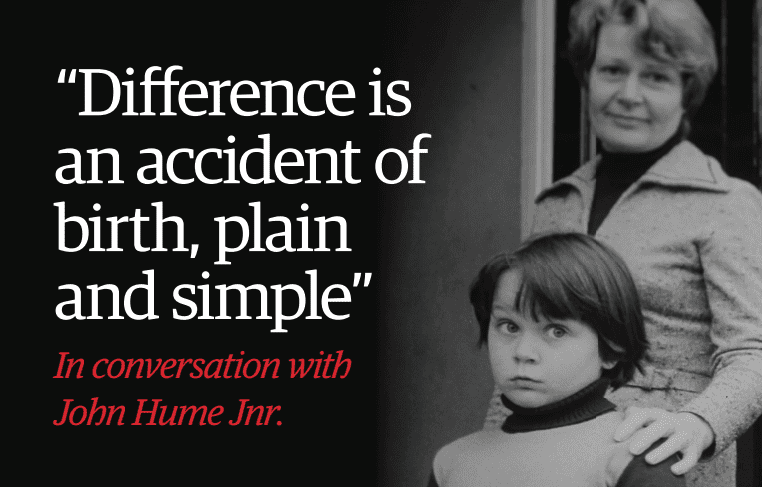

Pictured (L-R): John Hume and his wife Pat arrive at St. Johns Primary School, Derry, to cast their vote in the European Elections

Business & Finance Deputy Editor David Monaghan spoke to John and Pat Hume’s son, John Hume Jnr., ahead of the Business & Finance Awards to discuss his parents’ legacy, their unyielding commitment to peace, and what lessons we can take from their storied lives.

Note: This piece was originally published in Business & Finance magazine, vol. 59, no. 2, available to read, with compliments, here.

John Hume’s influence on politics, both international and domestic, cannot be overstated.

Widely credited as one of the chief architects of the Northern Ireland peace process, Hume was guided by principles of economic and social justice, and a belief that difference is a mere accident of birth.

Born in 1937 to a working-class Catholic family in Derry, Hume was the eldest of seven children. His early years were defined by the day-to-day realities of living in an oppressed community, long stifled by Gerrymandering from a council largely ignorant of the city’s Catholic majority.

As a youth, Hume witnessed his community come under the mercy of loan sharks, who were sought out by the city’s residents to supplement their meagre wages. He helped set up a Credit Union in Derry in 1960 to help combat such exploitative practices, and spent much of his life promoting the merits of the CU movement. He became the youngest ever President of the Irish League of Credit Unions at age 27.

His foray into politics came in 1969 when he was elected a member of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, standing as an Independent Nationalist. He was a founding member of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), and served as its leader from 1979 to 2001.

In his over thirty years of political service, he represented Foyle as a Member of the Legislative Assembly in Stormont and as a Member of Parliament in Westminster. He also represented Northern Ireland as a Member of the European Parliament.

Despite criticism from all sides, he reached across the political divide and engaged in talks with both the British government and Sinn Féin at the height of the conflict in Northern Ireland. This eventually delivered the 1994 IRA ceasefire, which was met with jubilation island-wide.

His work laid the foundations for the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, a pair of agreements that have ensured 24 years of relative peace on the island of Ireland.

He was widely noted for his whole-hearted embrace of non-violent political action. “Politics is the alternative to war,” he said.

Hume married Patricia ‘Pat’ Hone, a primary school teacher, in 1960. One of six children, Pat Hume was born in Derry’s Waterside, and grew up on Cross Street. She was John’s intellectual equal and spent the bulk of her life sharing in his ideas for an Ireland of peace. She became his eyes and ears on the streets of Derry, and was a community leader in her own right.

She eventually left her teaching role to work alongside her husband full-time when he was elected an MEP in 1979, and later set up and ran his campaign office in Derry until he retired from European Parliament in 2005.

In 1998, John Hume received the Nobel Peace Prize alongside then-Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble. He also received the Gandhi Peace Prize and the Martin Luther King Award.

John Hume passed away on 3rd August, 2020, following a long illness. His wife Pat passed away over a year later on 2nd September, 2021.

In December 2021, both John and Pat Hume were announced as the 2021 recipients of the TK Whitaker Award at the annual Business & Finance Awards, in association with KPMG, in recognition of their unyielding contribution to the Northern Ireland peace process.

Established in 2016, the TK Whitaker Award for Outstanding Contribution to Public Life recognises Irish and international social and political leaders who have been exemplary in their contribution to public life.

Business & Finance Deputy Editor David Monaghan spoke to John and Pat Hume’s son, John Hume Jnr., ahead of the awards ceremony to discuss his parent’s legacy, their unyielding commitment to peace, and what lessons we can take from their storied lives.

DM: What are some of your earliest memories?

JH Jnr: We all grew up in Derry, in a place called Westend Park, which is sandwiched between Creggan and the Bogside. It was a great place – great fun, great community. Lovely neighbours, lots of kids in the street. Very normal place with lots of abnormal things going on around us.

DM: What year would this be?

JH Jnr: I was born in ‘68. When things were very, very tough there were five of us in the family. I have two elder sisters, an elder brother and a younger sister. Life was normal, as we thought it was. It’s only now living in Dublin and having kids of my own that I realise it was quite different.

DM: I suppose you were limited by your childhood perspective.

JH Jnr: Exactly. You only have one childhood. But it was a very happy sort of place. Back in the early ‘70s for a brief period, Dad was a Minister in the Stormont government, so he would have been travelling a lot. My earliest memories are of him on television.

DM: Seeing your Dad on television, did that strike you as odd at the time?

JH Jnr: It just becomes one of those things. You become immune to the fact that it is unusual. It becomes an everyday sort of thing. We would have known that Dad had a relatively important role and was a community leader. I don’t think it was, really, until he passed away that we realised how much he meant to a lot of people and the importance of what he did.

DM: At what point did you become conscious of your Dad’s work?

JH Jnr: We always knew what he was doing. In a place like Derry, it was everywhere. I can always remember everyone being very aware of what Dad was doing and what he did for a living and the role he played in the community.

People always talk about Dad as a politician, but I think really what Dad was was a community worker – somebody who was very proud of where he came from, very much part of where he came from, and that was his real goal in life, to achieve change for the better.

I think Brexit would have really upset my father, and he would have fought tooth and nail against Brexit.

DM: What did Derry mean to your Dad?

JH Jnr: He was a very proud Derryman. It was where he came from. He grew up in a place called the Glen, it was what they called a ‘mixed estate’, both Protestant and Catholic. I think that shaped him a lot in terms of his beliefs, ‘we’re all in this together’.

There was Gerrymandering back then, there was a council that was stacked 16-to-8 despite the fact there was a Catholic majority in the city, and that manifested itself in poor housing conditions, in ghetto-like conditions for everyone.

My Dad grew up in a two-bedroom house and there were six children, and that would have been the norm. There was 80% male unemployment. That really affected him. He was a great believer in self help. He was a great believer in the community working to help itself to do what it can.

For housing, he set up the Derry Housing Trust, where houses were built by the community rather than waiting on the council. The Credit Union in Derry was something that was very, very close to his heart.

Dad was a great believer in both social and economic justice, and he really believed that business had a real, powerful role to play in a situation like the North, and he believed that if you can solve people’s economic problems, a lot of the social problems disappear with that, and that would have been part of his mentality throughout his career.

Dad was a great believer in both social and economic justice, and he really believed that business had a real, powerful role to play in a situation like the North.

Before he ever got into politics, Dad built and operated a factory in the Bogside where he smoked salmon from Donegal. He saw all this salmon disappearing into Scotland, to be smoked in Scotland, and the added value of going to Scotland. He decided that he and Michael Canavan, a colleague of his at the time, would build a factory in the middle of the Bogside, and they opened Atlantic Harvest, which is still going today.

That was very much his mentality. I remember he put together a plan for bottling water in 1973. People told him he was mad. He was really into self help and community and the positive power of investment in business. When he got into politics he literally just gave away his shares in Atlantic Harvest because he believed you either had to be a public representative or you had to be a businessman. You could not be both. And that was very much how he did things all his life.

If you look at his career over the years, he was very much into bringing investment into the North, bringing investment into Derry. He set up various organisations over the years to build a bridge between Northern Ireland and the US, and sort of get inward investment. Derry-Boston Ventures was one of those things, which brought in Seagate. Seagate is one of the biggest employers in the North with about two-and-a-half/three-thousand quality jobs in the greater Derry area.

So that was very much his ethos and his philosophy in life, is that business and investment and economic justice is very much part of the problem, and if we can solve the economic problems, a lot of the other ones will fade away in terms of their significance.

Pictured: John & Pat Hume

DM: People talk about your parents in the abstract, but what were they like as people?

JH Jnr: My Mum was, in many ways, fearless. Nothing fazed her at all, and that’s the way I will always remember her. She was also a very practical woman. She was a teacher, and she gave up her teaching career to work with Dad full time, which I think was very difficult for her. It was something she just felt she had to do due to the pressure Dad was under.

As a family, we were shielded from a lot of it. That was very much a decision taken early on. You’ll see very few photographs of the Hume family on election day or anything like that, because we weren’t really part of that, that was very much their thing together. The kids were left out of that. But she was a very pragmatic woman. She knew everybody in Derry. Going shopping with her on a Wednesday night would take three or four hours, because she would stop and she would have time for everybody, and everybody had time for her.

When Dad was off in Washington or Brussels or wherever, she was the antennae, the boots on the ground, because she knew what was going on. She was completely engrained in Derry. She was a great woman, absolutely wonderful.

People always talk about Dad as a politician, but I think really what Dad was was a community worker.

When she passed away, the reaction of people in Derry was really just very touching and we got thousands of messages of support, as we did with Dad, you know? It really showed us how much they were valued and how much they were appreciated across the country.

Dad was, in many ways, a hugely intelligent man, you’d get that from a minute of talking to him. He would often go into himself, would often be deep in thought. You’d be sitting looking at him, but he wasn’t there for hours on end. He enjoyed life, enjoyed singing a song, and enjoyed a late night or two. He was a politician in many ways like that, he sort of enjoyed good company, and he enjoyed a good sing-song and a good night out.

We used to spend a lot of time in Donegal and we could almost see him relaxing as we crossed the border. We’ve had a holiday home in Greencastle in the Inishowen Peninsula, and really, that was a life-saver because that gave them the ability to just relax, take a deep breath and just recharge the batteries, and get away from Derry where quite often things would be getting out of hand.

DM: Did you ever fear for them or worry about them?

JH Jnr: Not really. Certainly, all of us would have feared for Dad’s health, because his life did take a toll on him. The stress, certainly in his later years, did have an impact. And at times, we did worry about his health. In terms of worrying for their safety, not really. You become immune to things like that I suppose. Everyone in the North became immune to the dangers, and if you did worry about things like that, I think you would have gone off your head, I suppose.

Maybe my brothers and sisters would have felt different, and I’m sure my Mum would have felt very different because travelling the dark roads of the North at night back and forth from Belfast, I can imagine. But as children I think we were very much shielded from the worst of it all.

DM: What would you say is your parents’ greatest legacy?

JH Jnr: I think the Good Friday Agreement and how we got there. It didn’t happen overnight, there were various stages to that – the Downing Street Declaration, the Anglo-Irish Agreement, you can date it all back and it took a long, long time unfortunately. But we’ve had more than 25 years of relative peace and prosperity on the island, and whilst the problems haven’t gone away and the naked sectarianism is still there, it’s not like it was before. And if you look at the path that led to the Good Friday Agreement, I think you can see Mum and Dad’s fingerprints all over it. I think that’s really their legacy.

Dad would always say the Credit Union. That was his greatest legacy, and his greatest achievement. How the North has changed, and how this island has changed, is down to him and Mum in many ways. We’re all really, really proud of them.

Pat Hume donates John Hume’s peace awards to the city of Derry. Photo credit: Lorcan Doherty

DM: How would they view the landscape in Northern Ireland today?

JH Jnr: I think Brexit would have really upset my father, and he would have fought tooth and nail against Brexit. Dad was always a committed European, very much so, right from the very beginning. He spent 25 years in Brussels and Strasbourg as an MEP, but he really believed the European Union was one of the greatest achievements in the history of mankind. I think Brexit would have broken his heart in many ways, and it created or recreated a lot of old problems that everyone thought had been put to bed many, many years ago.

I think he’d be looking at the current situation and saying, ‘there is a perfect opportunity here to create an economic powerhouse in Northern Ireland, where you have a unique position where you have access to the European Single Market, yet you also have access to the United Kingdom. It would be the only place in Europe where you’d be able to do that, and there must be advantages to that, there must be an opportunity there to grasp what is good in the protocol.’ Let’s be clear, there are things that need to be worked out, but that’s detail.

DM: If there was one thing that people should take from your father’s career, and indeed, your mother’s career, what would that be?

JH Jnr: Difficult question. I’m not sure there is one specific lesson that is more important than the rest. If you look at Dad’s central message, and you can apply this to what is happening in Eastern Europe today or to what’s happening in Northern Ireland, it is that difference is an accident of birth, plain and simple, and it therefore should be respected. If everyone has that as their central attitude towards life, then the world will get a lot better.

My Mum was, in many ways, fearless. Nothing fazed her at all, and that’s the way I will always remember her.

He was also a great believer in education, and education changed his life. He was one of the first generation of Northerners who got access to second and third-level education, and it was that generation that changed a lot. Education was very important to economic and social justice, and respect for difference. That’s really what they both stood for.

DM: Can you tell me a bit about the John and Pat Hume Foundation?

JH Jnr: The foundation is still very much in its infancy. It was founded after Dad passed away. It was Seán Farren, who was a colleague of Dad’s in the SDLP, and Tim Attwood who took the reins and have really done a fantastic job. They’ve built a board, which is composed of a unique group of people – they’re from north and south, east and west, they represent all traditions, and this foundation will be 100% apolitical.

Its job will be to keep that central philosophy of what Mum and Dad stood for and applying that not just to Ireland, but wherever in the world. The reality is that what Dad stood for – respect for difference, economic and social justice – the principles that he held close and what he espoused, you can apply them anywhere, and they are, unfortunately, still required, and people need to be reminded of them.

About the author: David Monaghan is Deputy Editor of Business & Finance.

About the author: David Monaghan is Deputy Editor of Business & Finance.