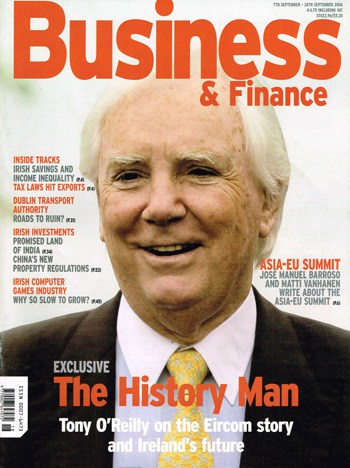

Numerous absorbing and dynamic interviews and features have graced the pages of Business & Finance during its history. Through the Decades looks back at a selection of these articles.

Anthony O’Reilly, 2006

Constantin Gurdgiev speaks to Anthony O’Reilly about eircom’s turnaround and the rollout of broadband.

Following the sale of eircom, giving investors a 62% return, Anthony O’Reilly stepped down as chairman in 2006.

Constantin Gurdgiev (CG): Sir Anthony, your legacy here in Ireland will inevitably be associated with your chairmanship of eircom. Following the sale of eircom to Babcock and Brown (B&B), and the delisting of eircom, the overall record of the company in opening markets and unrolling broadband came under renewed scrutiny. In your view, was eircom’s privatisation a long-term success story for shareholders, the Exchequer and customers?

Sir Anthony O’Reilly (TO’R): From the point of view of the shareholders and consumers, the privatisation of eircom, in the end, was a success. In Ireland, telephone bills today are substantially below the levels seen prior to privatisation. We have access to quality service on a far greater scale than before. Competition has been good for the industry. I think it is indisputable and from that point of view you can say that the privatisation of eircom has been a success.

Look at any other service, or range of goods available in Ireland. Since the 1990s, all of these increased hugely in cost. Probably, the only two cases of clear reductions in the cost of services along with improvement of quality are in telecommunications and airlines. These are the only two sectors and the credit there goes to Ryanair and eircom.

CG: In fact, broadband appears to be the magic word for anyone looking at criticising eircom during the whole post-privatisation period. It is the area where eircom is being increasingly pressured by the government and ComReg.

TO’R: I can ask you in return – in your own experience is there a single country where the telecom company is popular? Were AT&T or BT or Ma Bell ever popular? Whenever anyone wants to bitch about something, it’s the telephone company that first comes to mind. Telecom Éireann – with all its posts and wires – was unpopular. When your line went down or you couldn’t get a connection you blamed the company. Telecoms were always beat-me-up boys everywhere, not just in Ireland.

CG: On the other hand, eircom was oversold by the government, wasn’t it?

TO’R: The primary beneficiary from the privatisation of eircom was in fact the State – it got £8bn, which, with some serendipity, the government put into a pension fund. At least a large share of it. So not all of it was lost to the Irish people, although admittedly a very specific group of Irish people.

But given the whole environment of, first, the dotcom revolution, and then its collapse – eircom was bound to run into disfavour. I mean, here is the most over-marketed stock in the history of this country, and given the fact that the public do not particularly like telephone companies in any event, and then the stock falls. What do you expect?

But given the whole environment of, first, the dotcom revolution, and then its collapse – eircom was bound to run into disfavour. I mean, here is the most over-marketed stock in the history of this country, and given the fact that the public do not particularly like telephone companies in any event, and then the stock falls. What do you expect?

Very few people can define what broadband really is and subsequently what eircom is supposed to deliver

Do you remember that famous AGM when some 2,000 people showed up at the RDS? It went on for eight hours. From that unpromising start, eircom decided to sell its mobile unit, which it did rather well.

When you compare with the condition they were in and if you look at Vodafone today – it was a terrific deal. The board of Ray MacSharry rescued what was a very unpromising situation: an unpopular and over-marketed telephone company. They got 220p per share at the time, some £4bn. If you actually had shares of Vodafone on that day, you would have got something around the same valuation.

Today, with all that Vodafone achieved around the world, the enormous deal with Mannesmann, expansion in Japan, the globalisation of Vodafone, the shares are worth only 113p. So, eircom was left with the fixed-line business and that business is declining everywhere around the world. The real question then is at what rate is it going down? In point of fact, in Ireland the number of new connections is not declining.

The mobile market went up dramatically since the late 1990s, but Irish fixed-line business remains pretty much the same today because our population has gone up dramatically. This performance stands in contrast with, say, France or Germany where the fixed-line business has fallen some 5% per year over the last six years.

BREAKING NEWS

CG: Following the sale of the mobile division, eircom had an auction between E-Island and Valentia. It was one of the most fiercely contested auctions in the history of this country.

TO’R: Yes, starting off at 110 – E-Island’s original offer. The price finally got to 137.5 but was defeated. In fact, Business & Finance broke the story. Certainly the market thought that we in Valentia paid too much for the company.

CG: After the auction, HSBC stated: “It is hard to imagine that Valentia is not overpaying for eircom. It remains to be seen if O’Reilly’s bid represents a misplaced nationalism or the over-heated bidding process.” So, in August 2001, the public image of the company remained less than favourable. Do you think that there is a part of our psyche that still views eircom as some sort of a State or public asset, rather than just a company?

CG: After the auction, HSBC stated: “It is hard to imagine that Valentia is not overpaying for eircom. It remains to be seen if O’Reilly’s bid represents a misplaced nationalism or the over-heated bidding process.” So, in August 2001, the public image of the company remained less than favourable. Do you think that there is a part of our psyche that still views eircom as some sort of a State or public asset, rather than just a company?

TO’R: Well, now, turning to that misplaced nationalism … I think this is a good quote to start the whole story of the eircom privatisation. You are right about the public perception of eircom. In fact, in the public view, eircom has ‘a responsibility to the common people of Ireland to deliver to them that which is most desired’. And today this, of course, is broadband – instant broadband. With on-demand video: you name it, and it is their responsibility to deliver it.

There’s an attitude in Ireland, which I would describe as an entitlement attitude. Remember – we were quite a socialised society in the past. We felt that the government owed us telephone services, proper water, roads. When we talked about economic issues we talked about the government and it was an entirely different Ireland from what we have today. That is changing and today we have a society where everyone fundamentally now understands that goods and services have to be paid for by the consumer.

BROADBAND VS NARROWBAND

CG: And yet this spirit of self-reliance does not exactly hold when it comes to things like broadband. In broadband, the government tries to fundamentally alter the way the private sector operates by setting centrally planned targets for coverage and quality. These are based on what one may call artificial spatial development objectives, whereby the State sees certain services, such as telecommunications and broadband, as a necessity to be delivered to every home. This now forms an effective State-set benchmark for eircom. But what does this mean for the future of the company?

TO’R: Broadband is the issue which is not fully understood. First of all very few people can define what broadband really is and subsequently what eircom is supposed to deliver. I can go to the Dáil and ask all of the TDs what they mean by the term broadband and what is the cost that you would expect to pay for it. There will be no single answer. There are huge questions that remain unanswered and we had no proper discussion as to what it is that the State expects us to deliver and at what speed and at what cost.

There is this wonderful myth that goes something like this: ‘the people of Ireland will not achieve the optimal rates of economic growth if they do not have broadband.’ Now, the people of Northern Ireland do have broadband, with almost 100% coverage, and they have almost no capital investment going into their economy, while we have one of the highest rates of capital inflows in the world. So allegedly, having limited broadband we still have dramatic capital investment but are now being told that if we don’t achieve 100% coverage of broadband services we will not achieve optimal economic growth. There has to be something wrong with this proposition.

In reality, what happened in Ireland is that we put in place a flat-rate narrowband dial-up service that supplies access to the internet at the cheapest price possible – €9.99 per month, less than half, I repeat, less than half of the average European price.

In reality, what happened in Ireland is that we put in place a flat-rate narrowband dial-up service that supplies access to the internet at the cheapest price possible – €9.99 per month, less than half, I repeat, less than half of the average European price.

The people of Ireland will not achieve the optimal rates of economic growth if they do not have broadband

This allows you access to your emails and allows you buy airline tickets, etc. Tens of thousands of households in Ireland are happy to subscribe to it. It was a brilliant move by Dermot Ahern [minister for communications, marine and natural resources at the time]. It was based on fixed-line connections and eircom was required to provide this.

This made broadband marginally less attractive to many households that required access to the internet for the services I have described above. So giving a consumer an elective choice – broadband or narrowband – many consumers opted for the cheapest service. We now have 400,000 customers using narrowband access for as little as a few euro per month. Compare this with broadband that will cost you €30 per month.

eircom has roughly 75% of this market. But we also have an excellent broadband product at excellent speeds and it appears to be growing at a rate of 100,000 new users every six to eight months.

REACHING TARGETS

CG: But there is more to the story of broadband versus narrowband in Ireland. In fact, the cable delivery is a good example of how we can get policy wrong despite setting broadband targets.

TO’R: Going back in history, Independent News and Media was a part-owner of the American cable provider Chorus. In the US, cable provides 40% of broadband. In Ireland until recently, cable supplied next to zero, primarily because the regulator decided to make no price increases available to Chorus or NTL for a period of four years for the basic TV service. As a result, we got out of the market for broadband by cable.

NTL will probably never be a major broadband provider in this country and the regulator, in this case, killed off a potential source of broadband competition.

Of course, the advantage of cable delivery is that it can supply all three services simultaneously – telephony, broadband and TV. With eircom the story is similar – eircom went for the very sophisticated broadband solutions around the year 2000 and what they needed to justify that was a broadcasting licence to allow delivery of a triple play of telephony, broadband and TV at the same time.

The government did not make a broadcasting licence available – so the government effectively said no to competition with cable providers. This meant that the very sophisticated equipment in which eircom invested was left idle. So, technology is there, but it is not being used.

The incredible situation is that the original eircom tried to get into the game of delivering comprehensive broadband and then a combination of the flat-rate narrowband services and lack of competition in the cable business meant that the new eircom had to reduce its ambitions. Now this became an issue even though today we have better coverage of broadband than you’ll find in the US, equal to the European average and at a growth rate higher than the European average. With this momentum, the reality is that broadband coverage will not be an issue in two to three years’ time.

CONSUMER CHOICE OR SACRED COWS?

CG: You’ve touched upon a couple of interesting issues rarely discussed in the media. First is the role of consumer choice in setting demand for services such as broadband. The second is whether we really need 100% broadband coverage in this country. Why are our policymakers appearing to be unwilling to simply recognise the reality of the markets.

We have competition, we have technological solutions that are not dependent on eircom, so if there is real demand for broadband, someone surely will come in and offer the supply of this service? Does this point to our policymakers continuing to view some projects as some sort of a sacred cow that must be protected at any cost?

TO’R: Absolutely. When it comes to certain projects, broadband being one, “We must have this” seems to be the response from the policy circles. These are the infamous objectives of the State. Go back and look at the original ones: the re-unification of Ireland, restoration of the Irish language and the draining of the Shannon – all three were never achieved. Happily, broadband in all its variety has achieved its objective and, as I have said, will not be an issue in two to three years’ time.

TO’R: Absolutely. When it comes to certain projects, broadband being one, “We must have this” seems to be the response from the policy circles. These are the infamous objectives of the State. Go back and look at the original ones: the re-unification of Ireland, restoration of the Irish language and the draining of the Shannon – all three were never achieved. Happily, broadband in all its variety has achieved its objective and, as I have said, will not be an issue in two to three years’ time.

The reunification of Ireland, restoration of the Irish language and the draining of the Shannon – all three were not achieved

COMPETITIVE MARKET

CG: There is a theory with some practical implications that when a capital-intensive business like a telecom faces potentially heavy regulation, one strategy to protect the company from regulatory overreach is to convert shareholders’ equity into debt liabilities. This allows companies to plead high costs of regulation and effectively reduce regulatory burden. Some analysts suggest that recent takeover activities in the global telecoms business are driven by similar considerations. In the case of eircom, delisting following the B&B purchase was done on a heavily leveraged basis – is this simply coincident with the global trend or is this an opportunity recognised and capitalised on by B&B?

TO’R: I cannot really answer this for B&B, but they certainly have substantial debt on their hands – around $4bn (€3.1bn). On the other hand, they got a very good company to work with. They got an excellent mobile division with Meteor – the Ryanair of the mobile telecommunications. It’s the area where Vodafone and O2 don’t particularly want to go and Meteor will be, in my view, a great success story in the next few years.

Secondly, eircom has now established a critical mass in broadband. Whether we both are right in the sense of being sceptical about the real profitability of the broadband market, eircom remains supremely competitive in it.

SETTING THE SCENE – 2006

Under the presidency of Mary McAleese and leadership of Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, Ireland’s economic prospects remained strong and growth strengthened further during 2006, with consumer spending reaching a peak. Employment had grown significantly, public finances were in excellent shape and inflation remained low. Who knew what was just around the corner?

Other noteworthy events throughout 2006 included the 25th anniversary of the Stardust disaster in which 48 young people died, the official opening of the Dublin Port Tunnel and the announcement that a deal between the GAA, FAI and IRFU had been reached to allow soccer and rugby to be played in Croke Park.

Other noteworthy events throughout 2006 included the 25th anniversary of the Stardust disaster in which 48 young people died, the official opening of the Dublin Port Tunnel and the announcement that a deal between the GAA, FAI and IRFU had been reached to allow soccer and rugby to be played in Croke Park.

In April, up to 120,000 people lined the streets of Dublin to mark the 90th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, and in June the state funeral of the former Taoiseach Charles Haughey took place in Dublin.