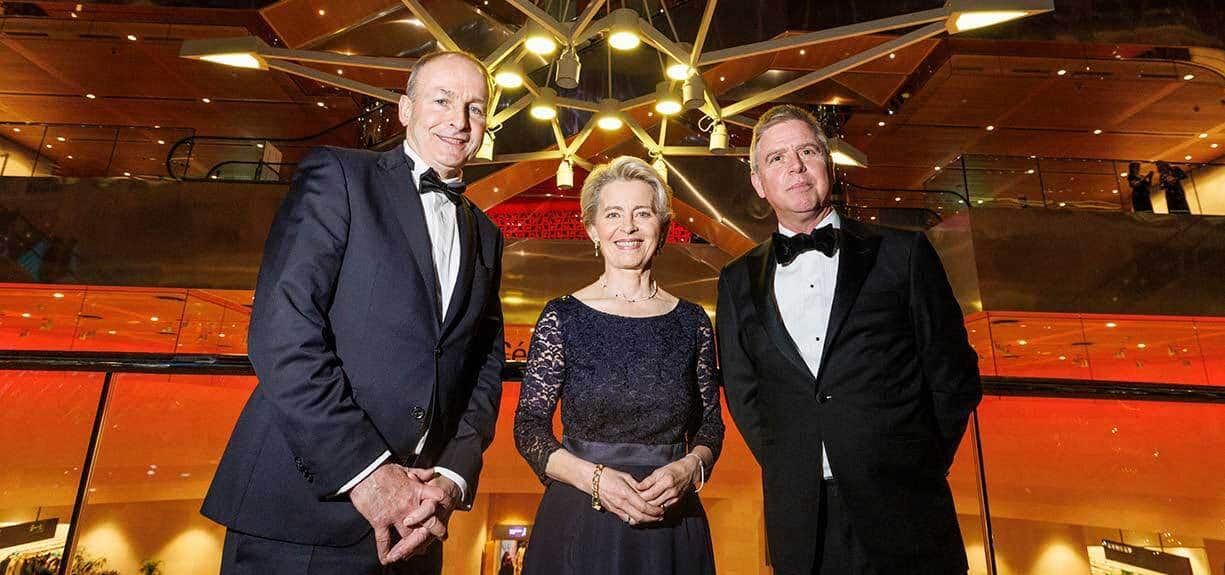

Pictured (from L–R): An Taoiseach Micheál Martin, European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen and Ian Hyland, President and Publisher of Business & Finance. Picture by Andres Poveda.

Ireland-EU at 50 book published by Quartet Books, Business & Finance and edited by John Walsh, marking fifty years since Ireland’s accession to the European Union.

Ireland-EU at 50 book published by Quartet Books, Business & Finance and edited by John Walsh, marking fifty years since Ireland’s accession to the European Union.

Ireland EU at 50 is a collection of contributions including Frances Ruane, David O’Sullivan, Francis Jacobs, Brian Hayes, Marian Harkin, Danny McCoy, Kieran McQuinn, Suzanne Lynch, John O’Brennan, Ben Tonra, Bobby McDonagh, Noelle O’Connel, Lucinda Creighton, Eoin O’Dell, Eoin Drea and Brigid Laffan.

These leading business, academic and political figures prove a unique source of reference marking this most important milestone for Ireland and the European Union over five decades.

The forewords are written by Ursula von der Leyen, President European Commission, and Paschal Donohoe, President Eurogroup of Finance Ministers.

Note: This piece was originally published as a cover story in the December 2022 issue of Business & Finance magazine, available to read, with compliments, here.

Fifty years ago, Ireland was an underdeveloped country at the edge of Europe. The economy was heavily dependent on agriculture and one of the main exports was its people. Support for membership of the common market was widespread and the referendum was carried by an overwhelming majority.

Regional economy

The decision to join the then fledgling EEC has been transformative. From the period of independence up to the 1970s, Ireland was effectively a regional economy of the United Kingdom. Indeed, it would not have been possible to join the common market if the British government had decided against such a move.

From accession through to the late 1980s, the Irish economy remained at the bottom of the EU league because of inappropriate domestic policy.

But the decision in the early 1990s to open the economy to investment coincided with the creation of the single market. An attractive corporate tax rate persuaded US multinationals, in particular, to establish their European bases in Ireland. This country is now a world leading centre in the areas of pharmaceuticals, ICT [information and communications technology], social media, medical devices, and many other sectors. Apple, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Dell, Microsoft, Medtronic, and Pfizer are just some of the global companies that have European headquarters in Ireland.

Relationship with the UK

EU membership has not just been about economic development; it has helped Ireland overcome its reliance on the UK. Irish Taoisigh and ministers sat around the EU table as equals to their British counterparts. Common membership of the EU was crucial to framing the Good Friday Agreement, the historic peace accord that brought an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Indeed, John Hume, who was a member of the European Parliament for twenty-five years, got much of his inspiration for the peace process from European integration in the post-war period.

The Irish economy hit the buffers in 2008, amid a global financial crisis. A massive credit bubble formed in the decade leading up to the crash through a combination of domestic policy failures and flaws in the institutional architecture of the European Monetary Union. There have been a number of far-reaching reforms since then at a European and national level, including EU banking union and much more comprehensive fiscal rules. The EU also crossed a previous red line during the Covid-19 pandemic through the issuance of common debt to fund the recovery throughout the bloc.

But the money borrowed by the commission will have to be paid back eventually and that means the EU will have to start looking at extra revenue raising measures. Environmental taxes are an obvious option, but corporate taxes will also come under consideration.

OECD-backed initiative

The Irish Government has signed up to an OECD-backed global initiative that proposes a minimum corporate tax rate of 15% for companies with annual revenues above $750m. This initiative has hit a number of roadblocks and its introduction has been delayed until 2024. Indeed, there is a growing likelihood that the proposed 15% rate could be derailed by political opposition in the EU and the US.

If that happens then the European Commission is likely to renew efforts to harmonise the corporate tax regime and set a minimum rate among member states. This would pit Ireland against the Commission and a majority of member states, including the powerful Franco-German axis.

The EU is evolving and that presents opportunities as well as challenges for Ireland. Possibly the biggest challenge stems from the decision by the British people to leave the EU following a referendum in June 2016. The consequences for Ireland and the peace process were never discussed during the referendum campaign.

Brexit

The European Commission and remaining twenty-six member states provided steadfast support for Ireland’s position that there can be no return to a hard border during Brexit negotiations. After difficult and protracted talks London and Brussels reached a compromise through the Northern Ireland Protocol.

The British government has introduced legislation that would unilaterally dismantle key parts of the deal struck between the EU and the UK. At this juncture, it is unclear whether the UK government will follow through with the legislation and risk a trade war with the EU.

Whatever the outcome, it is clear that Anglo-Irish relations are at their lowest ebb since the early 1980s. What is now needed is a new institutional framework to re-establish ties between the two countries.

Security and defence will also present huge challenges for Ireland over the coming years. The Russian invasion of Ukraine underlines the changing geo-political landscape and the increasing risks to all EU member states. Ireland is the headquarters of a number of US multinationals. There are vitally important undersea cables connecting Ireland to the US and the EU. These cables are an obvious target for Russian sabotage efforts.

As it stands, Ireland lacks the defence capabilities to patrol its own waters yet the majority of the Irish public are implacably opposed to any moves towards pooling EU defence and security resources. This position is not tenable in the long term and it will pose significant challenges for future governments.

Alliances

There are other strategic challenges facing Ireland in terms of EU membership. Ireland shared a broadly similar approach to EU membership as the UK. Now Britain has departed Ireland has lost an important bulwark against some of the federalist tendencies of the core member states.

The Government needs to forge stronger alliances with member states that share a similar outlook to Ireland.

Ireland has always punched well above its weight in terms of being represented at the higher levels of the EU. Catherine Day and David O’Sullivan have both held the office of Secretary General of the European Commission. This conveyor belt has stopped in recent years. It must be a priority for the Government to get it up and running again.

Most importantly of all however, every effort must be made to ensure that public opinion remains favourably disposed to the EU. Membership of the single market is key to Ireland’s future prosperity.

Ireland-EU at 50 is available for purchase.

Startups: Becoming one in a million

“Difference is an accident of birth, plain and simple” – In conversation with John Hume Jnr.