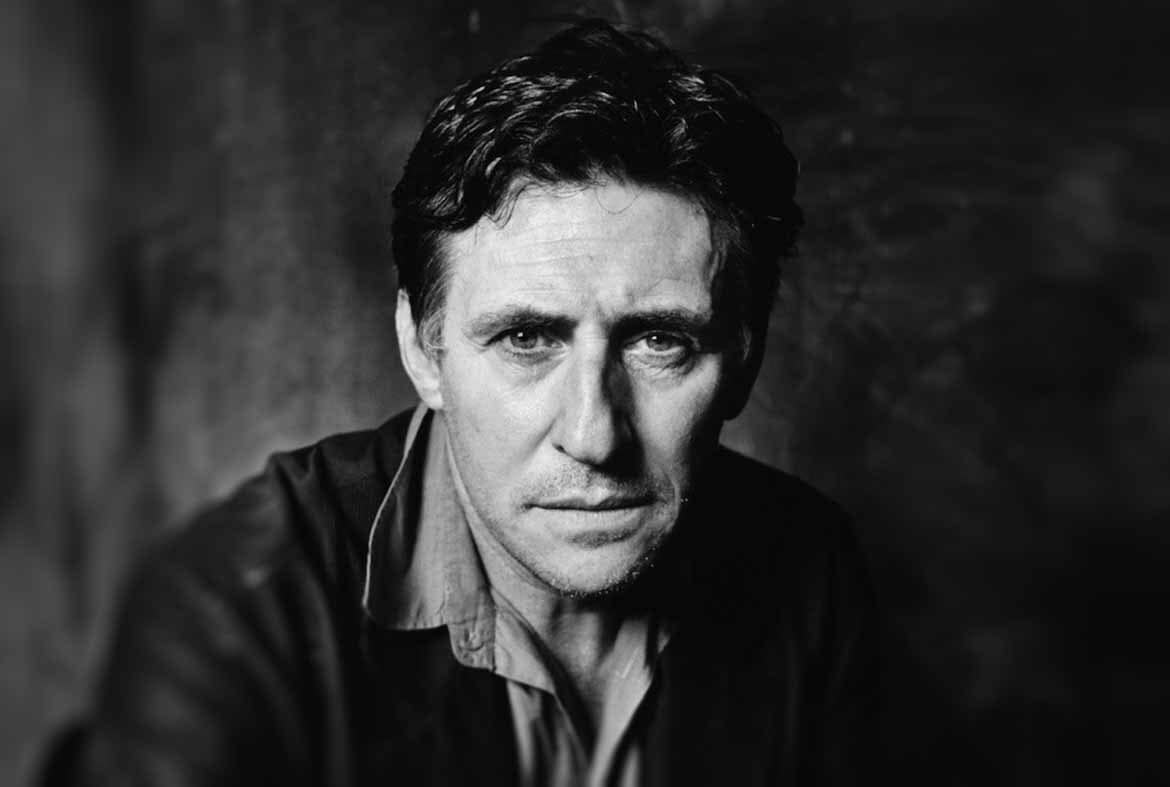

Gabriel Byrne has starred in more than 100 feature films, and on Broadway he has received 3 Tony Award nominations. A prolific career with a considerable contribution to Irish cultural and public life, he was the perfect choice for 2023 TK Whitaker accolade at the Business & Finance Awards, hosted in December, 2023.

Here he discusses his career, the importance of the arts, Irish identity and culture, and what it means to be a leader with David Monaghan, Deputy Editor of Business & Finance.

Leadership

We are sitting in a bar in the Shelbourne and Gabriel Byrne is happy to be in Dublin, the city in which he came of age against a backdrop of religious and societal oppression. It is December 7th, 2023, and in amongst the din of diners and drinkers, we discuss his illustrious career.

Byrne has starred in more than 100 feature films including Excalibur, Miller’s Crossing, Into the West, Little Women, The Usual Suspects, The Man in the Iron Mask, and many more. For his work on Broadway, he has received 3 Tony Award nominations and has twice won the Outer Critics Circle Award for his performances in the works of Eugene O’Neill.

On the small screen, Gabriel Byrne won a Golden Globe Award in 2008 for his lead role in HBO’s In Treatment, while recent TV appearances include acclaimed roles in Vikings and the 2019 adaptation of HG Wells’ The War of The Worlds. He has been nominated for 3 Emmy awards.

When we speak, Byrne is set to receive the 2023 TK Whitaker Award for Outstanding Contribution to Public Life at the Business & Finance Awards.

Does Byrne view himself as a leader? “I don’t … Except maybe leading by example, which to me is the best form of leadership.”

He continues: “There are people who are naturally charismatic leaders, but what they do is they bring a coherent vision together, and they’re able to articulate the needs and the wants and the aspirations of an audience. But I think that leading by example … If you are a kind person, you don’t have to stand up and say ‘I’m a kind person.’ Kindness is something that is seen and … makes an impact on people.”

“If you are a kind person, you don’t have to stand up and say ‘I’m a kind person.’ Kindness is something that is seen and … makes an impact on people.”

“So, if I’m passionate about the arts and what I think the arts should be … I think people, it’s not that they learn from it or anything, but they say, ‘hm, maybe he has a point.’”

Byrne also notes that ‘practical things,’ like his work for the Irish Arts Centre in New York, “that is the manifestation of this passion for the arts.”

Cultural Ambassador

Byrne is proud to have been a co-founder of The New Irish Arts Centre in New York, a project that took 20 years and 80 million dollars to complete. Since its inception it has now become one of the city’s most prestigious cultural venues.

How did it come about? “I had given this speech at a dinner about the Irish-American identity, artistically speaking,” says Byrne, “and realised that we had a tremendously powerful artistic identity on this side of the world, but nothing on that side of the world. So the idea was to bring both of those cultures together.”

The building that represented the original Irish Arts Centre was “a run down, rat-infested place” on 51st Street, says Byrne.

“And we thought we have to have something that reflects who we feel we are, and the contribution that Irish arts has made to the world, and to America as well especially.”

And so, a group of people came together after that dinner to build a new identity of Ireland in America. They raised $65 million, says Byrne.

“And the building is now probably one of the top venues for the arts in New York. And so consequently, in America as well. So, to me, that’s a tremendous achievement.”

Ireland and the Arts

A very consistent Irish export is culture: poetry, drama, writing, acting, music.

Says Byrne: “We do have great poets, great writers, great dramatists, and I think that has something to do with history, where the Irish tradition and the Irish culture had to go underground.

“And it had to become, by the fact that it was repressed, an oral tradition. So people sat around fires and it was the only time, the only way they could actually express themselves artistically – hedge schools, firesides.”

Another factor in the development of Irish writers in English was the “the clash between the English language and the Irish language,” says Byrne.

“If you speak a language, you think philosophically in a particular way, and Irish language, the sound of it, not so much the content of it, but the sound of it and the beauty of it clashed with the English language, and out of that came a particular kind of English, exemplified, I suppose, by people like Oscar Wilde, Shaw and Yeats and so forth.

“And it had to become, by the fact that it was repressed, an oral tradition. So people sat around fires and it was the only time, the only way they could actually express themselves artistically – hedge schools, firesides.”

“But they would not have become the artists they did if it hadn’t been a hidden tradition that they inherited.”

Byrne reasons that if it hadn’t been for our shared history with the Sceptred Isle, and the clash of our respective cultures, we would have developed a lot differently artistically.

“And it’s interesting to look at the personalities of those men, like, for example, Yeats came out with the Celtic tradition and redefined what it meant to be Irish. Oscar Wilde got English audiences to laugh at themselves, a thing that they didn’t even know they were doing. Joyce redefined the novel, Beckett redefined the drama.

“And although they all had conflicted relationships with the country, it was that conflict that allowed, I think, it’s a theory, but that allowed them to produce something. Also, the kind of people that we are. We tend to be passionate and voluble and like somebody said, we’ll never use one word when a hundred will do. And again, Oscar Wilde said the Irish were the greatest talkers since the Greeks.”

Beckett

Byrne recently played Samuel Beckett in the biographical film Dance First, which also featured Aidan Gillen as James Joyce.

Byrne was familiar with Beckett’s work, having read it in university. However, at the time, he “didn’t respond to it at all.”

He continues: “I just thought it was boring and cerebral. When I went to the theatre, I wanted to be emotionally connected to the material, and I just didn’t find it with [Beckett], nor did I find it with Pinter or Tom Stoppard either. But anyway, I came to realise that of course, Beckett was brilliant.”

Brilliant how? “He was more of a philosopher who was a dramatist, and he wasn’t interested in getting your emotional reaction to it, and he wanted you to see with absolute ruthless honesty what it means to be a human being, what it means to live this life, to begin it, to live it, and to the end of it.

“[I realised] ‘Oh, that’s what he’s about. Okay. He’s writing about the human condition here, so it’s not going to be the same as going to see Juno and the Paycock or whatever.’”

Religion, Influences, and Upbringing

Byrne’s return home is a joyous one. However, “the last couple weeks especially have been momentous,” he notes.

At the time of interview, it had been two weeks exactly since far-right agitators, exploiting a knife attack on a woman and three young school children that had occurred earlier in the day, stirred racist sentiment, the violence of their rhetoric spilling out from messaging apps like Telegram, WhatsApp and Facebook and onto the streets of the Irish capital.

Approximately 500 people participated in the riot, damaging property, including four Dublin buses and a Luas tram. Then Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, stated that repair of damages may cost up to ‘tens of millions.’

Says Byrne: “You know, when you turn on the American television news and you see what you think might be some, you know, some trouble spot in the world, and it’s Dublin […] You think, ‘oh, my God, this is so shocking.’ And yet when you start to really think about it, is it so shocking?”

Byrne is referring to the social and economic forces that produced this night. “It became a tinder point for a lot of things, a lot of anger that’s there underneath the surface and a lot, of course, anti-immigration feeling.”

“And the way [Catholic leaders] dealt with people who were different in any shape or form, you could equate that with the extreme far-right here, except that they were institutionalised and they were protected by the law.”

Byrne says the far-right is not a new concern. “I think the far-right was never gone. It’s always there. And it needs somebody to strike them out […] And I think they say that one of the real threats in America at the moment, and there are many, is militant Christianity.”

Byrne likens the Christian extremism of the United States to the stringent and strict Catholicism of his youth: “And there was … militant Catholicism in this country, where people were forced to live almost in a repressive dictatorship.

“And the way [Catholic leaders] dealt with people who were different in any shape or form, you could equate that with the extreme far-right here, except that they were institutionalised and they were protected by the law … It’s not something that flared up the other night. It’s always dormant.”

Byrne has been critical of the Catholic Church for much of his career, for the oppressive nature of its control on Ireland. The impact of his Catholic upbringing is explored in affecting detail in his 2020 memoir Walking with Ghosts, which was adapted for the stage as a one-man show at the Gaiety Theatre in February 2022.

The process of writing the book was an introspective one for the Golden Globe winner: “Part of the journey that we all take in life is we get to certain places and then look back and we say ‘who was I then, who am I now, who am I going to be?’

“So, you look at these things and you see yourself not as this kind of isolated individual, but you see all the things that go into making you, like being raised Catholic, which was a huge, huge influence on my life. I’ve been trying to get rid of it for a long time and can’t because, I was just thinking to myself the other day, how much guilt was inculcated into me as a child, and how difficult that is to get rid of as you get old.”

The Shy Man’s Revenge

Byrne informs me that he is shy. This is in spite of a prolific acting career. “It’s a contradiction I could never really make sense of,” he says.

“And they say that acting is the shy man’s revenge, and I think there’s a certain amount of truth in that. Maybe it’s some kind of revenge for feeling that I had to sit at the back of the class, even though it’s hard to rid yourself of the personality of the kid at the back of the class.

“You never quite get out from behind it because that’s the way I saw the world … My education made me feel like that, living in Ireland made me feel like that. So I felt like an outsider at school, and I felt like an outsider outside of school, you know, and when I went to America I felt like an outsider there, and coming back here an outsider.

“So maybe acting or writing is a way of trying to make sense of it. Joyce’s relationship with Ireland is built to a great extent on a kind of anger, and I understand. Sean O’Casey is the same. Shaw less so.

“But I think trying to make sense of who you are both in terms of your own personal identity and who you are as a citizen of this country is a lifelong thing, because I still don’t know actually who I am.”

See Gabriel Byrne’s acceptance speech below

Read more:

Highlights of the Business & Finance Awards 2023, in association with KPMG Ireland

“Difference is an accident of birth, plain and simple” – In conversation with John Hume Jnr.