Marc Coleman is Founder of Octavian Research and Public Affairs consultancy. In this guest post, he writes that tax rate hikes may be the wrong answer to government’s difficult fiscal position.

An exchequer deficit of €9,452 million was recorded in the year to end August 2020 a rise of €8,827 million over the €625 million deficit recorded in 2019.

The revenue performance looks steady under the circumstances, down just 2.3 per cent on the same period of comparison. But this appearance is deceptive, for two reasons:

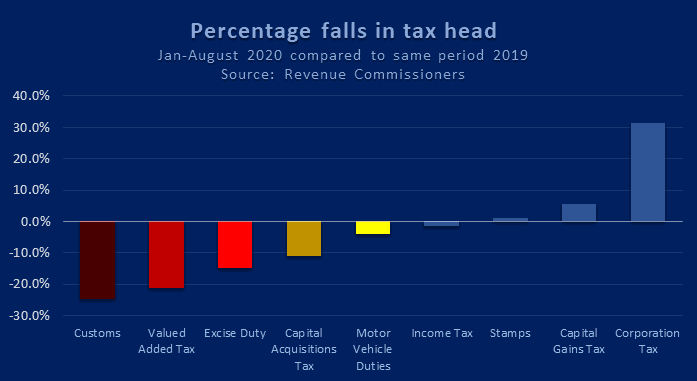

Firstly, corporation tax receipts for the cumulative period are 31.4 per cent ahead of schedule. This reflects the lagged effect of very strong multinational profits in 2019. Exchequer figures are a cash rather than an accrual based reporting system (last October Minister for Finance, Paschal Donohoe, did announce the intention to move reporting to an accruals basis, but this has not yet occurred – presumably interrupted by COVID-19. Excluding corporation tax receipts, the tax take in the year to August was 7.8 per cent lower than a year before.

Secondly, the significant injection to the economy from measures taken in early spring (including the Temporary Wage Subsidy Scheme and Pandemic Unemployment Payment) are so far working to mitigate what might have been a far worse performance in other tax heads. Income tax receipts in particular are benefiting from this, but at the cost of a rising level of national debt the sustainability of which cannot be assumed indefinitely.

The chart below suggests a strong positive correlation between the length of time it takes for changes in economic activity to filter through to exchequer cash receipts on one hand and, on the other, the rate of change in revenue receipts, with Corporation and Capital Gains Tax continuing to perform well while Customs, VAT and Excise Duties perform poorly. Clearly, profitability in several sectors collapsed in the second quarter of this year and will not recovery until at least next year.

From Q3 onwards, this impact will begin to dissipate as corporation tax receipts decline. Furthermore, unlike income taxes, corporation tax liabilities can be negative as corporations write losses off against positive liabilities. As strongly as they assisted the overall exchequer situation in 2020 – and for the same reason – corporation tax receipts are for this reason likely to drag down performance in 2021. Weaker corporate borrowing in the second quarter and a shift from long-term to short-term credit – as evidenced by the Central Bank’s latest Quarterly Bulletin – also points to weaker corporate investment and profitability next year, at least in the domestic economy that needs it most.

As this begins to happen – from Q2 of next year onwards – a separate impact will depress other tax heads: The ending of the Employer Wage Subsidy Scheme after 31st March next. This is because the relatively closed nature of the domestic economy this year and lack of foreign travel may have increased the domestic “multiplier” – the rate at which domestic spending circulates within the economy, thereby giving the government a tax return on its pandemic support expenditure.

The timing of the ending of a major component of that as Q2 2021 begins will thus withdraw a key support for the domestic tax take just as the multinational dominated corporate sector’s contribution is beginning to reverse itself.

This all points to a budgetary dilemma this October: How to control the size of the budget deficit without strangling the economy with higher tax rates? Alternatives – such as public sector economising and reform – are unlikely to happen at a time when the government is highly dependent on public service provision and fearful of antagonising strong representative interests upon which it so clearly depends.

Despite being far more numerous, taxpayers are politically weaker due to their lack of identity and diffused nature of interests. With an election at least 4 years away, they also have no effective voice.

Political realities, therefore, point to further increases in tax rates in the next budget with depressing effects on domestic demand, employment and investment in 2021.

Nor is it clear that these tax hikes will even generate additional exchequer revenue. A debate is certainly needed about taxation and the Programme for Government provides for a commission on the matter. But one thing is clear: Any attempts to promote tax increases without a fundamental review of how the public sector operates could do irrevocable damage to our political system. To create the right conditions for further tax increases – never mind the public sector pay rises that will be funded by them – more openness, meritocracy and efficiency will have to be delivered beforehand. Otherwise, Golfgate could pale into comparison to the political impact of Budget 2021.

Finally it is merciful news that only 14 people died during August, and that the rate of deaths each week fell from 9 in the first week to last week. The rate of monthly fatalities from Covid-19 is now well below the rate of death by suicide of approximately 35 persons per month as based on the latest Vital Statistics data released last May by the CSO. This is a sad reminder that deaths from the virus are not the only tragic consequence of COVID-19: The economic impact lockdown has irrevocably and detrimentally scarred the lives of hundreds of thousands of people in ways that – while they may express sympathise with – those on the NPHET are ill equipped to comprehend.

Marc Coleman is Founder of Octavian Research and Public Affairs consultancy and his latest book “An Economic Response to Covid-19” is available on www.octavian.ie. He is also a former ECB Economist, Irish Times Economics Editor and senior manager with Ibec.