There’s a line in a lot of movies where someone says: ‘You know what, there’s things bigger than both of us.’ Twelve-and-a-half years ago, in a rather more optimistic time, I was at Westminster to hear the former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, make an historic speech to the joint Houses of Parliament, during which he stressed his commitment to a plural and inclusive future for the island of Ireland. As he put it that day, Ireland’s hour has come: A time of peace and prosperity of the old values and new beginnings.

A dozen years later having witnessed the depth of the divisions uncovered by Brexit, I find myself confronted on a daily basis by the reality that all values and new opportunities are not natural bedfellows. And the squaring that particular circle rook raised a lot of difficult questions, and from time to time requires us to make some extremely tough choices.

By way of example, as you’ve just heard, my present role at Westminster involves chairing a parliamentary select committee looking at the relationship between digital technologies and democracy – How can the former be encouraged to support, rather than undermine the latter? How do those old values sometimes incongruously incorporated in today’s form of representative democracy align with the enabling opportunities offered by our new digital world.

Now this is a conundrum being faced by free societies everywhere, and in the present we seem long on questions and somewhat short on answers. I think at the core of our bewilderment lies the issue of trust the golden mean that at least offers one degree of certainty in our lives as we’ve all discovered trust is hard to win but incredibly easy to lose. And it’s surely something more than just a nice to have I spent my adult life as a filmmaker and an educator so allow if I may to tell a story that I think combines the two: Several years ago I was asked to open a brand new school in the Northeast of England. There was emphasis then on building schools for the future that policy intended to deliver. As I walked through the impressive glass atrium to cut the ribbon, I looked up and in letters of fire were the words, ‘If it’s not true, don’t say it. If it’s not right, don’t do it’ – Marcus Aurelius.

The principal saw me gazing at it and said, ‘oh, that’s our school motto, we take that very seriously here.’ On the train back to London I couldn’t get the image out of my head. I kept thinking how is it possible that we have struggled so hard to conform to a simple rubric handed down by a Roman politician over two-and-a-half thousand years ago. It’s not as though it’s a particularly complicated thought. Now I’m no Pollyanna, but when a number of years later I first heard it suggested that we’ve moved into a post-truth era, I was genuinely horrified. Truth and trust being two sides of exactly the same coin, it’s difficult to see how we can help young people address the challenges of the 21st century without a thorough re-examination of what it really means to trust one another.

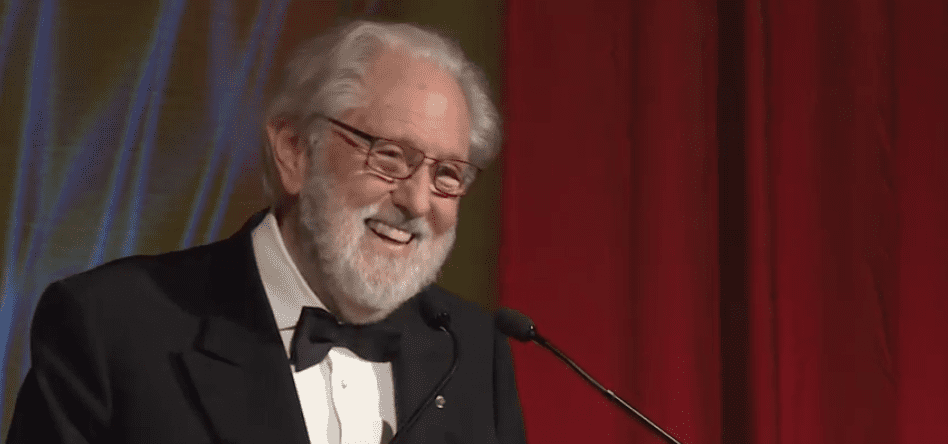

Because in truth I see the emergence of very few solutions but an ever-increasing number of seemingly insurmountable questions – all the more reason why we in Ireland have to seek our own place in the world and I’m entirely convinced that we will. Lastly I need to explain why in addition to receiving this honour, this particular week is of special importance to myself and my family: Exactly 30 years ago we arrived to celebrate our first Christmas in West Cork. 60 years ago tomorrow, I walked my then-girlfriend home from the school dance and asked her to go steady with me. A great joy of my life being that she still is with me here this evening.

And finally, as Enda [Kenny] very generously said, here today in Dublin, we finalised our citizenship application so you understand that when I say thank you, this evening is in every respect a very very important one in our lives thank, you very much indeed.