Marc Coleman, economist and founder of Octavian Consulting, discusses the projected impact of Covid-19 on the corporate sector

The first rule of business is “don’t run out of cash.” For government, with the ability to raise taxes, it looks like less of a constraint. But given both the unemployment figures and latest set of Exchequer returns released this week, the economy’s ability to yield taxation is strained.

On the face of it, the figures weren’t too bad. In the year to May the total tax take, some €21.7 billion, was steady compared to the same period of 2019. Looking closer, it is evident that the figures are greatly affected by corporation tax receipts.

Up from €1.8 billion in the year to May 2019, to almost €3.5 billion in the same period this year, the government’s finances are still benefiting from the lagged impact of strong corporate results generated mostly last year and early this year year. In November, when approximately one third of all corporation tax revenues are received, the impact of Covid-19 on the corporate sector will kick in more fully.

Any government that attempts to raise taxes before fundamentally addressing issues of fairness and priority on public spending is less likely to endure than one that does the reverse

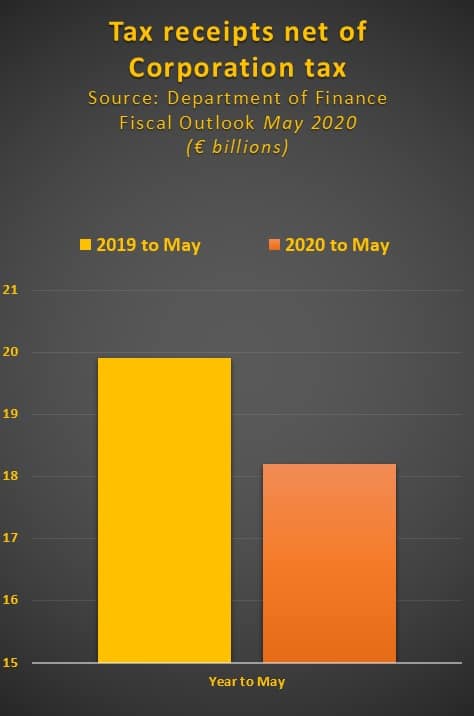

Adjusting for this impact, a truer picture of the tax revenue position is as follows:

Net of corporation tax receipts, tax receipts fell from €19.9 billion in the year to May 2019 to €18.2 billion in the same period this year. This fall, of 8.5 per cent, still flatters somewhat in that it includes the lagged impact of income and capital tax receipts.

A more most accurate bell weather of the economy, VAT receipts for the year to May, are still somewhat flattering in that approximately half of this period (January to mid-March) was unaffected by Covid-19. For this period VAT receipts fell from €7.3 billion for the relevant period of 2019 to €5.7 billion now. That decline, 21.9 per cent, gathered pace in the month of May when receipts were down by over one-third (35.4 per cent) year-on-year. The slower the lockdown ends, the slower performance in this and other tax heads will resume. And the fewer number of businesses will make it back afterwards: Longer lockdowns lead to more asymmetric impacts with a higher rate of attrition, particularly amongst small businesses.

As VAT slowly recovers the performance of other tax heads where the impact of Covid-19 is more lagged will converge resulting in a year-on-year revenues loss that, in my estimation, will be somewhere between 20 and 30 per cent (€12 billion to €18 billion) for the full year. While this writer doesn’t like to be pessimistic (and has a track record of optimism). But on this occasion several facts point to a more pessimistic outlook:

Firstly, we still are only witnessing “first-round” tax revenue impacts on government finances, namely the largely domestic impact of the lockdown. “Second-round” impacts of a decline in global trade, impacting on corporation tax and income tax receipts and “third-round” impacts on financial, asset and property markets, impacting on capital taxation, have yet to fully impact.

Before we indulge in a narrative that favours the Nordification of our tax system, the fairness productivity and meritocracy of public expenditure and reform must first be examined prior to any change in tax policies

For those reasons I am less optimistic than the Department and suggesting a range of €12 to €18 billion for the revenue loss this year (the ESRI, which published forecasts in the last fortnight, has also become more concerned). Its worth noting that the middle of this range, €15 billion, is broadly equivalent to the entire tax revenue loss between 2008 and 2010 inclusive during the last recession.

The policy implications are so obvious one doesn’t need a PhD – nor even an economics degree – to spot them:

Firstly, Tax receipts in November – which typically accounts for one sixth of receipts for the full year (due to corporation tax, self-employed income tax and VAT payment cycles) – will be absolutely critical.

Secondly, and due to the directly aforementioned factor, the performance of the economy the July-October period will be decisive.

Thirdly – and for the first and second reasons above – and even if the assumptions underlying it require updating, the case made in “An Economic Response to Covid-19,” for a budget in June-July to signal confidence and demand in the second half of the year (followed by a housing specific budget in the autumn) is as strong as ever.

Fourthly, digital taxation and the tax base generally will need to be examined. But before we indulge in a narrative that favours the Nordification of our tax system, the fairness productivity and meritocracy of public expenditure and reform must first be examined prior to any change in tax policies. This is because of the fifth implication: A government must not only be formed, but must last for at least 18 months to deliver us through the crisis and into an ensuing recovery period. And any government that attempts to raise taxes before fundamentally addressing issues of fairness and priority on public spending is less likely to endure than one that does the reverse.