More cohesive EU policies on banking, benefits and borders will build a sustainable union, suggests Sergei Guriev, chief economist, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

The past year has been full of watershed developments. Aside from Donald Trump’s victory in the United States’ presidential election, some of the European Union’s weaknesses were fully revealed, with the United Kingdom’s vote to leave casting the bloc in a particularly harsh light.

But Brexit does not have to spell the Union’s demise. Instead, it can serve as a wake-up call, spurring action to address the EU’s problems.

Some European leaders are attempting to heed that call by urging EU member states to ‘complete the Union’. Without the UK, they argue, it will be easier to advance integration, as the remaining members are somewhat less heterogeneous, and therefore more likely to agree on steps that Britain might have opposed.

One such step – and a constant focus of attention since the euro crisis began – is a banking union. While substantial progress has already been made on this front, European banking integration is far from complete. Unfinished business includes a deposit-insurance scheme, as well as the creation of a senior tranche of safe sovereign assets, or eurozone-wide risk-free securities.

UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE

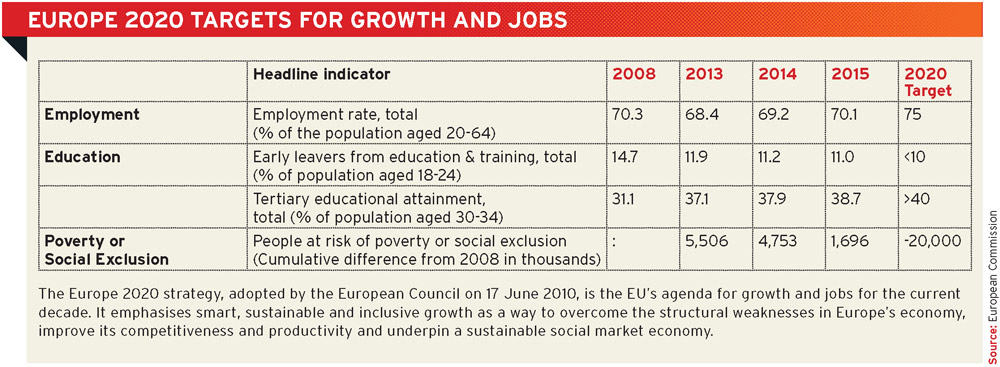

Another potential step, motivated by the profound asymmetry of eurozone countries’ economic performance during the crisis, would be a joint unemployment-insurance scheme, whereby cyclical unemployment benefits would be financed from the EU budget.

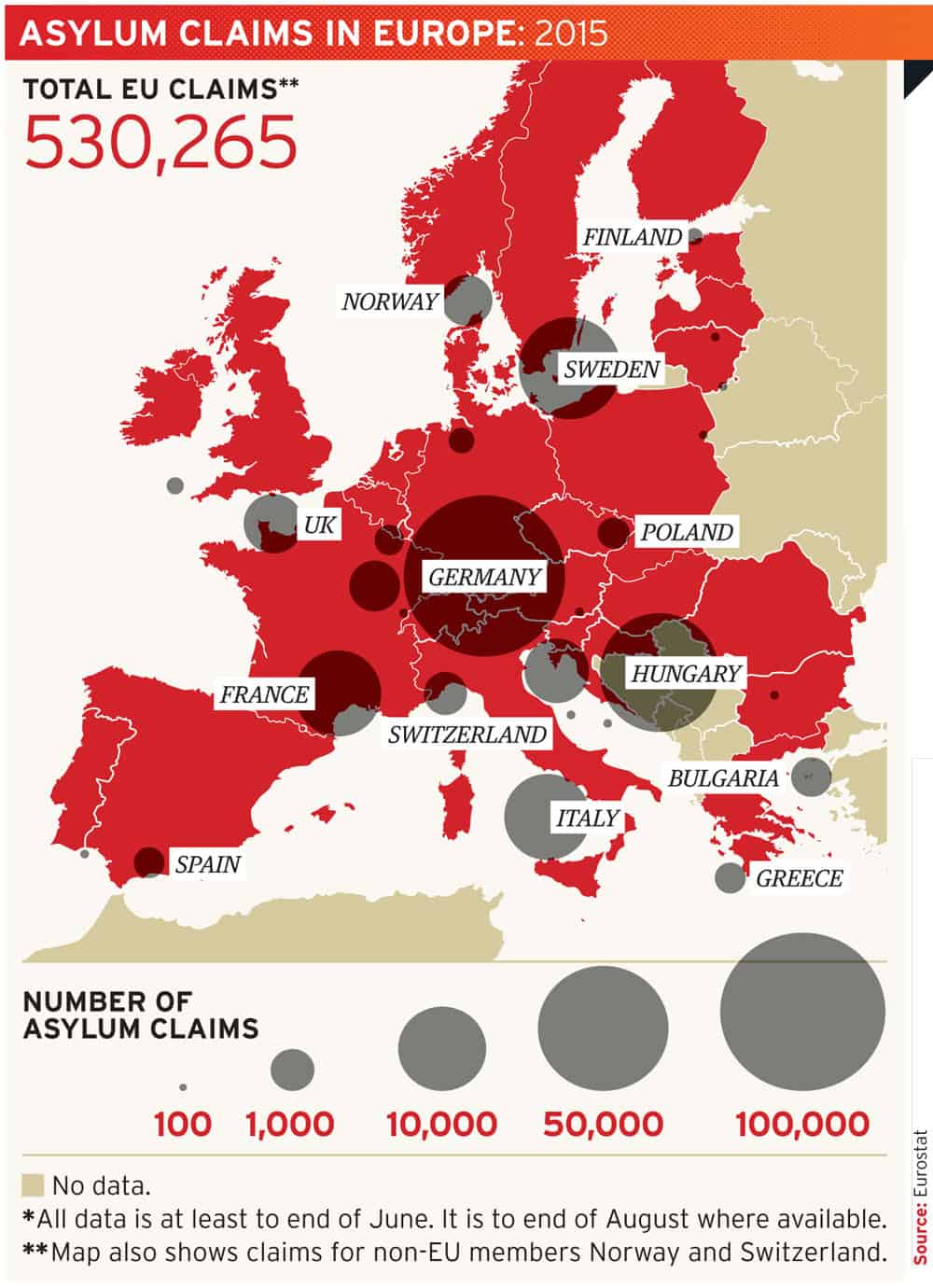

Finally, the refugee crisis has led to a discussion of a joint scheme for enforcing the EU’s external borders, allocating asylum-seekers among its member countries, and financing their integration.

All of these – and many other – ideas have been discussed at length, and have even been elaborated to the point that actionable agendas have emerged. Yet little progress has been made. The UK, it turns out, is far from the only source of political resistance to deeper integration.

Of course, who opposes integration depends on the specific proposals, all of which are likely to benefit some EU members more than others. In some cases a proposal might result in greater long-term gains for all, but carry significant up-front costs for particular countries.

At a time when some major EU member countries are set to hold national elections, and when anti-establishment politicians are deposing moderate parties, many national leaders are unwilling to risk their political capital to push through such reforms.

PACKAGING PROPOSALS

But what if the reforms were made more appealing? Breaking down political resistance may be as simple as packaging proposals together. The proposals with greater benefits for some could be combined with and counterbalanced by those with greater benefits for others, and the short-term costs of one policy could be offset by the shorter-term gains of another.

Consider efforts to address the refugee crisis. Once it became clear that some countries, particularly in central Europe, were unwilling to accept EU-imposed quotas for resettlement, it was proposed that asylum-seekers be permitted to choose where they want to settle. The EU budget would cover the costs, potentially using newly issued safe bonds.

If the EU is to remain a beacon of openness and liberal democracy, it must forge ahead with integration

But this idea could also run up against resistance, not least because the countries that would attract the most refugees are those that already have stronger economies, and therefore need EU funding the least.

The solution would be to introduce another measure, producing transfers in the opposite direction, in tandem with the refugee policy.

The best candidate for this role may well be the joint unemployment-insurance scheme. Countries that are undesirable to refugees, owing to high cyclical unemployment, would benefit disproportionately from such a policy, especially in the short term.

The expectation that those transfers would eventually be offset by refugee-resettlement funds may be just what is needed to get low-unemployment countries on board.

To be sure, on the refugee issue, in particular, there may be added complications. Social resistance to immigration in a country like Germany, fuelled by terrorist attacks and populist political rhetoric, could undermine the appeal of such a programme. But in that case the specific policy package could be adjusted.

Packaging reforms to make them more palatable may sound like Business 101. But this is not just about quotidian deal-making.

Rather, it is about completing – and thus protecting – the EU, by building a more sustainable set of institutions. If the EU is to remain a beacon of openness and liberal democracy, it must forge ahead with integration. If it is to make headway, its leaders will have to ensure that all members benefit equally along the way.