since last summer’s badly planned intervention by the People’s Bank of China to reform the country’s method for setting the value of the currency.

In this scenario Beijing hasn’t got the luxury of deferring a fix for the structural issues in the economy and some massive redundancies may be imminent, which will have a hard impact on wage growth and consumer sentiment – if the private sector isn’t able to replace those jobs removed with the closure of zombie state-owned companies.

LACK OF STABILITY

All of this will decide the fate of the RMB, which China has vowed to defend in order to prevent outflows of cash by nervous businesses and the middle class. Most investment bankers are betting on a major devaluation of the yuan/RMB. Questions over the stability of China’s economy have prompted pressure on the country’s currency, with government expending nearly €600bn in currency reserves to defend its value over the past year.

The spectre of a sizeable devaluation remains, with government introducing a slew of policies in recent months to coax corporates to bring cash back from abroad in exchange for RMB.

China’s debt stands at 200-250% and that is causing worries and wobbles among the global investment community

Incredibly, the RMB in the early 1980s was pegged at 2.46 to the dollar, rising at one point to 1.50 to the dollar but then dropping sharply by 1994 to 8.62 as China sought to boost its export competitiveness. It was revalued in 2005 to 8.11, but now stands at 6.5.

Its central bank manages the RMB’s appreciation or depreciation as it sees fit but limits its fluctuations to within 2% of the dollar.

China ultimately wants to be able to settle international transactions in its own currency, which is still only convertible on the current account for trade, not on the capital account, which is for investment and banking flows. If and when the gates are fully opened there will be even more stress for state-owned bankers.