“My instinct is with the landless, and with the breadless man against the master of millions” – Pádraig Pearse

Numerous absorbing and dynamic interviews and features have graced the pages of Business & Finance during its history. Through the Decades looks back at a selection of articles, showing how the Irish economy has evolved.

The aims of the leaders of the rising of Easter 1916, were almost entirely nationalistic. Basically they wanted to free Ireland from foreign domination. Given this freedom, they assumed that all the ills from which they were suffering – political, social religious and economic – would automatically disappear.

There was only undoubtedly a great deal of social and economic unrest, however, as evidenced by the general strike and the lockout of 1913.

Some of the leaders of the freedom movement had devoted some thought to the desired economic system after achieving freedom. Of the most important groups in the struggle, the Sinn Feiners were capitalists in their economic policy, and indifferent or hostile to the workers.

Arthur Griffith tended to influence the economic ideas of the Sinn Feiners. He advocated that pressure should be exerted on the banks of the stock exchange to make them more sympathetic to Irish commercial undertakings. Irish waterways should be developed and an Irish mercantile marine founded. He laid special stress on the need to develop native industry and manufactures, and for this purpose he favoured a policy of protection.

Éamon de Valera pictured during the 1930s

A CHAMPION OF THE WORKERS

Connolly was a socialist and the champion of the workers. He declared in the first addition of the ‘Workers Republic’ (1898) that, “We are Republicans because we are socialists.” His economic philosophy is summed up by an article in the same journal for January 15th 1916, which merits quotation at length: “All the material – the railways, the canals and their equipment – will at once become the national property of the Irish State.

It is not possible … to attempt to evaluate the Irish economy today in terms of whether or not it has lived up to these ambitions of two of its greatest architects

All the land stolen from the Irish people in the past, and not since restored in some manner to the actual tillers of the soil, ought at once to be confiscated and made the property of the Irish State … All factories and workshops owned by people who do not yield allegiance to the Irish government immediately upon its proclamation should at once be confiscated, and their productive powers applied to the service of the community loyal to Ireland, and to the army in its service.”

In his later writings upon economic subjects, Pearse seems to have come under the influence of Connolly. He declares on the one hand that: “My instinct is with the landless, and with the breadless man against the master of millions.” For both Pearse and Connolly, ownership of Ireland by the Irish was the prerequisite for prosperity, freedom from hunger and exploitation, and thus for happiness. Discussing hunger, he bitterly wrote, “The very poorest can enjoy it, and it is one of the few luxuries that the rich will not grudge them.”

DIMINISH EXTRAVAGANT EXPENDITURE

In the ‘Hermitage’ he states: “A free Ireland would drain the bogs, would harness the rivers, would plant the wastes, would nationalise the railways and waterways, would improve agriculture, would protect fisheries, would foster industries, would promote commerce, would diminish extravagant expenditure, would beautify the cities, would educate the workers (and also the non-workers who stand in direr need of it) would, in short, govern herself as no external power – nay, not even government of angels and archangels – could govern her.

He maintained that his insistence upon sovereign control of the nation over all the property within the nation was not to disallow the right to private property. But he was willing to allow increasing degrees of socialism if the nation desired it.

Some of the leaders of the freedom movement had devoted some thought to the desired economic system after achieving freedom

It is not possible, nor is it really fair, to attempt to evaluate the Irish economy today in terms of whether or not it has lived up to these ambitions of two of its greatest architects. Not only were they executed before they could put there economic ideas into practice, but even the Irish government of today is not in a position to influence every one of the 32 counties of Ireland.

However, the Ireland of today has as much state intervention in her economy as any country outside the Iron Curtain. Until recently, to call this development ‘socialism’ would have incurred the wrath of the Church. Connolly was unpopular with the ecclesiastical authorities for his espousal of socialism. Since the time of Pope John the 23rd, however, socialism has become respectable and more acceptable.

The first Dail of 1918, in its own way did a lot for agriculture and finance, and actually issued Republican Bonds to the public both at home and abroad.

Until 1921, when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed giving a large degree of freedom to the 26 counties, no economic progress by a free Ireland was possible. In 1921 the Irish Free State was still largely an agricultural country. Most of the industrialisation which had come to Ireland had been concentrated in the north-eastern counties, over which the Dublin government had no jurisdiction. The majority of the population were living on the land. Apart from a few large industrial concerns, most of industry was engaged in small-scale production.

There is very little statistical material available for the early years of the Free State. Agricultural statistics were collected quite regularly and there was a Census of Population in both 1911 and 1926. From both these sources it is possible to build up a picture of part of the economic structures of the 26 counties.

In 1916, just under 1,000,000 acres were under corn crops, about 65,000 acres being under wheat. Nearly 10.5 million acres were in grass. There were over four million cattle, nearly 3.5 million sheep and over one million pigs.

The 1926 Census of Population reveals that there were 2,971,992 persons at work, 53% were engaged in agriculture, while 13% were working in industry.

The first statistics relating to industrial production in the area of the State were collected in 1926. In 1926, the gross output of the transportable goods industries was £49 million, the net output was £16 million, and the number employed was 57,770. Brewing was by far the most important industry. National income in 1926 has been estimated at £164.5m.

INDUSTRY IN A VERY POOR POSITION

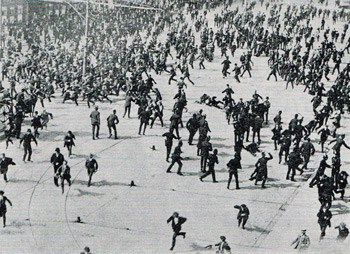

The 1913 General Strike

Irish industry was in a very poor position with regard to potential development. The country lacked indigenous raw materials, a reserve of skilled labour, machinery for mobilising available savings for capital investment, efficient management and marketing organisations, and an ‘industrial tradition’.

Just as the political history of Ireland has been rather chequered since 1921, so also has the economic history of the country. Economic growth was at a very slow pace until the late 1950s. The whole period from 1921 to 1932, the foundations of the Irish economy were laid and slow and rather spasmodic progress was made.

Just as the political history of Ireland has been rather chequered since 1921, so also has the economic history of the country

From 1932 until 1938, the Irish economy was suffering from the effects of the ‘Economic War’ with the UK. 1938 to 1945 may conveniently be termed the war years, during which Ireland certainly received many benefits. The post-war period, from 1945-1958 was a mixture of years of prosperity with years of crisis while the final period, from 1958 to the present day, has seen the economy growing rapidly, albeit still not safe from economic crisis.

This is an extract from a larger feature Patrick Lyons wrote in Business & Finance’s April 1966 which marked 50 years since the 1916 Easter Rising.